Europe's Imbalances in Pandemic and War

How the major components of the world's third-largest economy have evolved over the past few years, from Italy's investment boom to Germany's export underperformance and more.

Europe was the major economy hit hardest by the disruptions of the past few years. Beyond the aggregate impact, the shocks of the pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine have also had varied effects on the many countries within Europe, both directly and as a result of different policy choices made by national leaders. Sometimes, these divergences entrenched pre-existing differences. But in many cases, Europe’s internal dynamics have shifted in new and surprising ways. While the broader picture is still one of a society that lives below its collective means, these subtler changes are worth keeping an eye on.

Before the Pandemic: A Refresher on Europe’s Long Crisis

Most of Europe endured a lost decade in the years leading up to the pandemic. That, as I explained at length in Trade Wars Are Class Wars, was ultimately a consequence of changes within Germany that were in turn responses to the perceived challenges of reunification.

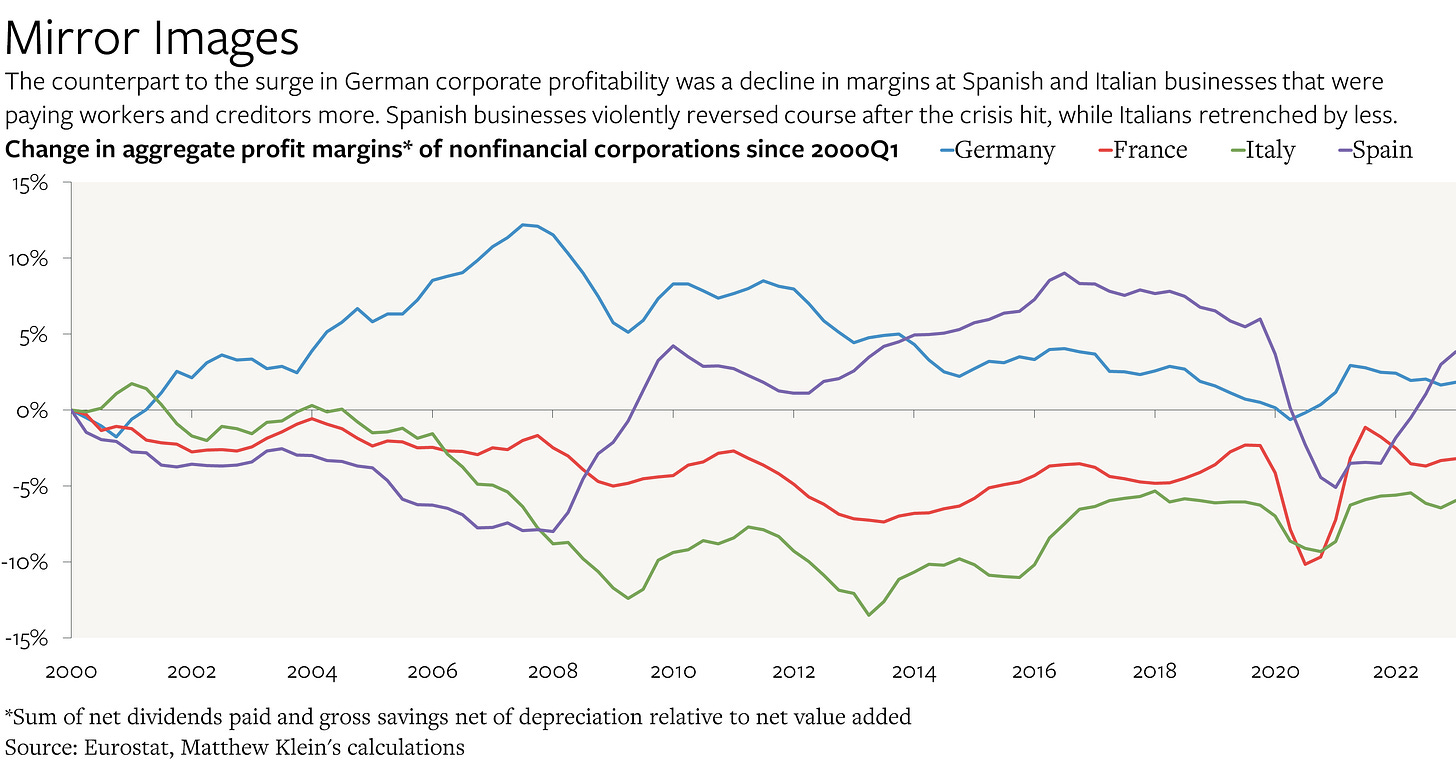

The short version is that German executives—including the proprietors of Germany’s many family-owned businesses—spent the early 2000s squeezing capital budgets, squeezing worker pay, repaying debts, and retaining earnings. Meanwhile, the German government decided that it could no longer afford a generous welfare state and decided to reinforce businesses’ earlier choices by pushing elderly jobless Germans into low-paying part-time work. The result was a “jobs miracle”, lower transfer spending, and higher tax revenue that did not correspond to actual worker output or living standards—even after the worker’s share normalized.

This was compounded by a separate decision to impose a constitutional borrowing limit on Germany’s federal government, states, and municipalities, which effectively capped investment spending and has left Germany with some of the worst infrastructure in Europe. (As well as an underequipped military.)

All of these changes depressed German spending. But German companies were still producing goods for global markets and generating sales from exports. That surplus was only possible because consumers and businesses in the rest of the world were able (and willing) to keep buying German goods even though the depression in Germany was limiting German demand for imported goods and services.

The corollary was that rich Germans and the companies they controlled were able to accumulate financial assets outside Germany precisely because they were providing financing to the rest of the world that enabled people outside Germany to spend more relative to their incomes than before. It is not a coincidence that the difference between the income earned in Germany and the money spent by Germans on goods, services, and construction rose as much as it did right as German companies began squeezing their own spending on pay and capex to boost profits and retained earnings.

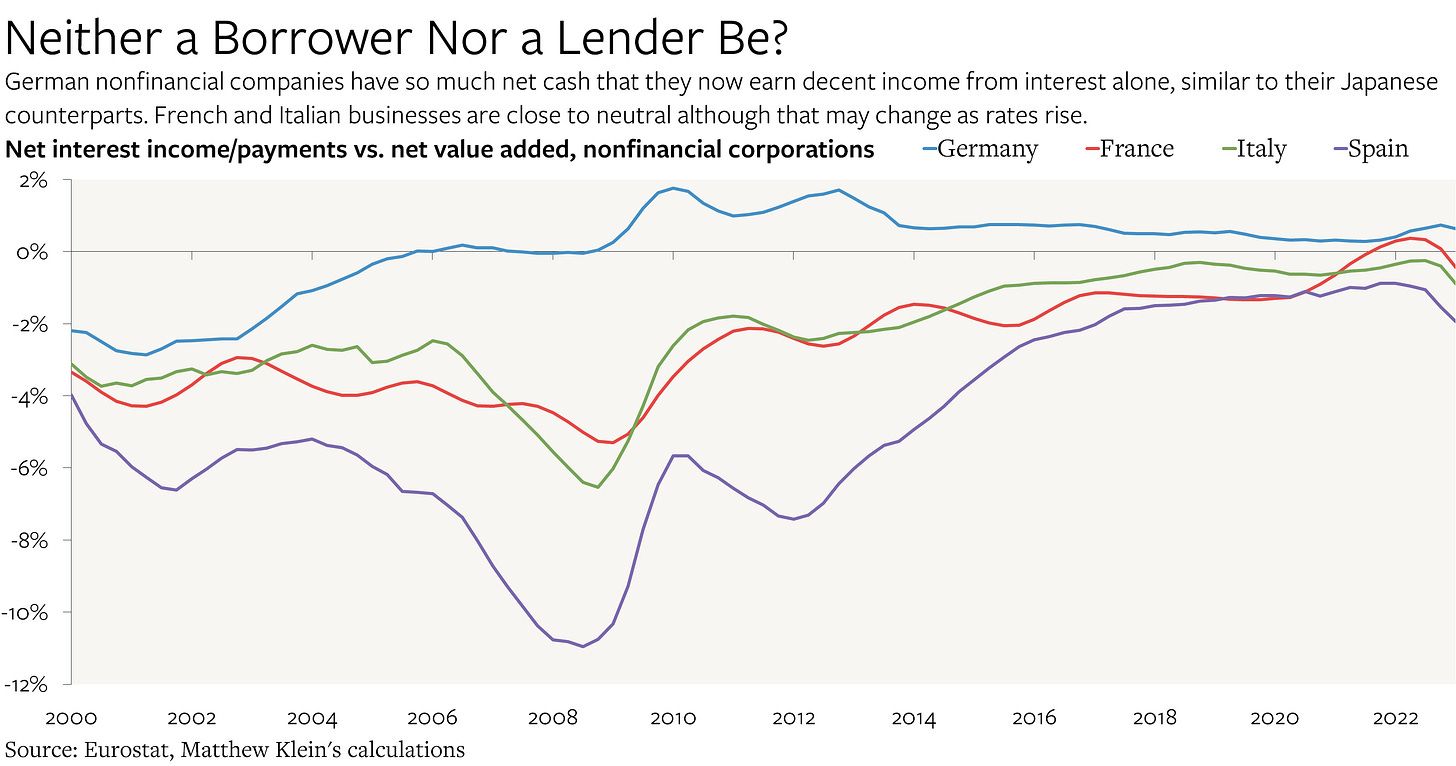

The shift was so extreme that German nonfinancial companies, like their Japanese counterparts, have consistently earned more interest income than they pay to creditors since 2009. Companies elsewhere in Europe have seen their net interest burden fall during the long period of zero-to-negative rates, but the situation in Germany is meaningfully different, especially because net interest income has been rising as rates go up.

Germany’s depression reduced global demand for goods and services compared to what it otherwise would have been. Everyone else had to endure some combination of higher debt (to offset the lost income from selling to Germans) or lower income. While the impact was distributed globally, the most obvious counterparts to Germany’s internal troubles were the country’s European neighbors.

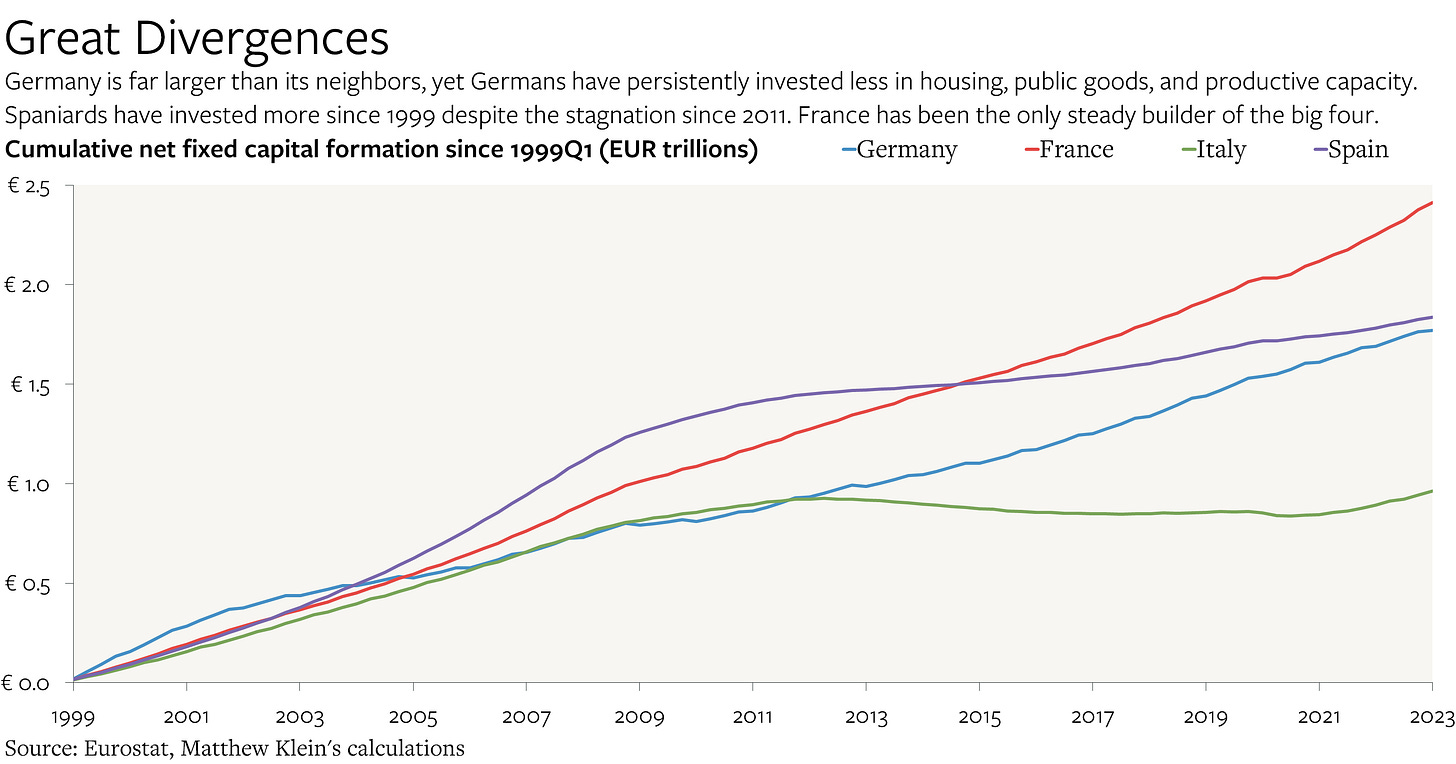

At the European aggregate level, Germany’s investment slump and stagnant consumption were offset by building booms in Spain, Greece, and central and eastern Europe. Since the beginning of 1999, there has been more investment in fixed capital (buildings, equipment, R&D, etc) net of depreciation in Spain than in Germany, even though Spain has only half of Germany’s population and has had almost no net investment since 2010. There was just as much net investment in Italy from 1999 through 2011 as in Germany—and Italy was far from booming in the 2000s, as well as far smaller.

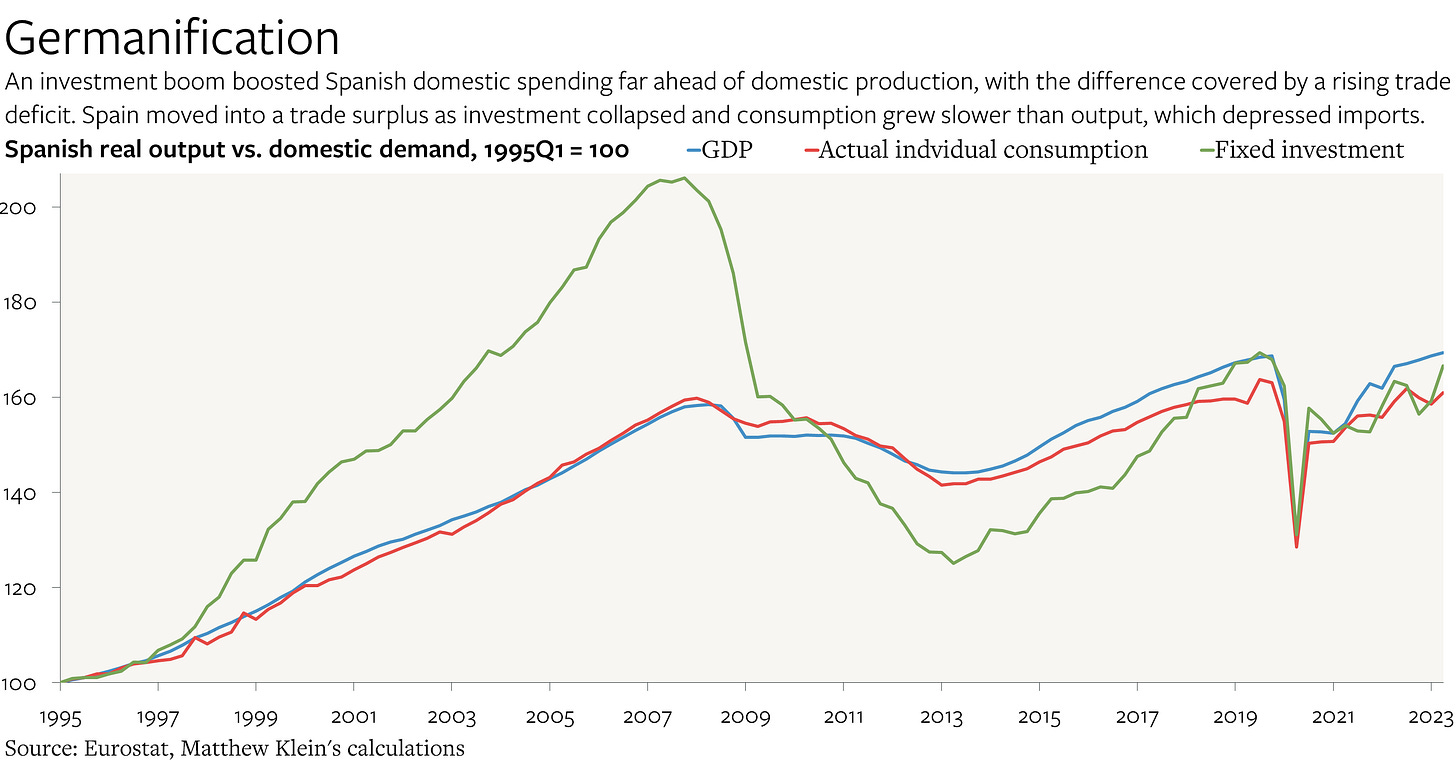

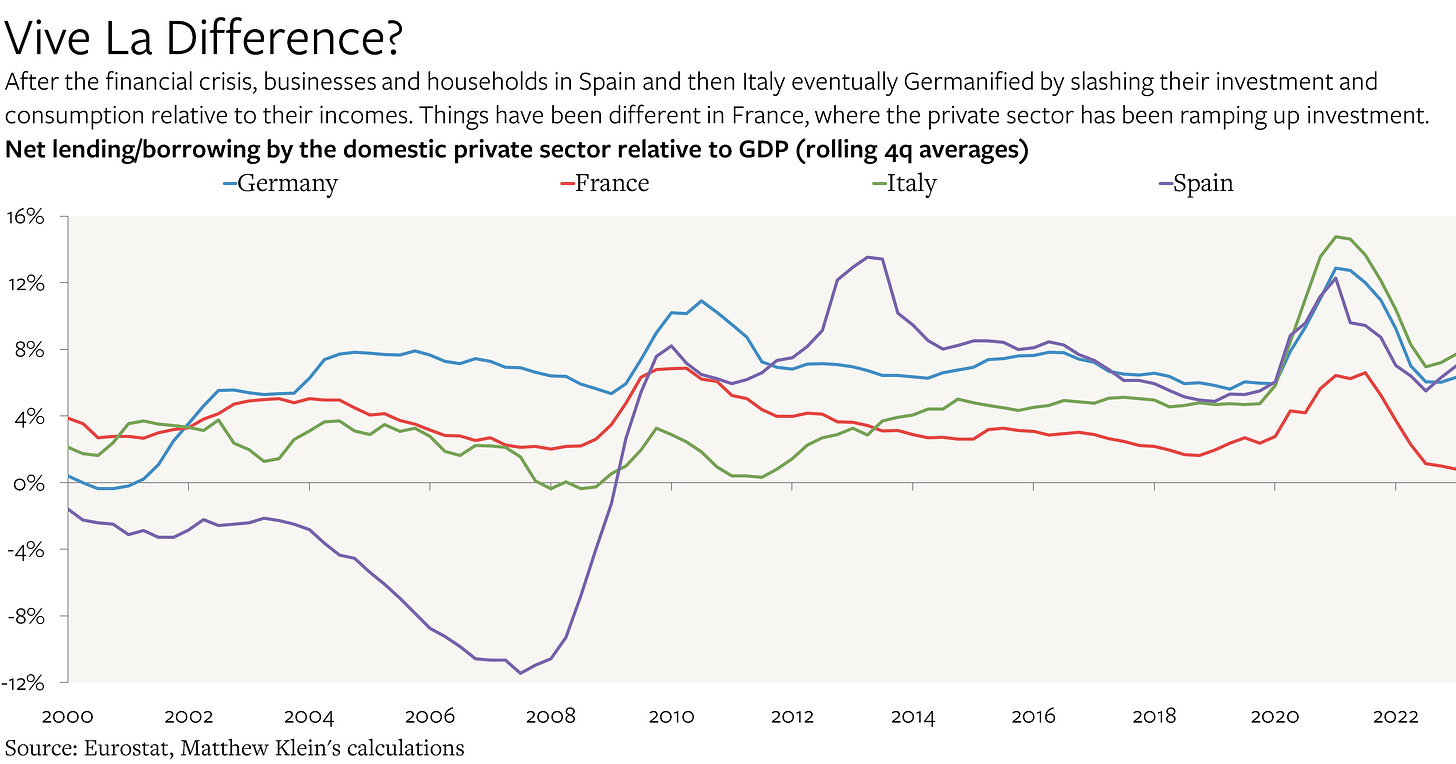

Spain’s investment boom ensured that Spaniards were going to be spending far more than they earned, which also corresponded to a surge in the trade deficit as imports rose far faster than exports. Spanish companies borrowed more, driving up their interest expense and depressing their profitability, and they also paid workers more, which further ate into margins and official estimates of productivity. Italian businesses did something somewhat similar, albeit at much smaller scale.

Eventually, the entire process violently reversed. Lenders had trouble finding new borrowers who were able (or willing) to take out more debt to finance ever-rising spending, while mounting losses on existing loans were reducing the appeal of further credit extensions. The result was a collapse in the places that had previously offset the global impact of Germany’s depression, without much of any change in Germany itself. Most of the rest of Europe was forced to “Germanize” economically, with all of the costs that entails. (It was essentially the European version of the EM crises of the early 1980s and later 1990s.)

The notable exception was France (and Belgium, which is much smaller). The French private sector felt relatively little pressure to adjust its behavior, while the government was also relatively free to run persistent (modest) budget deficits without slashing investment or welfare budgets.

By the eve of the pandemic, the result was that Europe as a whole was running the world’s largest trade surplus by a substantial margin. The flip side of this surplus was a severe decline in European living standards relative to domestic productive potential, as well as the diminished legitimacy of European democracy.

The Pandemic Hits

Given this context, one could easily have been pessimistic about Europe’s ability to manage both the public health crisis itself and the economic consequences of sheltering-in-place.

Was there enough goodwill left after years of bigoted recriminations and stereotyping? Could Europen officials mobilize enough financial support fast enough to prevent a Great Depression-level event? And even if they managed to do something, would it be nearly sufficient to meet the challenge? The European policymakers who imposed a lost decade (or worse) on hundreds of millions of their citizens in the 2010s—but also narrowly managed to avoid literally dissolving their single currency—have never lacked the capacity for self-congratulation.

But then, to her credit, Angela Merkel, Germany’s chancellor, decided that Europe as a whole needed to respond in size. While the European Union’s official Recovery and Resilience Facility was not particularly large relative to the needs of the moment, and was also too slow to disburse funds to be helpful for the immediate problem, the European Central Bank (ECB) made up for this by giving Europe’s national governments a relatively free hand to borrow.