Doing My Part to Raise R*

Or: Some Personal News

Welcome new subscribers!

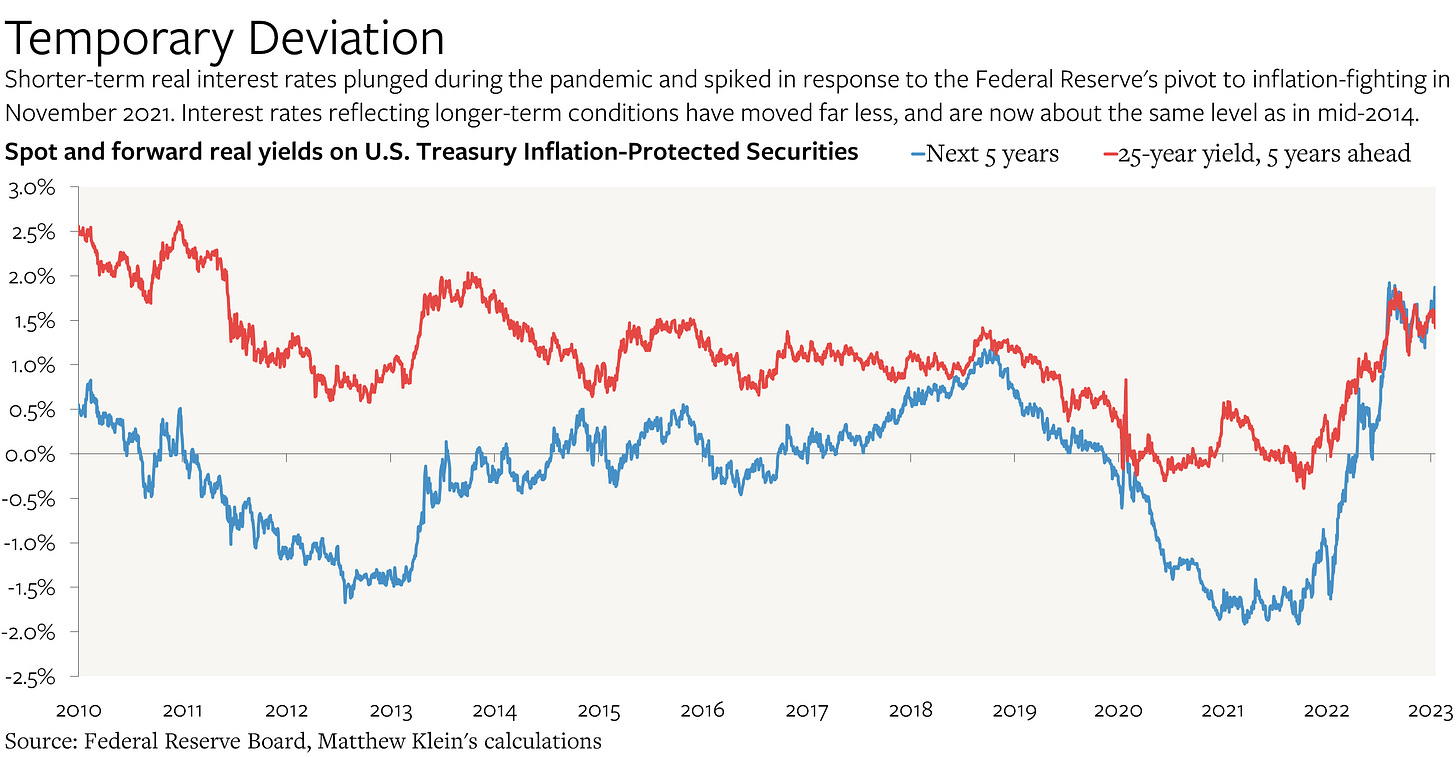

Until recently, the great problem vexing macroeconomists across much of the world was the fact that interest rates were so low.1 As I put it 18 months ago:

Interest rates are supposed to encourage or discourage spending according to each society’s needs at different points in time. If there is too much demand for goods and services relative to current production, high interest rates can potentially help by making it more expensive to borrow and by raising the rewards for those who abstain from spending.

But if nobody is consuming or investing, then it’s pointless to get people to spend even less. Thus inflation-adjusted interest rates tend to be higher when the economy is growing rapidly and lower (or negative) during downturns and periods of slow growth. From this perspective, the relentless decline in interest rates is a signal of serious social problems.

There are many potential complementary explanations, which I discussed in detail in that note. (I believe that the increase in income concentration is the single most important factor.) But Adrien Auclert, Hannes Malmberg, Frédéric Martenet, and Matthew Rognlie identified another significant social challenge that has likely contributed to the longer-term drop in interest rates: population growth has slowed sharply thanks to a plunge in the number of children being born in the major economies.2

Fewer children means less growth and less need to invest in the future. That should depress the “neutral” short-term interest rate (R*) that is supposed to balance saving and spending and keep the economy on an even keel. Kevin Ferry joked in response to my earlier note that the mantra should be: “have a baby, buy a bond, save the world.”

So I am happy to report that my wife and I—mostly her, let’s be honest—are doing our part, having recently returned from the hospital with our second child. (I wrote this in advance.) I am incredibly excited to introduce our new daughter to all the wonderful things the world has to offer, starting with her big sister and our cat.

For those who don’t know—or don’t remember—what newborns are like, they are born with relatively tiny stomachs, which means that the only way for them to get enough nutrition in the first ~6 weeks is if they eat every 2-3 hours. In between meals they need burping and invariably need at least one diaper change. Taking care of someone who does not let you sleep for more than 90 minutes at a time (at most) is incredibly rewarding, but it does inhibit the kind of deep research that makes my work possible. On top of which, we still have to make sure to keep everyone else fed, clean, and happy (including ourselves). We are fortunate to be able to have some help, but I will need to step away from The Overshoot for a short while.

Subscribers to UN/BALANCED should enjoy uninterrupted service (we pre-recorded a bit) while subscribers to The Overshoot will benefit from some excellent guest pieces I have commissioned.

What Does This Mean for You?

When I had my first child, I was fortunate to work at Barron’s, which had an enlightened view of parental leave. Mothers and fathers were both eligible for 20 weeks of paid time to spend with newborns, and I at least was encouraged to take the full amount in one go. Back then, I wrote a column arguing that everyone should do this. In addition to being better for new fathers—I loved being able to spend that much time with my daughter and focus on helping out—it would also be better for women in the workplace:

My parental leave ultimately reduces the career cost of children for my female colleagues. If mothers take time off to raise children, women will continue to be permanently disadvantaged for spending long stretches out of the office while men get promoted and move up the ladder. In most rich countries, the gender wage gap is entirely a function of motherhood, with childless women earning the same as their male peers. Little wonder, then, that mothers hold full-time jobs at much lower rates than men in every major economy.

This is obviously bad for women, but it is also bad for men—and business. A comprehensive study of 21,980 companies from 91 countries by economists Marcus Noland, Tyler Moran, and Barbara Kotschwar found that “the presence of female executives is associated with unusually strong firm performance,” while the absence of women leads to lower returns.

However, to make this work, I also argued that fathers actually needed to use their full leave. The problem is that workaholic men undermine the value of the benefit for other parents by taking less time than they are allotted:

Offering leave that can be shared between two parents is better than maternity leave alone, but it too is insufficient. Many European countries let new parents divvy up their parental leave between them. But leave there is used mostly by mothers. Even in such progressive bastions as Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, barely 10% of fathers take any parental leave.

This suggests the answer is to mandate more time off for fathers.

Noland and his co-authors found that “paternity leave is strongly correlated with the female share of board seats” because “policies that allow child care needs to be met but do not place the burden of care explicitly on womenincrease the chances that women can build the business acumen and professional contacts necessary to qualify for a corporate board.” Pushing men to spend more time with their children would therefore help both men and women. This is a collective action problem that requires a collective solution.

If everyone takes time off, the career penalty for any individual worker disappears. Companies initially resisted giving workers eight-hour days, weekends, and holidays, but they eventually adapted. There is no reason they can’t also accommodate the needs of men and women having families.

I still agree with all of this, although I do not believe that I as an independent business can reasonably ask you—my customers and clients—to tolerate 5-6 months of interrupted service.

Therefore, I will be off from now until May 8, although I have commissioned several guest pieces that I will publish between now and then. Starting May 8 I will be back full time and publishing at my regular cadence.

Being an independent professional has been incredibly rewarding, and I work very hard to offer you premium analysis that is worth paying for. I am grateful for all of your support and I look forward to getting back into the thick of things in a few weeks.

China plus the “high-income countries” have consistently accounted for about 80% of world GDP, although the relative importance of individual countries has shifted over time.

I'll gladly remain a paying subscriber while you take your entire paternity leave. I wish you and your recently enlarged family all the best.

Congratulations! Take the time you need to care for your family. Also buy bonds and save the world please.