Settling Into 4% Inflation?

The data on income growth, labor churn, and credit flows are all consistent with a "new normal" where trend inflation is slightly faster than before the pandemic.

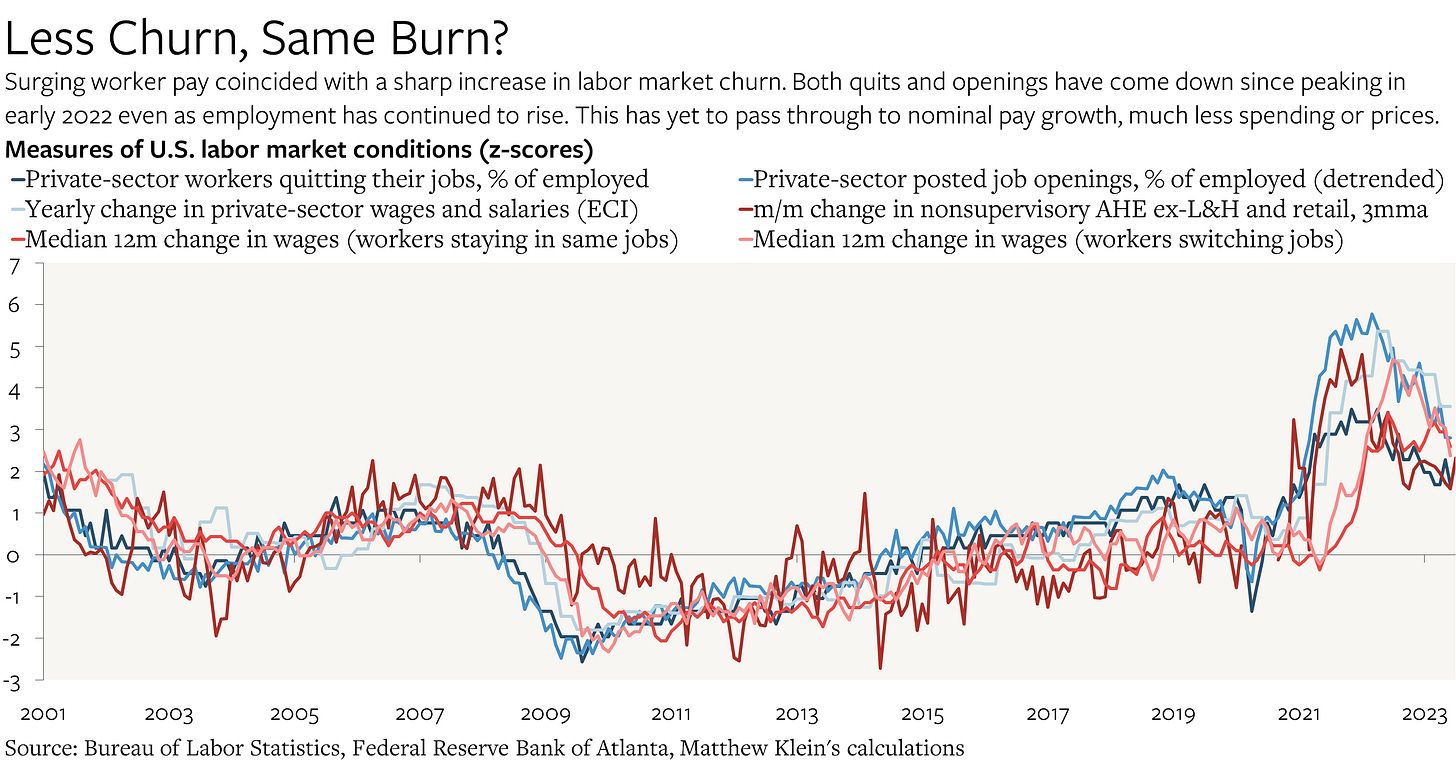

A year ago, I argued that the apparent acceleration in nominal wage growth looked like the result of large one-time shifts in the level of wages driven by a temporary spike in job market churn. At the time, my hope was that the ongoing decline in churn—a welcome consequence of post-pandemic normalization—would lead to a painless slowdown in (nominal) wage increases, ending inflation with zero costs for workers.

Apparently I jinxed it.

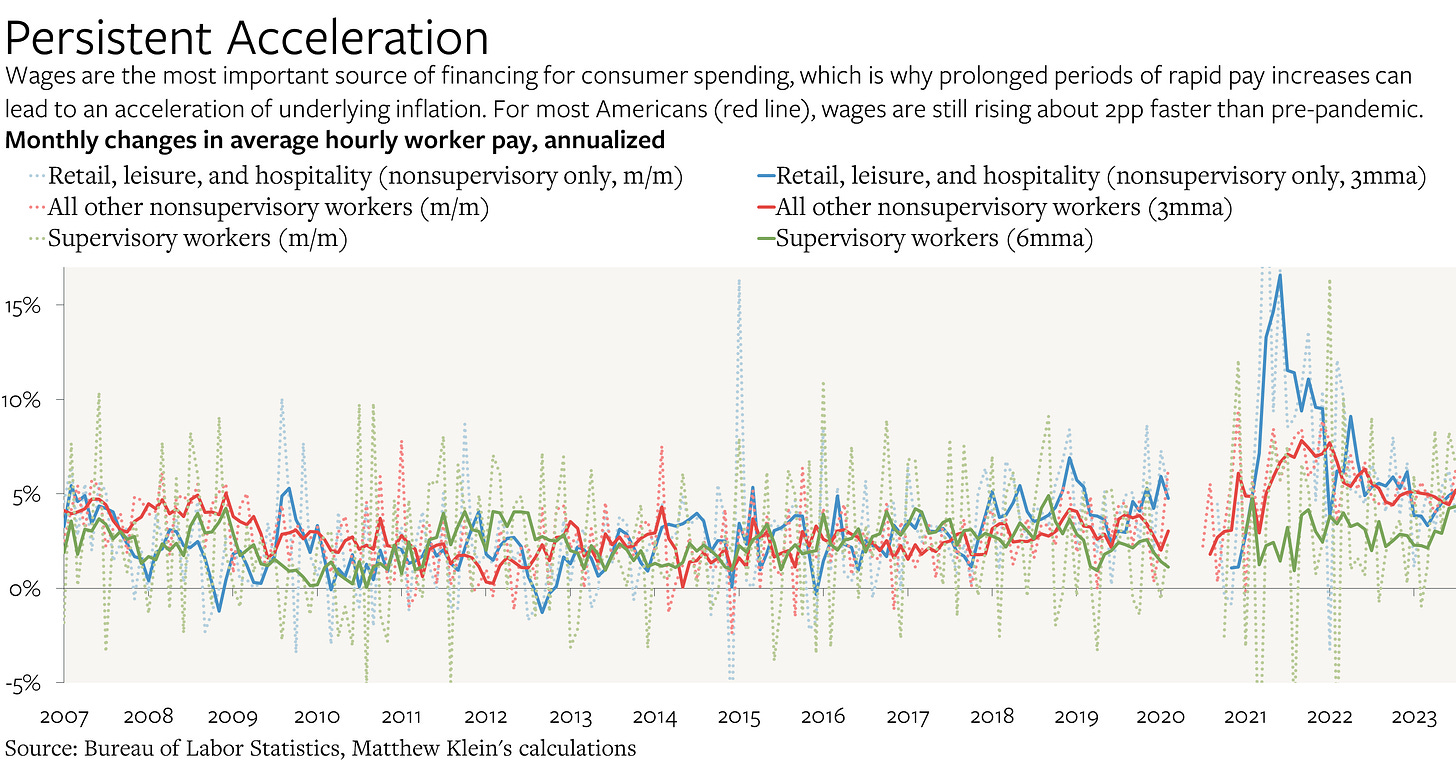

Ever since I wrote that note, the data have shown job churn coming down, yet nominal wage growth has remained stubbornly stuck around 5% a year. The latest numbers from this week are consistent with this surprising outcome.

Given the rough historical link between wages, output, and prices, the implication is that the trend growth rate of nominal gross domestic product (GDP) is now around 5-6% a year while trend inflation is around 4% a year. As I put it last August:

The growth rates of wages (or prices) can accelerate or decelerate by a percentage point or two without a commensurate change in the growth rate of prices (or wages), but it’s difficult to imagine a massive sustained gap between the growth rates of the two measures.

This is far from a crisis. If anything, it would represent a successful policy reset informed by the arguments of many leading economists in the 2010s. But it is different enough from what people are used to—and might reasonably have expected—to create some potential issues for asset prices.