China's Depression and the U.S. Inflation Outlook

Underlying price pressures in 2024 were either the same or barely changed from 2023. That was despite a worsening slowdown in China that reduced demand for commodities and manufactured goods.

I recently published a column at Politico on the potential pitfalls with using tariffs to support American reindustrialization. Check it out!

The last mile is the hardest after all.

U.S. inflation was about 8% a year in 2021H2-2022H11, up from less than 2% a year immediately before the pandemic. By December 2024, the U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) was up just 2.9% over the previous year, while the 12-month change in the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) price index preferred by Federal Reserve officials is likely going to come in around 2.5%. This improvement occurred without any meaningful slowdown in spending, much less the kind of job market downturn that some feared would be necessary.

But there is less to this than meets the eye, and inflation remains about 1 percentage point faster than before the pandemic at a yearly rate. Worse, there are reasons to think that the relatively benign conditions of the past few years could reverse even without any disruptive policy changes in the U.S. In particular, if Chinese policymakers succeed in getting their economy out of its funk, American policymakers could face a serious challenge in bringing inflation back to target.

How We Got Here

Most of the extra inflation in the U.S. and other rich countries was effectively a policy choice to minimize the financial and economic damage from temporary disruptions to production, distribution, and consumer preferences caused by the pandemic and, to a lesser extent, Russia’s war on Ukraine. Unsurprisingly, the inflationary impulse from the one-off policy response dissipated as conditions normalized. As early as 2022H2, inflation had already slowed to ~3% annualized.2

The big question was always going to be: where would inflation settle once the crisis was over?

Many expected that the pre-pandemic world would return, with comparable rates of inflation, spending growth, and interest rates. Others thought that the pandemic and the policy response altered the fundamentals so much that the post-pandemic world would have to be meaningfully different from what came before. From this perspective, it was helpful to think of the 2020s as somewhat analogous to the 1940s. So far, the evidence seems to support this latter interpretation.

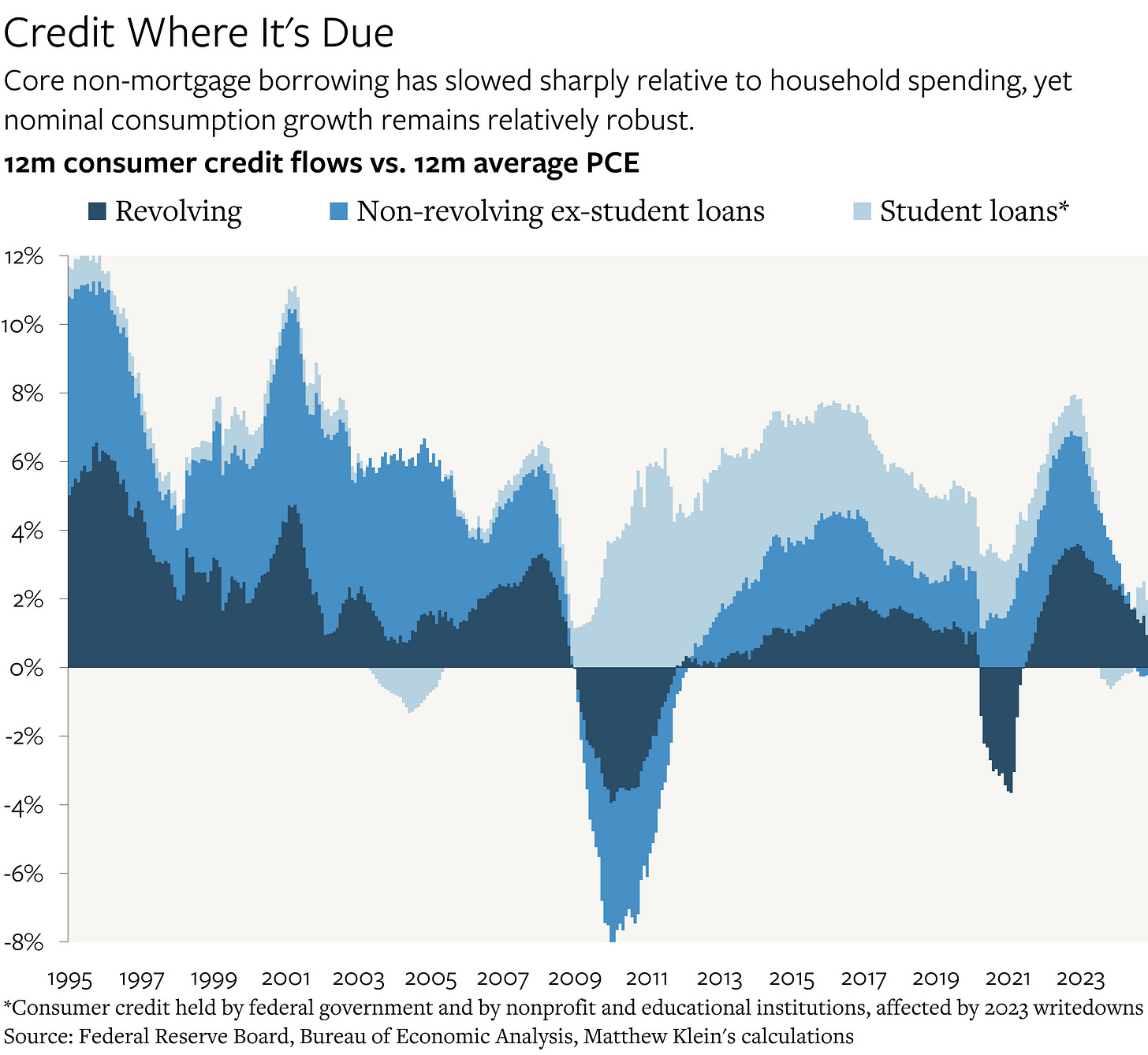

Household balance sheets that had been impaired ever since the financial crisis were suddenly infused with cash, allowing richer consumers to accumulate liquid assets as poorer ones stocked up on durables and housing without increasing their indebtedness.

Together, these factors made consumers less sensitive to changes in financial conditions than they were before. That in turn helps explain why higher interest rates did not hit the real economy as much as feared, as well as why inflation has remained faster than before the pandemic for far longer than many had expected. The flip side is that Americans’ massive untapped borrowing capacity could potentially be unleashed if interest rates fell enough.

With this context, the stability in many of the inflation numbers over the past couple of years makes more sense.