The Bank of England's Jonathan Haskel on Inflation, Productivity, Brexit, and More

An exclusive interview with a member of the Monetary Policy Committee.

On Friday, I interviewed Jonathan Haskel, an external member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC). We discussed the Bank’s latest Monetary Policy Report, the unique challenges faced by the U.K. economy—due in no small part to the British decision to leave the European Union—and why fixing the National Health Service might help ease inflationary pressures. What follows is an edited and annotated transcript of our conversation.

Matthew Klein: The Bank’s target is 2% inflation. Inflation has run much faster than that in the past two years, but the Bank projects that inflation will run substantially slower than the target starting in 2024—even excluding energy. The Bank is also projecting that real GDP and real post-tax labor income will be lower at the end of 2025 than it had been on the eve of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, with unemployment rising.

The stated justification is that “the risks to inflation are skewed significantly to the upside.” You have repeatedly voted for larger interest rate increases than the majority of your colleagues and have said that you are particularly worried about “inflation persistence” relative to the baseline forecast based on your read of the job market. Can you elaborate on that and explain why you are expecting to keep monetary policy relatively tight for so long despite the baseline projection of below-target inflation and rising slack?

Jonathan Haskel: We in Britain are caught in this terrible bind of having a U.S.-style tight labor market with a European-style tight energy market. What I mean by that is the British labor market is very tight, with a very high increase in the vacancy to unemployment ratio, for example, which is a standard measure of tightness. We have a big increase in the number of people who are inactive—the fall in the number of people who are active in the labor market, which is quite a British thing. And then on the energy side, we’ve got this colossal increase in natural gas prices. U.S. spot gas prices 3-4 years ago were around €20 per megawatt hour. British ones and the European ones were about the same, but in the summer of 2022, they reached €250 per megawatt hour.

So what does all that mean? We’ve got this forecast which has got very negative effects. Inflation falls below target and we’ve got low GDP. So how do we think through all of this? The way I like to think about it is the following. We’ve got an enormous amount of uncertainty in the forecast. Of course, every central banker, when they start using the word “uncertainty,” you know that some sort of horrible excuse is just about to come along.

I’ve had the privilege to be on the MPC since September 2018. That has been a period of Brexit, a worldwide pandemic, and now a war in Europe. These are once-in-50-year occurrences, and I’ve had three of them in the four years that I’ve had the honor to be on the committee. So I think there’s a very elevated level of uncertainty around. What does one do? Does one throw out one’s hand and say “it’s all too difficult”, or does one say to the general population, “it’s all too hard and, you know, don’t blame us”? I wouldn’t, actually. I think economic theory tells you what to do.

There are two elements. First: if you’ve got sort of Knightian uncertainty, then that pushes you towards a robust control approach, which is to say what you want to be really, really careful about is the worst outcomes, like a very embedded inflationary momentum, which would then carry on with putting inflation above target. Second: if you’ve got all this uncertainty around, then you want to learn as much as you possibly can as the months go by, which will lower that uncertainty and reveal something.

So I discount the medium-term forecast more than I would otherwise, because there’s so much uncertainty.

And therefore, what I would prefer to do is make policy with much more attention on the data flow over the next few months, giving me the possibility of learning whether these Knightan uncertainties are going to materialize or not.

Matthew Klein: Is “this is what we're publishing, but we are worried about the uncertainty and want to learn as we go” the consensus view of the MPC? Is that why it seems odd to outside observers who just focus on the headline projections?

Jonathan Haskel: I don't think I've heard my colleagues put it quite in the way that I've described, although my colleague Dave Ramsden has talked a lot about these robust control issues. What we do in the forecast is we produce a modal forecast and a mean forecast. I don’t know whether other agencies do this, but what we do is we put together the modal forecast and then we put a skew on the forecast if we think there are particular risks. My interpretation of the published edition of the forecast, which comes under the heading of the best collective judgment of the committee, is that, because we think these risks are skewed to the upside with that skew in the medium term, we’re not gonna have this big plunge that you see in the modal forecast. I shouldn't really speak on behalf of what other people on the committee think, but I think it's fair to say that most of us are super focused on, as I say, what the evolving data is, and in particular the data in this very tight labor market that we've got.

Matthew Klein: The labor market is tight by a lot of measures that you mentioned, and yet real wages have fallen substantially. And in fact, the forecast is showing that real post-tax labor income is going to stay down for years.

Obviously nominal worker pay is rising rapidly, but how do we reconcile that with broader claims about the state of the job market?

Jonathan Haskel: As a number of us on the committee have said, what we have suffered in the UK is a big negative terms of trade shock. The stuff we are buying has become more expensive and the stuff we are selling has not become more expensive. That means that on a level basis, and Olivier Blanchard has written about this on Twitter, there is a terrible distributional issue in terms of our consumption behavior.

Somebody’s got to take that hit as long as we want to keep buying all this stuff from foreign producers.

Returns to labor or returns to capital have got to go down. You are right, real wages have indeed gone down. That is an unfortunate byproduct of the horrible economic logic that somebody’s real returns have got to fall.

Our research, and we had a little tweet thread on this recently, suggests that returns to capital haven’t really changed very much. So the burden seems to have fallen thus far on labor.

I think that makes sense from an economic principles point of view. Relative to the U.S., I think of us as being a small open economy with a pretty open capital market. So to a first approximation, our return on capital is going to be kind of pinned down by the global return on capital. There’s probably not that much squeezing one can do of returns to capital in an open economy with mobile capital.

Matthew Klein: So two things follow from this. One is: to what extent can we think about the ostensible labor market tightness in the U.K. having translated to the distribution of that hit so far, where, as you said, there hasn’t really been an impact on returns to capital? And then the other question is: the Bank has the job of stabilizing inflation, and you’ve also said that the way we stabilize inflation is basically a function of this distributional conflict among foreign energy exporters, every foreign producer of everything that’s not energy, domestic labor, and domestic capital, so implicitly the Bank has some role in mediating that conflict. How do you see that playing out?

Jonathan Haskel: Two really interesting questions, Matt. As far as the tight labor market is concerned, the returns to labor and the returns to capital are of course relative to some kind of counterfactual. And what we don’t know is: if the labor market had been loose, would the distribution of these returns have been different?

There’s this old literature, you know, going back to Bruno and Sachs under the heading of “real wage resistance”, which is the extent to which these external shocks—they were concerned with oil shocks at the time—are distributed between labor and capital. In that literature, the role of the tight labor market was expressed in terms of the time it took for the income hit to work its way through to the people who primarily sell labor and the people who primarily own capital.

What we’ve seen in the U.K. is a very U.S.-style labor market in the last 40-odd years. Mrs. Thatcher’s deregulation—getting rid of unions in a very similar way to the U.S., etc. Normally we think of the U.K. as having that small-l liberal labor market with a quick adjustment to external shocks. I guess what the tightness has done is put some sand in the wheels of that adjustment. Quite how that adjustment is gonna work out depends upon whether the sort of enduring labor market enduring real wage resistance or not.

I think I should say—because I think it’s correct—that the Bank has no role in this. Where the distributional hit lands is a matter of what the market outcome is. If, ex post, societies want to then start playing around with the tax system and all that kind of thing to redistribute and so forth, that is a political decision for them.

What the Bank is about is making sure that over that process of adjustment, we don’t get locked into these ruinous second-round effects where wages chase prices and prices chase wages and so forth. That I think is the Bank’s role: nothing direct, on the distributional side, but more on trying to prevent the inflation.

Matthew Klein: I want to push back on that a little bit. Suppose that the government says “we are going to shield households from the impact of an energy price hit,” which it has. In the Monetary Policy Report, the Bank says that the short term inflation impact is going to be down, because the consumer prices are going to be depressed by the energy price cap, but the medium-term impact on inflation is that it will go up because there will be more spending power for everything else. So how much flexibility is there actually to cushion this distributional effect, if the relevant fiscal measures themselves potentially have an impact on the longer-term inflation outlook in the way that was described in the Monetary Policy Report?

Jonathan Haskel: Yeah, I see what you mean. If the government defends—for understandable reasons—the population against the real income hit, that means that consumption is higher than it would otherwise be. And hence, demand is higher than it would otherwise be. And that’s a spillover towards higher inflation than would otherwise be the case.

What that goes to is a question about how good our forecast is about incorporating those various feedback loops.

We forecast consumption and the main GDP aggregates. What we don’t have—but we are trying to develop—are these heterogeneous agent models where you’ve got high income people and low income people, and the high income people have got different marginal propensities to consume.

And so the distribution of the energy price cap, for example, is really going to matter for the various outcomes. And then there might be feed feedback loops that low consumption means low activity and that feeds back into even lower consumption. We don’t currently do very much of that, although we do have internal models that take account of consumption at different points on the income distribution. In the forecast we would hopefully pick some of those effects up.

Matthew Klein: You mentioned earlier that because the U.K. is a small open economy, there isn’t a lot that can be done to make capital bear the brunt of the losses from the energy terms of trade shock, so that in practice the impact will get felt almost entirely by some combination of U.K. consumers and producers of non-energy goods in the rest of the world. It sounds as if that constraint is true regardless of whether governments try to use the fiscal system. Maybe some individuals can be protected, but the more you do that, the more you support total consumption—and therefore the less you actually solve the underlying inflation issue. Is that a fair way of characterizing the dilemma? How would you think about that?

Jonathan Haskel: In a sense, this is the tyranny of the national income identity. The, the size of GDP is the rewards to capital and the rewards to labor. Real GDP in consumption terms is the size of GDP divided by the price of consumption. The price of consumption depends upon what any economy does domestically, but also the slice of consumption that comes from foreigners, in this case energy. So I think it’s just inescapable that domestic agents have got to take a hit. No matter how we defend different groups, ultimately that hit has got to be incident upon the price of labor or the price of capital.

Matthew Klein: Let’s do a little bit of cross-country comparison, because while the U.K. is very different from the U.S. or Canada in terms of this energy shock, it’s much closer to the experience of what you might have seen in Europe or Japan or Korea. Some of them are having similar inflation outcomes, but there’s a bit of a range there, especially in terms of the forecast for consumption growth. The way this is reconciled in the Monetary Policy Report is that U.K. potential GDP has been marked down about 4.5% over the past few years, which is a huge hit.

There are a couple reasons you list. One of them, which is very relevant to your research, is about business investment being weak. Now there is a line in the MPR that says that business investment is expected to remain weak over the forecast horizon “in the face of weaker demand and tighter financial conditions,” which is striking to me because the weaker demand and tighter financial conditions are in fact the deliberate results of the Bank’s current policy choices. How are you thinking about the tradeoff between managing the current cycle vs. the impact on longer-term potential?

Jonathan Haskel: Yes, we have downgraded our forecast of structural output growth. Around 2015-2018 we just decided that we had had ~2% productivity growth, pre-GFC and ~1% productivity growth post-GFC. Then there’s the vexed question of Brexit. More recently, the decline has been an hours effect, because of the rise in inactivity.

To your specific question, it is true that when we raise rates that is not good for investment. I absolutely accept that, and therefore we are potentially contributing to that very poor capital investment.

What I would hope is that we only have to raise rates for a small time relative to some equilibrium level, and so therefore it would be hopefully a small period of time over which investment would be held back.

Remember, the capital stock is absolutely ginormous, so if there were a few quarters where investment is lower than it would otherwise be, that thankfully is not going to make that much difference to the total size of the capital stock.

On the other hand, if we had to hold rates above some equilibrium r* level for years and years and years and years and years, that would indeed have the very serious consequence that you are saying. So I acknowledge that there is a negative effect there, but as I say, I would hope that that would only be a temporary thing whilst we try to get inflation under control.

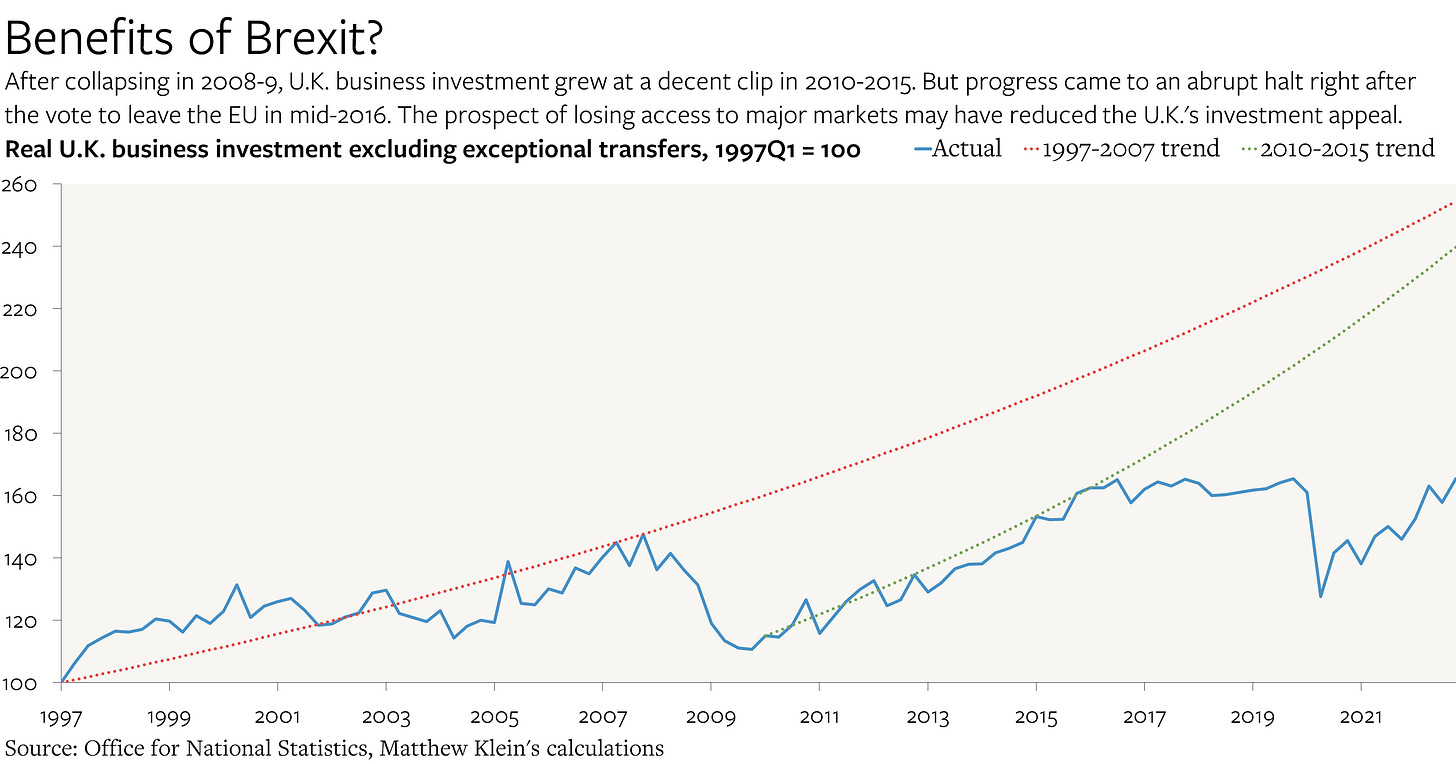

Matthew Klein: You mention, as you said, the “vexed question” of Brexit. Any outside observer can see the line of British business investment going up until you hit 2016 and then it flat-lines, which is very unusual relative to peer economies.

There are also data on trade that look similar. Have there been any studies about what the impact would be if the U.K. were hypothetically to rejoin the European Union, and what that would imply for sort of the longer term productivity outlook?

Jonathan Haskel: Let me try to answer that question directly and then say a bit more about Brexit. I don’t think there have been any studies of the U.K. rejoining. The studies are mostly inferring the cost of Brexit using gravity equations, which is to say one looks at the volume of trade between country A and country B controlling for relative GDPs and distance and stuff like that. What you notice is that when countries join trading blocs, trade goes up. There are very few examples of countries withdrawing from trading blocks. So those gravity studies of Brexit are all based on the negative of the positive effect of joining, if you see what I mean. It might well be that the impact of coming out of a trading bloc is different from the inverse of the positive effect of joining.

Now in the MPR chart 3.6 shows that the level of goods trade is around 10-15% below what we think it would otherwise be. We really don’t know what’s happening with services trade, although that would be confounded by the impact of the pandemic on travel and tourism. Step two of the argument is then to multiply that change in goods trade by some multiplier, which tells you what the decline in GDP is going to be based on an assumed relationship between trade and GDP. That gives you a level change predicted for Brexit of about 3.2% on GDP, which is what the Bank has been talking about. The Treasury has got a similar estimate. That is the productivity impact of the reduction in trade—a reduced-form estimate from the broad relationship between GDP and openness.

Let me tell you one more thing, if I may, which is not in the report, but is a little calculation that we have done about investment. Imagine that business investment hadn’t basically flattened out after the 2016 referendum and instead rose as real investment did in more or less every other country. What you could do is you could ask the computer to sort of simulate what would’ve happened to the capital stock, had investment carried on growing at the pre-referendum rate, and then figure out what the gap is between that simulated number and the actual number, which is a consequence of flat investment.

If you do all of that you find that the current productivity penalty is about 1.3% of GDP. That 1.3% of GDP is about £29 billion, or roughly £1000 per household. At the end of the forecast period, the penalty goes up to something like 2.8% of GDP, which is very close to the 3.2% number we found using the totally different reduced form methodology based on goods trade volumes.

Why is the British economy so weak on the supply side relative to both history and also relative to other countries? I think this says that Brexit seems like at least one important element of all of that.

Matthew Klein: You mentioned before that the weakness of U.K. productivity growth since the global financial crisis is very striking, particularly relative to the pre-crisis growth period and particularly when compared to other countries. One naive interpretation is that the 1997-2007 period was an anomaly. Alternatively, there actually were some real things that explain the post-GFC slowdown. Could you give a sense of what your research has found?

Jonathan Haskel: So what we’ve tried to do in the book with my friend and colleague Stian Westlake is look at the role of intangible investment in this whole story. First of all, we think intangible investment—I mean R&D, software, knowledge investment rather than very tangible things like buildings and vehicles and so forth—is of growing importance. That’s well documented. Think of the leading companies in the world: Apple, Microsoft, Google are all companies with giant intangible assets rather than tangible assets like an oil company or a car company might have. The second point about intangibles is that these investments probably throw off lots of spillovers. If you write a piece of open-source software code, I can use that code and that contributes to economy-wide productivity gains.

Since the financial crisis, there has been a slowdown in the pace of intangible investment—not so much in the U.S., but a bit in Europe and a bit in the U.K. And so that means with less intangible investment going on, that slows productivity, but it also slows these spillovers as well, potentially. And that would give you a decline in TFP [total factor productivity, the unexplained increase in real output/hour worked after accounting for observed increases in the capital stock and labor quality].

There also seem to be changes in the degree to which the benefits of those investments can spill over. If the spillover potential from intangible investment has gone down, that might be another reason why economy-wide productivity might slow down. One possibility is that the big firms—the Googles, the Microsofts, the Apples, and so forth—are just so good at using their intangible assets internally that the spillovers to other firms have just gone down. There’s just something about the synergies about having a team of AI people within Google and all that kind of thing. So I think that that that’s one possibility.

The other possibility that you mentioned is, and this is the Bob Gordon story, is that maybe the 1997-2007 acceleration, which was very concentrated in manufacturing in the U.K. was just very special. And maybe if that’s over, we are just back to lower productivity. The TFP slowdown in manufacturing alone explains around half of the total TFP slowdown since 2007. That is actually a lot of the total given the relative size of manufacturing in the U.K. economy.

After we finished the interview, Haskel sent me a revised version of a paper he wrote with Peter Goodrich that provides a more detailed breakdown (in Table 6 and Appendix F). U.K. economy-wide TFP growth in 2007-2019 was about 1.72pp slower than in 2000-2007. Of that slowdown, 0.77pp can be attributed to the U.K. manufacturing sector, particularly transport equipment, machinery, food/beverages/tobacco, pharmaceuticals, and computers and electronics. Another 0.72pp can be explained by the reported slowdown in TFP growth for financial services and insurance. For most of these sectors, productivity growth before the GFC was much faster than in the rest of the U.K. economy. For finance, much of that productivity growth was probably fake.

Since U.K. economy-wide output/hour (not the same as TFP) grew at the same average rate in 1997-2007 as in 1971-1996 even as manufacturing and financial services productivity growth accelerated, the implication must be that productivity growth in nonfinancial services must have already been slowing down in the 2000s.

Matthew Klein: Every country has had a productivity slowdown relative to the pre-2007 period. But the U.K. is an extreme outlier, and was an outlier even before the referendum to leave the EU. What do you make of that?

Jonathan Haskel: Yes, we suffered much more. A bit of that is that we have this larger financial sector. But I think it really goes back to Brexit. If you look in the period up to 2016, it’s true that we had a bigger slowdown in productivity up to 2016, but we had a lot of investment. We had a big boom between 2012-ish to 2016. But then investment just plateaued from 2016, and we dropped to the bottom of G7 countries. So I think if one were to start breaking up the slowdown and chopping it at 2016, that would be the basic story, which is we did have a bigger slowdown, but we were starting to recover somewhat, but then we were stymied again in 2016 for the reasons we were just talking about a little earlier on.

Matthew Klein: So in your view, the pre-2016 underperformance may be a bit due to finance, but is otherwise sort of a illusion?

Jonathan Haskel: And a cyclical thing, which we probably could have pushed that out a little bit and we’ve had all that extra booming investment. I say we were at the top of the wave, of investment in 2012. If we pushed that out a little bit, then our slowdown may not have looked quite so bad, but it was stopped in its tracks in 2016.

Lastly, we haven’t talked very much about inactivity. Inactivity behavior here looks very different to other countries: we’ve had a rise while other countries have had a fall. In the U.K., the inactivity rate for 15-64 year olds has increased by 0.8 percentage points between 2019Q4 and 2022Q3. The OECD average is minus 0.42 percentage points. The only other countries where the inactivity rate has increased by more than the U.K. are Columbia (3.2pp), Chile (1.7pp), Switzerland (1.4pp), and Iceland (1pp). My little team and I here at the Bank have tried to do some work where we look at the correlates of all of this, because the obvious question is: is there something going on about ill health?

There are basically two competing hypotheses here in the U.K. One is that actually lots of people have just retired. They were not active before and they’ve decided to give it up and just retire. Um, that’s hypothesis one. Hypothesis two is, is related to ill health. The National Health Service here has had very long waiting lists. It’s proved to be very, very difficult for a very overstretched health service to deal with Covid and deal with the aftermath. We are finding some weak correlations between regional increases in inactivity and regional increases in self-reported ill health within the U.K.

So we think there’s something going on with the health story, and one part of that story might be a sort of spillover story, which is “my partner becomes sick and can’t get treatment, is afraid of a further infection and so my partner withdraws from the labor force, but then I have to go and look after them, although I’m healthy.” So the effects of ill health as it were magnified via those effects. I think that’s another part of the kind of “why Britain?” along with Brexit.

Matthew Klein: Thank you very much for your time!