Americans' Incomes Are Rising Too Fast for 2% Inflation

The question is whether that is enough of a problem to justify the costs of addressing it.

The average American’s disposable income has been rising 10% a year since last summer thanks to falling tax payments (down 9% from the peak in September due to lower capital gains obligations), huge increases in Social Security benefits (up 9% in January thanks to backward-looking cost of living adjustments), and—most importantly—soaring employment income.

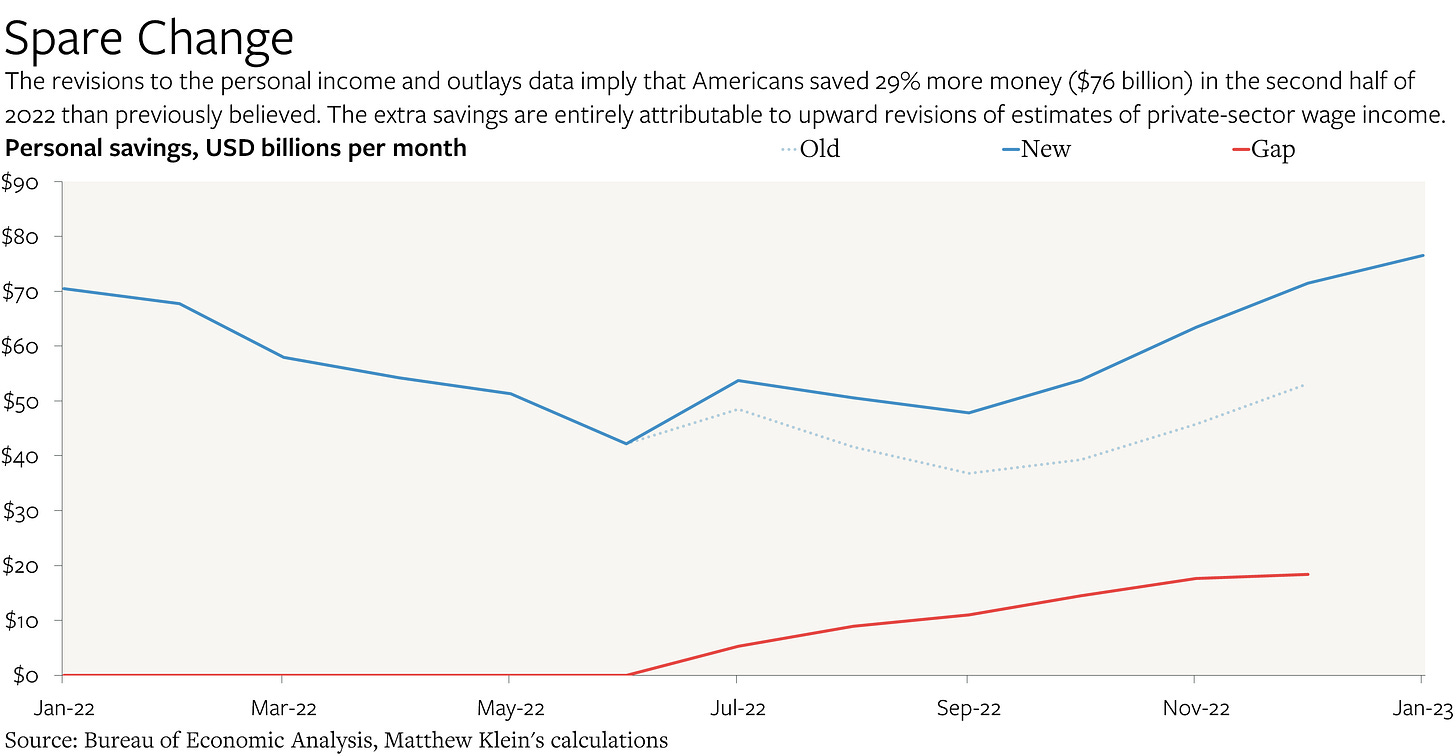

The good news is that this income surge should continue to finance additional consumer spending while protecting most households’ balance sheets. In fact, revised estimates from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) now imply that Americans saved1 an extra $76 billion (29%) in the second half of 2022 because wage income for private-sector workers in July-December was $70 billion (1.5%) higher than previously believed.

The problem is what this means for inflation. If the personal saving rate has been stable, rather than falling, it increases the likelihood that additional earnings will translate directly into additional consumption. And unless businesses increase their production of goods and services in line with the extra spending, prices will have to keep rising to make up the difference.2

The latest inflation data support this thesis, with no signs of disinflation since last summer—particularly in the categories most sensitive to domestic economic conditions and discretionary demand. On the bright side, a good chunk of the 10% annualized nominal income growth seems to be tied to real output and to quirks of how revisions are incorporated into the data, although the implied underlying rate of inflation is still around 4-5% a year.

Behind the Boom in Employment Income

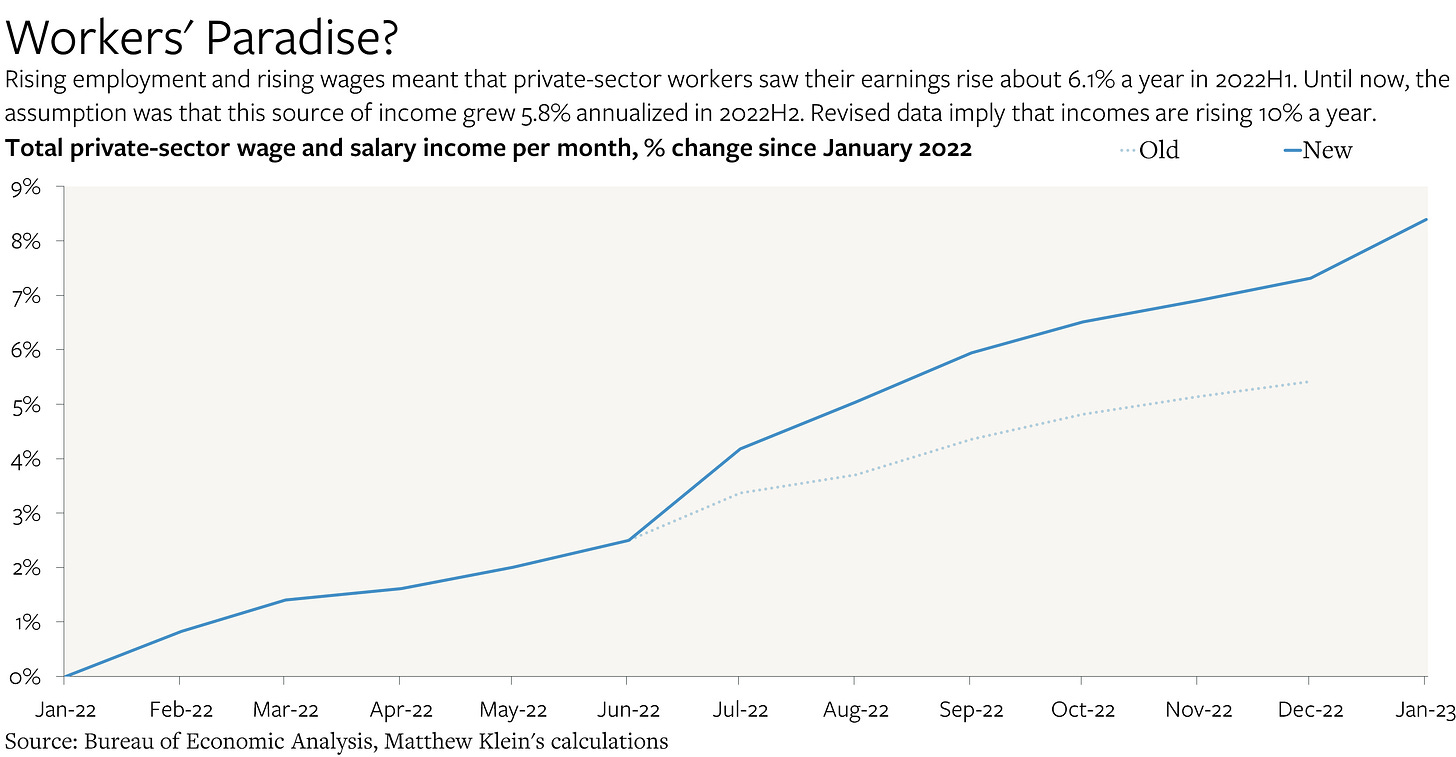

Worker pay matters for inflation because it is the largest and least volatile source of financing for consumer spending. The old data implied that wages and salaries paid to private sector workers were rising about 6% a year throughout 2022. The new data imply that wage and salary income has been rising 10% annualized since June.

But this mostly seems to reflect upward revisions to estimates of the number of people working (and the length of their workweeks), rather than how much each worker is getting paid. That should mute the potential impact on inflation—assuming the extra employees are doing useful things with their time.