Argentina and the Limits of Fiscal Space

"Anything we can actually do, we can afford" is an important and underrated insight. The corrollary is that acting as if you "can afford" what you cannot "actually do" leads to trouble.

Javier Milei claims that he got into politics because his dead dog told him to, and now relies on that dog’s five clones for “advice”. He campaigned for the Argentine presidency with a chainsaw, wants to abandon the peso for the U.S. dollar, and believes Argentines should be able to sell their organs.

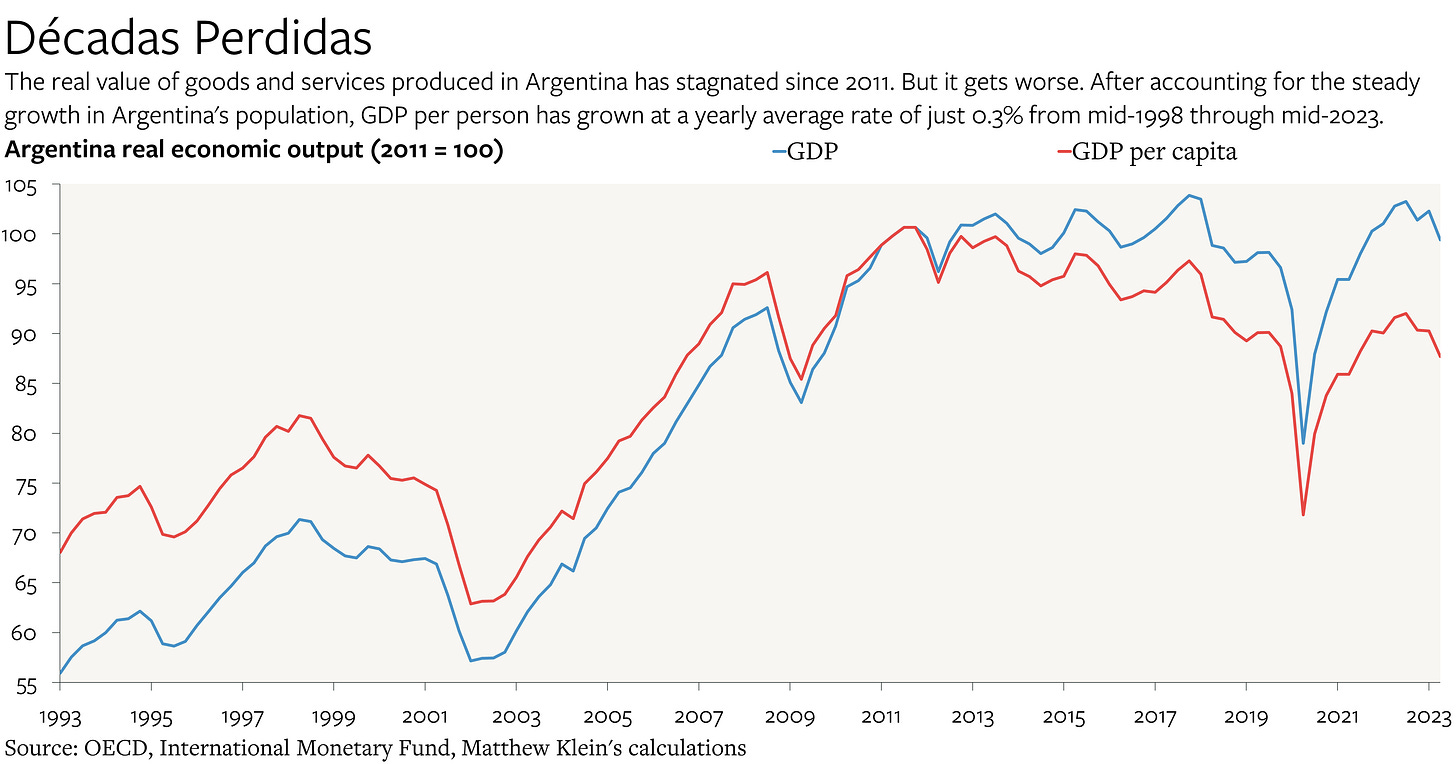

Yet Milei has just been inaugurated after winning by a large margin. Voters were willing to overlook his eccentricities because they were (rightly) desperate for change. Living standards are barely higher than they were 25 years ago, and are down significantly from the peak in 2011. The Argentine peso has depreciated roughly 99% against the U.S. dollar since 2016 and yearly inflation is in the triple-digits. About 40% of Argentines live below the poverty line, with 10% of Argentines counted as being too poor to afford the “basic basket” of food. The child poverty rate is almost 60%.

Argentina has many longstanding problems, but the immediate issue is straightforward: nobody wants to keep money in Argentina.

Since the middle of 2018, Argentines have moved about $78 billion out of the country in cash, while foreign investors have sold $23 billion of Argentine bonds. Those flows have been mostly—but not fully—offset by the liquidation of Argentina’s foreign reserves, the largest-ever loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and a swapline from the People’s Bank of China.

That is not sustainable. The resolution will likely involve debt writedowns, exchange rate depreciation, and severe budgetary tightening.

Whether Milei can do that is beyond the scope of this note. (One challenge is that he has few allies in the Argentine legislature.) But understanding what is happening is important, not only for the 47 million people who live in Argentina, but for everyone else who wants to avoid a similar fate.

The rest of this note is divided into two main sections. The first is a detailed analysis of the balance sheet of the Argentine central bank (BCRA), and the second looks at the general macro problem afflicting Argentina.

The Failure of Financial Repression

Officially, the Argentine government does not borrow much relative to the size of the economy. The consolidated primary budget deficit of the central and provincial governments has come in under 2% of GDP for the past few years. Even after accounting for interest costs, the yearly deficit of around 4% of GDP (about US$20-$25 billion each year in 2018, 2019, 2021, and 2022) is not obviously too high relative to economic conditions.

But this picture is misleading.

The problem is that the BCRA has been buying Argentine government bonds hand over fist. According to the weekly balance sheet data, the BCRA increased its holdings of government securities by $67 billion between June 7, 2022 and November 30, 2023 (latest available)—with $26 billion of those purchases taking place in just the past two months! For perspective, Argentina’s GDP in 2023 is probably around $500 billion at the current official exchange rate.

In other words, this is not just a case of the central bank monetizing the budget deficit. The scale of purchases is far too large for that. Instead, the BCRA is monetizing the budget deficit and also trying to compensate for capital flight. Argentines have been dumping their holdings of government assets, leaving the central bank as the only buyer available. Whereas historically the BCRA mostly held “nontransferable bills and notes from the national treasury”, the recent buying has consisted almost entirely of “other government securities”.

The most obvious reason why Argentine government bonds are unattractive is that most of them are denominated in U.S. dollars and other hard currencies. While the BCRA does not provide a breakdown in its weekly balance sheet, the monthly numbers imply that 70%-80% of its claims on the Argentine government have been denominated in hard currency since early 2018. Despite the massive risks—the Argentine government most recently defaulted in May, 2020—the BCRA has almost always marked these bonds at face value. The notable exception was in 2018-2019, but the accounting methodology has since reverted.1

The BCRA has financed these purchases in three ways, all of which are unsustainable: