Are America's "Excess" Savings Here to Stay?

U.S. consumers saved trillions via lower spending and generous government aid. So far, they have yet to go on a spending binge to make up for lost time or to counteract the impact of rising prices.

The pandemic led to an unprecedented collapse in consumer spending, an unprecedented surge in business borrowing to cover lost revenues, and an unprecedented flood of government spending and loan guarantees across much of the world.

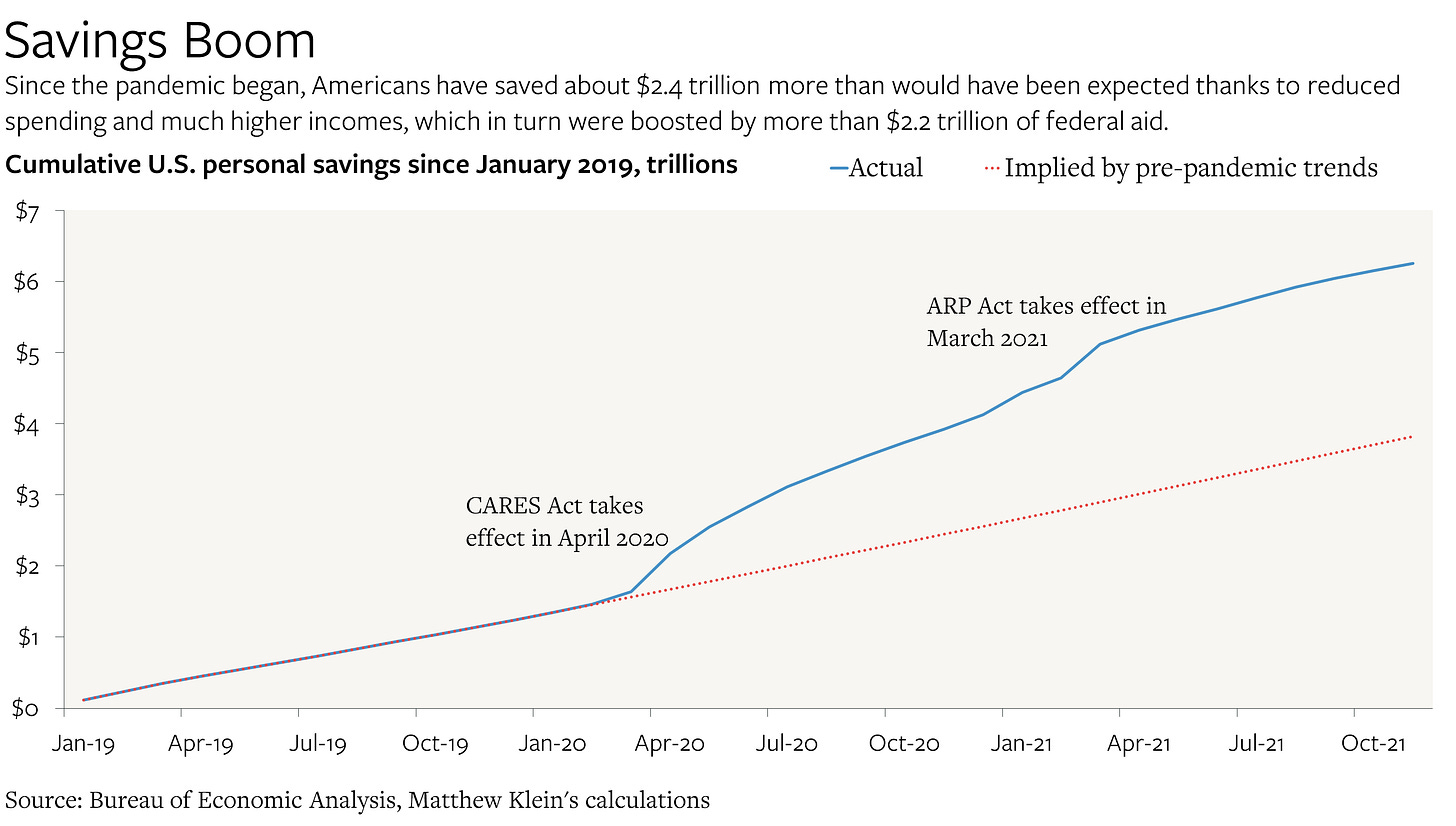

The net effect was that household savings ballooned, with holdings of physical currency, bank deposits, money-market fund shares, and similar instruments soaring by trillions of dollars in the U.S., Europe, Japan, and the other rich countries. Relative to what would have been expected based on pre-pandemic trends, American households have about $2.4 trillion in “excess” savings.

The question is: what’s going to happen to all that money?

Will the “excess” cash get spent in an orgy of “revenge consumption” as people make up for lost time? If so, how much of the extra spending will go towards additional goods and services as opposed to higher prices? Maybe the “excess” will instead get squeezed out of precarious consumers as emergency income supports and other forms of government aid are withdrawn to facilitate budgetary tightening.

Perhaps the entire idea of a latent cash hoard is an illusion because some Americans plowed more money into housing and their brokerage accounts while others paid down their credit card balances. After all, the official definition of “saving” is basically just income minus spending on consumer goods, services, and interest payments,1 which leaves a lot of room for other uses.

Or maybe the pandemic-era savings boom will leave a permanent mark on household balance sheets, with most of the extra cash sitting relatively inert in untouched deposits that indirectly finance the government debt issued in response to the pandemic in the first place.

The closest historical analogy we have—the post-WWII experience—suggests that the last option may be the most likely, although there are enough differences between now and then for me to be wary about making the case too strongly. So instead, I’m going to focus on what exactly has happened so far, what’s changing, and where we might end up as 2022 unfolds.

I’m also going to split this note up into two parts. The first will focus on the income and consumption numbers, while the second will look at financial transactions and balance sheets.