The Chicago Fed's Austan Goolsbee on Inflation, the Stance of Monetary Policy, the "Field Guide to R-Star", Managing Supply Shocks, and More

An exclusive interview with the president of Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, who will be a voting member of the FOMC in 2025.

On November 19 I interviewed Austan Goolsbee, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and a voting member of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) in 2025. We discussed the outlook for the U.S. economy, how he thinks about monetary policymaking, whether the neutral rate has moved, and what central bankers have learned over the past few years. What follows is an edited and annotated transcript of our conversation.

MCK: The Fed’s official view is that the inflation rate over the longer run is determined by monetary policy, primarily. Can you just talk me through how you think that works and how long the longer run is? What do you think are the things that determine inflation and how the Fed and monetary policy affects those things? What are the steps that you and your colleagues take to actually hit the targets?

Austan Goolsbee: I think that there’s a traditional environment and then there’s the COVID times, which don’t look like the normal environment. I think that in a normal demand-driven business cycle environment with a, let’s call it a stable Phillips curve, and we’re moving along in the short run with a kind of a tradeoff, I think of monetary policy in a way to be tip of the spear on macro stabilization.

The thing that’s made that much harder to figure out at this exact period, starting before I got to the Fed, but also while I’ve been at the Fed, is I don’t think it was a stable Phillips curve. This translates back into the arguments about was it supply or was it demand and a lot of the “it was stimulus that made inflation, it was excess demand that made inflation, predominantly” arguments are loosely in the category of, well, that’s what would happen if you had a stable environment and you had too much demand.

And I do think there was for sure some component of it where there was this extraordinarily stimulative episode in the United States, fiscal and monetary, but if you have that view that most of what happened with inflation was too much stimulus, you have two things you have to think about. One is: why, in a bunch of countries where they did not have as big of a stimulus on the fiscal side than what they had in the U.S., did they have very similar experiences with inflation? Second, why did inflation begin to soar here in the U.S. when the unemployment rate was literally 6%, which is not supposed to happen? That strongly suggests something is going wrong on the supply side of the economy.

MCK: Let’s imagine the general situation. In the normal times, you’re saying you are the tip of the spear in the stable—

Austan Goolsbee: In the normal times, the most interest rate sensitive sectors of the economy are also the most cyclically sensitive parts of the economy. For me, the primary channels of monetary policy transmission are through the real economy channels, like consumer durables, housing, business fixed investment, and to a lesser extent the dollar FX channel effect on exports and imports. And I’ve historically been less—I’m not disputing that the wealth effect channel has an impact. I think it does. It’s just that I’ve always weighted that a little smaller than some others do.

I think that’s the mechanism by which, in the economic-stabilization-short-run, monetary policy affects the inflation rate. We get demand shocks, the economy seems to be overheating, and we crank up the rate. It slows down economic activity in these cyclically sensitive interest rate sensitive sectors. And usually that works because we can influence the very part of the economy that’s the most up and down part.

And then that’s what comes to the thing that’s weird about this experience: we had a recession that was not driven by cyclically sensitive industries, and now the recovery. If you thought there was overheating, it wasn’t in interest rate sensitive parts of the economy.

So now we’re trying to figure out how sensitive to rates is economic activity. And is it that at this moment rates are less impactful, like the elasticity is lower? Or is it just that the lag is longer? And there is some evidence on both of those.

The “stimulus did this” crowd does have a strong thing in their favor, which is that it does look like the pent-up savings are correlated with why monetary policy is not as immediately impactful, but that’s really just a delay. Once the money runs out, then presumably we’d be back in an environment where it'll be more interest rate sensitive. We’ve been trying to balance those things out.

I tend to go to the real side monetary policy transmission mechanisms. What I’m thinking about is more short-run in nature, as opposed to like the longer run. There’s not a tradeoff between inflation and unemployment in the long run, it’s just determined by what's the actual potential output growth of the of the economy.

MCK: If you manage the real side to keep it stable, then inflation will just stay more or less at whatever particular rate it has been?

Austan Goolsbee: I’ve come 180 degrees, not full circle. I’ve come a half circle on the question of the inflation target and whether it should be 2.0 percent. When they announced an official inflation target back in 2012, I was critical. You can go back. I was a little critical because I felt that it conveyed a false sense of precision. Central banks don’t control it down to the decimal place. To say 2.0%, it would take you, given the variability of the inflation series monthly, you would probably have to have 10, 20 years of monthly data to tell the difference between 2.2% and 2.0%. So why say that?

I still have that issue with the level of precision, but the fact that actual inflation almost went to double digits and inflation expectations did not really vary off of that long run 2% is important. To get 2% inflation on the PCE we think is 2.2% to 2.3% CPI. What are the market expectations of CPI inflation?

The fact that when actual inflation was 7%, 8%, 9% and the expectations of long run CPI inflation remained exactly 2.2% to 2.3%—that’s either the biggest coincidence in the history of price series, or else the inflation target served as exactly the anchor that its advocates always said it would be when they advocated it.

That’s when I came 180 degrees.

I think the 2 percent target was critically important and that is an anchor that pulls us back. If you’re doing the stabilization job, you want to be watching inflation expectations the entire time you’re doing it to see whether the world finds credible what you’re announcing about policy. I think that we should find comfort if the expectations aren’t moving, there is a thing that’s pulling us back to a reasonable target inflation rate.

MCK: To what extent do you think that stability in TIPS breakevens was because there was a belief that inflation dynamics were temporary because of supply-related things during COVID, or alternatively, confidence that whatever happened, Fed policy action would somehow bring inflation back?

Austan Goolsbee: I think some of both. It would be hard to say that it did not entail either. I haven’t seen the international evidence, but I’d be interested in the international evidence on the question of how much people thought it was going to be temporary. This played out over a year-and-a-half to two years. At the beginning, when I wasn’t there, inflation was actually soaring. The Fed had not raised rates at all and was saying that they thought it was going to be temporary. Expectations didn’t go up at that moment as it became clear that it wasn’t going away.

The counterfactual is: do you think expectations would have stayed where they were if the Fed had not announced, “no, no, the FOMC has changed its mind, and now we’re going to raise the rates quite a lot, including, you know, some 75 basis point increases. We’re going to raise it as much as basically it's ever been raised in a single year.” If they hadn’t done that, would expectations have been fine? That’s kind of the same question. It feels like it would not have been fine. To that extent, I do think the Fed’s public commitment mattered.

You probably saw the Romer and Romer paper of when have we ever succeeded in getting inflation down. They summarize the historical evidence that a big public credible commitment to getting inflation down is actually quite important to getting inflation down without blowing up the world.

MCK: How do you judge whether policy at any given point in time is restrictive or stimulative or neutral?

Austan Goolsbee: And people got mad at me for calling r-star “r-sasquatch”! I’m not objecting to the idea of there being an r-star. What I’m questioning is: how useful is the concept of r-star for real time decision making in monetary policy? There are only a couple of ways to get a sense of how restrictive they are.

One, you can make historical comparisons. Two, you could have a model that you plug in. But it’s important to recognize that if you do a model, you’re doing historical comparison, you’re just attributing some other factor—demographics, productivity, growth, whatever. You are implicitly saying, “I’m going to base what I think the neutral rate is on these long run factors”. That’s not helpful in the short run for answering whether we should raise or lower the rate right now?

The third is the “field practitioners guide”, which is, “hey, we don’t know, so let’s kind of feel our way out.” If you’re approaching something like neutral, something like a steady state, the most interest rate sensitive sectors of the economy are where you would go look. That’s the art, because the thing has been made more complicated for all the reasons we just talked about before.

Normally you’d be like, “okay, well, is this neutral or is this restrictive? Let’s go look at auto financing and the demand for autos because that’s usually very interest rate sensitive.”

Well, you can’t really do that because autos are doing better than what you would have expected for how much the interest rate went up, but only because they were so depressed there was a bunch of pent-up demand. That field guide to “what’s neutral?” says to check how it really looks. Does it feel like interest rate sensitive sectors are looking like they are in a steady state?

The last time the SEP came out, if you looked at the dot plot, there was disagreement of about 75-100 basis points about where things would stop, but virtually everyone could agree that r-star was well below where we are now, and therefore you could start cutting. And as you start getting closer to what might be r-star, it would be perfectly sensible to slow the pace of how fast you’re doing that because there’s a lag to monetary policy’s impact.

The field guide version of figuring out what is neutral and what is restrictive involves looking around and seeing how conditions are behaving. You can’t do that in a two-week time frame. It takes a little time, so slowing down probably makes sense in that kind of circumstance.

I still read the models of what they think is r-star and try to back out what were these long run forces that they are identifying.

If you go by the historical model, it shouldn’t be a surprise that you think r-star is still low, because the last 40 years have been a trend downward. I’m interested in that, but I don’t take it completely at face value.

I’m probably more inclined to be a “field guide to r-star” guy.

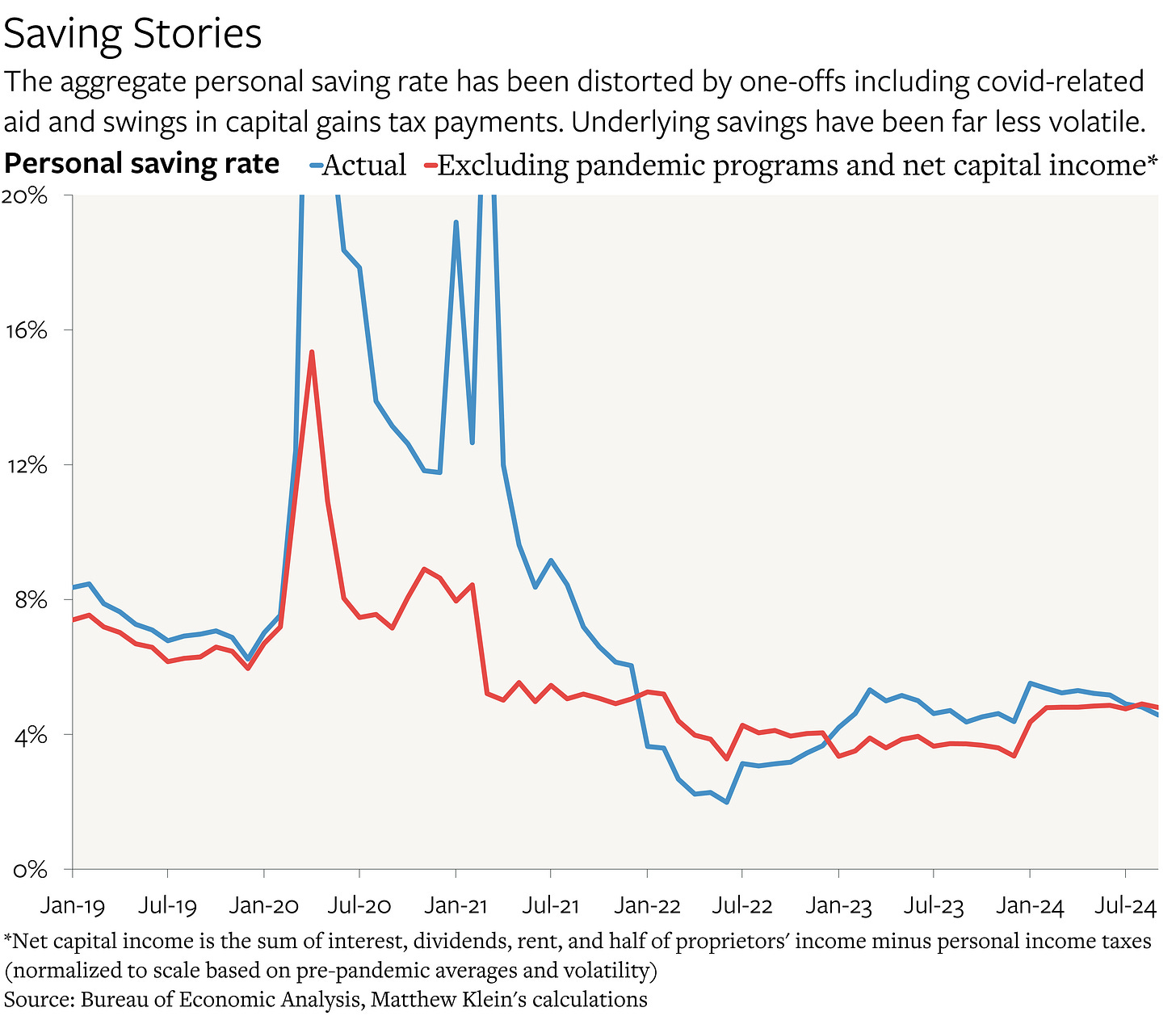

MCK: To your point before about this big accumulation of savings in the household sector and corporate sector, the savings rate is still high. It’s not as high as it was before the pandemic, but still, it’s not negative. Maybe there is reduced interest rate sensitivity of the economy now compared to five or six years ago. That could potentially change the perspective on where neutral would be in a way those models would not capture.

Austan Goolsbee: I agree with that. I should have said that one of the major dynamics on monetary policy transmission is the change in the mortgage market. Before the housing crisis, a majority or so of mortgages were adjustable-rate mortgages. And now the vast majority are 30-year fixed rate mortgages. That has made housing demand less immediately sensitive to the interest rate. It has also raised these much-discussed issues about supply, and is there “lock-in” and nobody wants to leave their house, etc. Those kinds of issues I do think lead us back to ones that affect r-star.

The one that I want to put out into the ether, and I’ve been saying it but maybe it’s so obvious that nobody is talking about it, but we’ve now had over a year of pretty tremendous productivity growth, faster than the previous trend. We have more than gotten back to the trend we were on before COVID. Many people said, “yes, we’re seeing rapid productivity growth, but it’s just getting us back to the previous trend. And then it’s going to stabilize and go back to what it was before.” It still might, it’s worth acknowledging.

But if the productivity growth rate goes up, if you just go work through the models, that affects what you think is neutral. If productivity growth is going to be permanently faster or faster than normal for a long while, that raises the neutral interest rate.

If it’s front loaded—that is to say, a temporary boom, where we had this one upward shock, and then it comes down—in most models that tends to reduce r-star in the short run. It’s worth thinking about this issue of whether the productivity growth rate is changing, that is directly changing what is potential output, and so that’s going to affect our decision about what’s neutral. In my world, which leans toward the “field operational guide to r-star,” that’s still fine. If you’re going straight off a model, that’s fitted to past data, that’s not really going to be fine. You’re going to have to think that through.

MCK: Interest rates, particularly the ones that affect a lot of the interest rate sensitive sectors that you mentioned, are not set at the short end. Given that the yield curve has been inverted for as long as it has—obviously it’s a very unusual situation—how do you think about where neutral would be given that longer-term rates have been more range bound and stable throughout this whole period?

Austan Goolsbee: Side note, in a different context, I’ve been saying, here are a bunch of indicators—the Sahm rule is a perfect example—all of those are just based on the past. We’re going to be a little flummoxed trying to figure out whether they apply now. So, for example, we violate the Sahm rule. Does that mean a recession is coming? Well, in the past it has, but there’s never been COVID. There never was a thing where the unemployment rate went like that, but labor force participation was as high as it was and the jobs numbers were still growing. [Note that Claudia Sahm agrees that her rule is not necessarily warning of a recession right now.]

Everybody said that the inverting yield curve was a sign of recession. Two years, the thing has been inverted. We didn’t have a recession. And I noted that now it’s un-inverting. Then they came out of the woodwork and said “You idiot, that’s the biggest sign of recession of all, when it was inverted and it becomes un-inverted. That’s when the recession begins!” Okay, look, maybe, I don’t know. But you have to admit that historical rules of thumb have not been giving much insight lately.

So long rates are going up. We started cutting the short rates, and then long rates start going up a bit. It matters why the long rates going up. And there are several potential explanations. One is the market could think inflation will go up. Subnote, if you’re in that category, then you have got to explain why when we measure inflation expectations, people do not anticipate that a big fraction of how much long rates went up are because they are expecting inflation to be higher.

Whenever we start looking at long rates, though, too, we have to also think about the reflection problem: are long rates rising because traders used to think we were going to cut short rates more than they do now? That makes me again want to look over a longer period than just the last four weeks. They’re up to what they were in the spring.

MCK: This is what I find interesting. You can look over the past two years and they’ve actually been relatively stable and rangebound, even as the short rate, as you know, went up and then it’s come back down a little. I’m wondering, from that perspective, how you think about where the short rate should be, given that long rates have been kind of range bound, but there’s also been an implicit pricing of short rates coming down.

Austan Goolsbee: You have to balance. There is some art to trying to figure out, what is the nature of the term premium? What is the nature of inflation expectations? I still think the inflation expectations measures are, to my mind, if not paramount, then they’re one of the most important measures in trying to tease out the explanations for why these rate moves are happening.

Some research of folks at the Chicago Fed kind of changed my thinking. I sit at the table next to [Minneapolis Fed president] Neel Kashkari, and he’s an old pal of mine. I knew him before I was ever at the Fed. He had a series of public musings that said “the real fed funds rate is as high as it’s been in decades, and as we’re making progress on inflation, the real fed funds rate is getting bigger and bigger.” And he said, “but look at 10-year Treasurys, they’re not up as much as the Fed Funds rate is up,” implying that maybe we’re not that restrictive.

So our folks went back and looked at previous rate hiking cycles. How much do long rates go up when short rates go up? And the answer is it’s not a one-for-one, it’s usually 25 percent. If short rates go up 100 basis points, long rates go up 25 basis points. And this time it actually was 50%, not 25%. It was more translated into long rates from short rates than in previous rate hiking cycles. Now, I realize at this exact moment, they’re going in opposite directions. So that is a kind of an instructive data point. But I think we should take the data in on long rates and on all financial conditions, but be a little wary of concluding lessons about monetary policy short run rates from what the level of those things are there.

I really want us to think carefully because of this reflection problem. Take the financial conditions measures. There are some people who say that financial conditions are loose. That is partly because of spreads, but it is mostly coming from equity markets—equities go up a lot and that immediately says financial conditions are loose. But let’s say that the market believes that the Fed is credible, and that we are going to hit what I’ve called the “golden path” with inflation going down to 2 percent without a recession. Then equity prices will go up and it will look like financial conditions are loosening. This logic would say that you better raise rates because financial conditions indices are so loose.

But if the looseness of the indices is because traders have concluded that we’re going to cut the rates and it’s going to work, then that would be the exact wrong logic. It’s circular. Doesn’t it feel like things are kind of normalizing? Like we’ve been in this totally strange environment for two years-plus, with an inverted yield curve and now long rates are going back to something like normal and short rates are coming back to something like normal and the yield curve is going regular. Isn’t that good news?

MCK: You mentioned the term premium. Do you think there’s a lingering impact of the asset purchases that were done in 2020 and 2021? Even though you’re still in the runoff phase, that there’s still so much on the balance sheet that it’s still having an impact?

Austan Goolsbee: First, let’s have a sidebar on the balance sheet. There are a lot of people who don’t follow it closely enough and don’t recognize that we’ve changed the way we do monetary policy. We have this ample reserves regime now. We’re never going to go back to a balance sheet that’s as small as it was when we were in the in the old regime.

My read of much of the evidence was that the expansion of the balance sheet did have an impact, but it wasn’t a giant impact on longer rates—more on mortgage-backed securities than on treasurys. You’ve seen the FOMC put out a statement that, over time, they’re trying to phase it to be more and more treasurys. In the short run, the supply and demand of treasurys does matter, but over the long run, I think that managing the balance sheet is just about maintaining ample reserves. We’re out of using that as an alternative form of monetary policy. That was more like a crisis instrument.

MCK: One of the traditional arguments for central bank independence is that voters and politicians have an inflation bias. It seems like that’s apparently not the case, based on the U.S. and other countries’ recent experience. What do you think are the implications, if any, for monetary policy if popular preferences regarding any kind of growth/inflation tradeoff are, in fact, potentially the opposite of what’s in a textbook model?

Austan Goolsbee: On the wider public hating inflation, you might have seen Jon Steinsson has written about this. I do think that in our basic models, if you want to think of it that way, the fact that people hate inflation as much as they seem to have demonstrated they hate inflation should make everybody a little more cautious of things that risk generating inflation. You’d want to be a little more circumspect about it, and that would affect monetary policy decisions.

To the extent you’re asking about fiscal policy, we’re not in the fiscal policy business. You know, those are just the conditions that we accept and if they affect inflation or employment then we run scenarios and we think about them, but we’re not weighing in whether this is a good fiscal policy or this is a bad one.

I still think that Fed independence on both theory grounds and empirical grounds is critically important. Go look at countries where the central bank is not independent. Here, Fed independence just means that in the technical sense, the sitting administration cannot tell the central bank what interest rate to set. In places where they can, inflation is much higher, expectations of inflation are much higher, and growth outcomes are worse. That’s why it’s virtually unanimous among economists that Fed independence is really important.

That’s not about bank regulation, where the primary presumption of Fed independence does not exist. That’s not about people who work at the Fed who previously worked in an administration, or people in an administration who previously worked at the Fed. It’s whether the sitting administration can set interest rates.

I tend to think of it less that they have a taste for inflation, but that monetary policy’s impact on inflation comes with a lag. If they have a higher discount rate, then they’re going to be prone to take actions in the short run to emphasize one side of the mandate that have a longer run negative impact and raise inflation expectations, but that will be a problem to come in the future.

For our monetary policy decision making, we should take into account that people really look like they hate inflation. Though, back up and remember the post 2008 period people hate high unemployment, too. Maybe the emphasis is you better do a good job because if you start getting off the path on either side, people are going to be upset at you. But to the extent that we just rediscovered around the world that people hate inflation even more than what we thought, we should put that into our loss function.

MCK: Thinking about how people respond to inflation, how do you think the Fed should respond to supply shocks, whether they come from external things like COVID or potentially policy-related ones that might be coming down the pipeline? What do you think is the right way to manage that given this kind of extreme distaste for inflation?

Austan Goolsbee: Then we splice on the extreme distaste for inflation. Let me hold that one to the side, because it’s hard enough to figure out how do you respond to supply shocks. You have to figure out whether these are temporary supply shocks or permanent supply shocks. That matters a lot. And you have to figure out, is this a one-time cost increase but a temporary inflation shock, or is this something that’s going to keep spiraling and gets flooded into expectations?

The conventional wisdom, I would say before this episode, was you don’t tighten into a supply shock, but you try to prevent the secondary impacts on inflation. The direct impact of higher oil prices, there’s nothing you can do about that. You’re going to get inflation from it. But you try to prevent wage-price spiraling, you try to prevent it from getting folded into expectations where you can’t get rid of it. That’s still probably right. In a way we can’t yet update conventional wisdom for this episode until it’s done and we’ve actually figured out how much was supply and how much was demand.

I came from a from a point of view thinking that it was mostly supply shocks but I will say we’ve learned a new thing that we also need to pay attention to is how persistent the spillovers are. If “team transitory” had described themselves as “team supply shock” from the beginning, it would have spared us a lot of angst.

I do think one thing we learned was the supply chain is so many stages now that when chips were not there, then the computers that use those chips had their prices go up, and then when the computers’ price went up, then the autos that use those little computers, their price went up. Then the FedEx driver who’s using the car—it had a “if you give a mouse a cookie” element to it.

We should think about that when we’re thinking about monetary policy reaction to supply shocks. It leads us back to the present moment. If we’re getting positive supply shocks, either productivity growth, or immigration, or the supply chain healing, how long will that benefit continue? We had a big increase in labor force participation. It stopped improving, but it remains at a high level. Will that work its way through over a long period just the same way it did when it went wrong? I think maybe, yes, but that’s partly what makes the pattern recognition on the monetary policy side a little more complicated.

MCK: Thank you very much for your time!