Some Thoughts on U.S. International Economic Statecraft

The emerging consensus for greater government activism in domestic economic affairs should be paired with a more expansive vision of the constructive role that the U.S. can play internationally.

I recently had the chance to participate in a discussion with U.S. officials interested in the links between domestic economic priorities and international affairs. The discussion itself was off the record, but I thought it would be useful to write down and clarify my own views, as well as providing some of the context for my thinking.

I first got interested in understanding the links between the balance of payments and domestic economic conditions because I liked figuring out how lots of different moving parts fit together in a complex system. Only later did I come to appreciate the seriousness of the stakes.

Keynes knew better.1 Remember how he ended The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936):

War has several causes. Dictators and others such, to whom war offers, in expectation at least, a pleasurable excitement, find it easy to work on the natural bellicosity of their peoples. But, over and above this, facilitating their task of fanning the popular flame, are the economic causes of war…If nations can learn to provide themselves with full employment by their domestic policy (and, we must add, if they can also attain equilibrium in the trend of their population), there need be no important economic forces calculated to set the interest of one country against that of its neighbours.

There would still be room for the international division of labour and for international lending in appropriate conditions. But there would no longer be a pressing motive why one country need force its wares on another or repulse the offerings of its neighbour, not because this was necessary to enable it to pay for what it wished to purchase, but with the express object of upsetting the equilibrium of payments so as to develop a balance of trade in its own favour.

International trade would cease to be what it is, namely, a desperate expedient to maintain employment at home by forcing sales on foreign markets and restricting purchases, which, if successful, will merely shift the problem of unemployment to the neighbour which is worsted in the struggle, but a willing and unimpeded exchange of goods and services in conditions of mutual advantage.

Keynes realized that the economic consensus of his time had destabilized the international system by forcing businesses to fight over scarce global demand. Hard limits on governments’ budgetary flexibility forced policymakers to choose between taking care of their own citizens—at the cost of harming innocent people elsewhere—or upholding their obligations to their neighbors by sacrificing their own workers. Either way, the causes of peace and democracy were threatened.

Keynes offered shared prosperity as a way out. Governments could transcend the zero-sum mercantilist world by removing self-imposed constraints on spending and borrowing. (Although that could lead to new, different problems.)

Later, while working on the postwar settlement at Bretton Woods, Keynes concluded that domestic reforms might not be sufficient by themselves, which was why he pushed for the creation of new international institutions to manage the volatility of cross-border financial flows.

Long-term low-cost capital was needed to support reconstruction and development, so we got what is now called the World Bank as well as (eventually) the other multilateral development banks: Inter-American, Asian, African, and European. Shorter-term flows were supposed to be limited by regulatory controls, and just in case, there would be a backstop offered by a specialized lender that could offer emergency financing in exchange for policy changes. The resulting International Monetary Fund was different from what Keynes had in mind but nevertheless was positioned to play a constructive role in stabilizing the system compared to pre-war arrangements.

Yet despite figuring all of this out 80+ years ago, Keynes’s insights were (apparently) forgotten

The official response to the financial crises that followed the 1970s LDC lending boom was to force borrowers to slash their spending without any offsetting response on the part of creditors. By 1984, some of the largest trade surpluses in the world (in U.S. dollars) were being generated in Mexico, Brazil, Venezuela, and Argentina. Debt writedowns were not offered until 1989.

Even if this had been the best outcome for the LDC creditors, which is not obvious, it was a disaster for the people who lived in those countries as well as everyone else in the rest of the world who had previously exported goods and services to the crisis countries. Was this a conseqence of earnest officials following the economic orthodoxy of the day? Or, alternatively, was it the product of cynical political bargaining among those with decisionmaking power? Either way, the effect was to support the wealth and incomes of a narrow group of elites at the expense of the much broader mass of workers and consumers across countries.

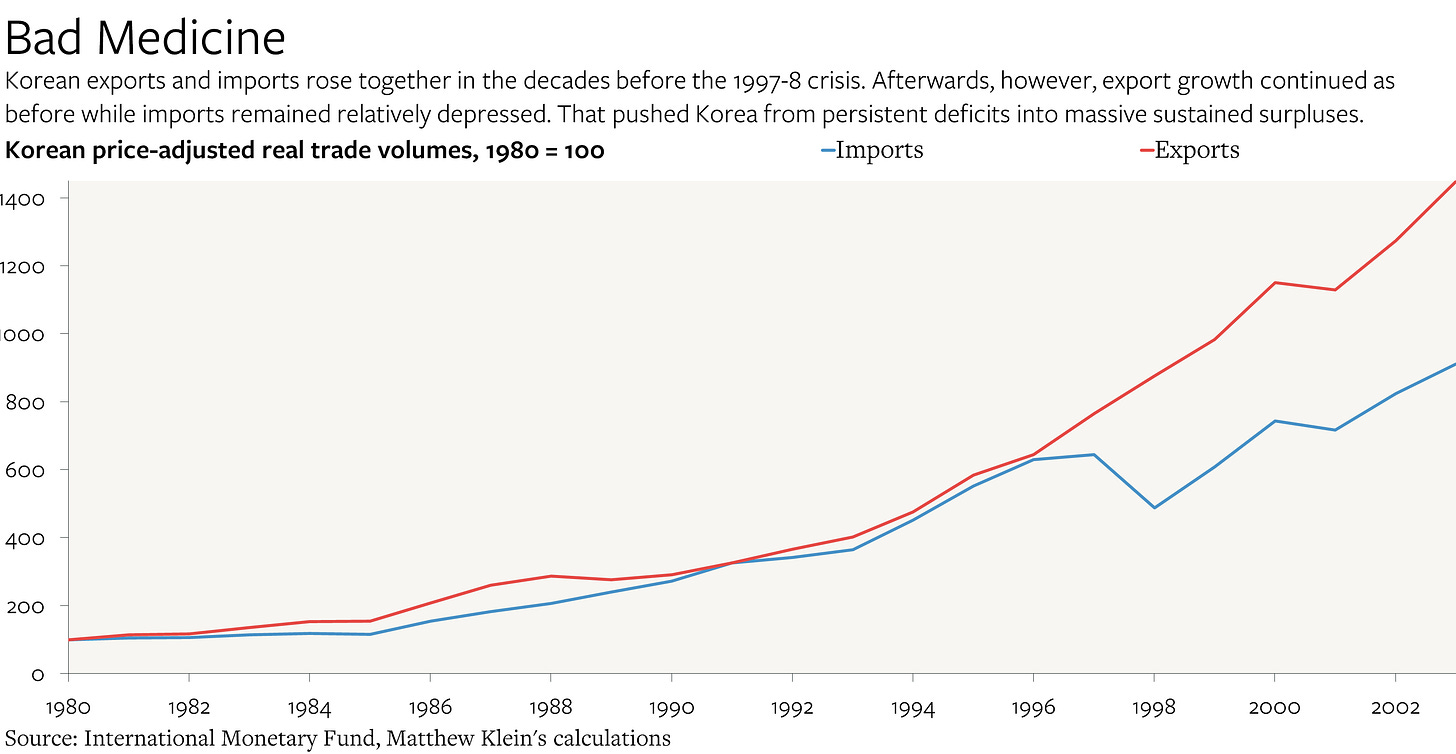

This kept happening. When the Soviet Union collapsed a few years later, its successor states were saddled with the old regime’s massive foreign debts. That made the transition from Communism that much harder to pull off and also ended up being a significant factor in Russia’s 1998 default.2 Mexico’s crisis in 1994-5 and the financial crises that hit Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Korea in 1997-8 were all followed by periods of austerity and extremely sluggish growth in imports relative to exports.

Argentina had its own severe crisis shortly thereafter, with real imports falling 68% between 1998 and 2002, while Brazil had a near-miss that nevertheless led to a drop in import volumes during a period when real exports were surging.

The result was that the combined current account balance of these economies swung from a yearly deficit of $75 billion (spending in excess of income) in 1997 to a yearly surplus of $77 billion by 2003, for a net change of $152 billion.

The responses to these balance of payments crises were a massive drag on global demand. The impact was compounded as other countries—particularly China, Singapore, and Taiwan—watched what happened with horror and adjusted their own policies to protect themselves from future crises by building up massive savings buffers.3

These efforts at self-insurance were the result of policy responses to crises that favored debt repayment and creditor protections over enlightened self-interest. That exacerbated the parallel but related trend towards rising income concentration within many of the major economies. The shifts in spending power towards entities that spend relatively little on the goods and services that create jobs and incomes for others was comparable in both magnitude and impact to the changes happening in the 1990s crisis countries.

Ordinary Americans were on the other side of all this. Export income stagnated and millions of jobs were lost, but spending on imports ballooned—along with household debt. The U.S. current account deficit widened from about $130 billion 1997 to $530 billion in 2003, and only got bigger in the following years.

Even if they had understood all of these forces in real time, American policymakers were limited in what they could do in response. If people in the rest of the world (as well as rich Americans and U.S. corporations) were unwilling or unable to buy goods and services, but were happy to buy U.S. financial assets, somebody in the U.S. was going to have to borrow and spend money in size to prevent a global depression. From that perspective, the role of the federal government should have been to act as an intermediary that absorbed these unsolicited financial inflows and directed them into relatively benign uses.

As Michael and I put it in Chapter 6 of Trade Wars Are Class Wars:

In retrospect, the best response would have been for the federal government to borrow as much as necessary to accommodate the excess inflows and to spend the money supporting demand for U.S. manufactured goods, investing in infrastructure, reversing the policies that had led to the concentration of income, and reducing poverty. Domestic spending would still have outstripped domestic production, but the overall composition of economic activity would have been less distorted. American manufacturing would not have been unduly displaced by imports, there would likely have been no housing bubble, and the increase in U.S. debt would have been borne by the entity (the federal government) best able to bear the burden.

While this was not done at the time, our suggested approach bears some resemblance to actual U.S. policies over the past two years.

The Underlying Problems Have Not Gone Away

There is still a large mismatch between the global bid for financial assets and the actual financing needs of the economies issuing those liabilities. The 2010s did for Europe what the 1990s did for East Asia, while the return of high energy prices has once again led to a windfall for oil and gas exporters.

There was a boom in lending to poorer countries in the years leading up to the pandemic, but even though the borrowers might have benefited from additional capital investment, the loans generally failed to increase long-term debt servicing capacity.

In fact, many countries ended up spending a much larger share of their foreign income on interest and principal repayments than they did before. These borrowers are now being forced to slash their spending on imports—at great cost to their living standards—while some are being pushed into the arms of regimes hostile to the U.S. but that are offering concessional balance of payments support.

Of particular relevance to the hosts of our discussion, the surge in debt burdens has often been especially acute for poorer countries with potential strategic importance, such as Egypt, Ethiopia, Jordan, Kenya, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Note that the data end in 2021, and that debt burdens had been rising sharply even before the pandemic.

Moreover, the credit expansion to the underdeveloped parts of the world was dwarfed by the net financial flows to places that did not need the money, particularly the U.S. and the other Anglosphere economies.

Taken together, the problem is threefold:

There is not nearly enough spending relative to income in certain places

There are many unmet investment needs in lower-income places that unfortunately seem to have trouble raising and mobilizing funds effectively

As a result, there is far too much cross-border lending to places that ought to be able to finance themselves domestically, with all of the distortions and costs that entails

This is perverse—and to the extent that this situation has been made possible by the open international system, it is an indictment of that system as it has existed in practice over the past several decades.

As the hosts of our discussion noted, better U.S. domestic policies alone are insufficient to solve this problem, even if they would be a significant improvement. There should be an international component to the policy mix as well. But what should that look like?

Losing Money Abroad as Enlightened Self-Interest

My suggestion was that the U.S. government4 could build on its role as an intermediary of these destructive cross-border flows by massively expanding its provision of development finance and balance of payments support to the rest of the world. The catch is that the U.S. government would have to be willing to endure substantial losses on this international investment portfolio. I think that is a price well worth paying when viewed in light of the alternatives, but it should be acknowledged up front.

After all, the private sector has no problem financing profitable projects. For much of the past decade, it also financed plenty of unprofitable ones. The global public sector—whether it is the Bretton Woods institutions, trade financing bodies, China’s state-backed forays into development lending, or more recent efforts by Gulf monarchs to prop up their oil-poor neighbors—has also been more than willing to lend to borrowers who may or may not be able to pay back the money.

Yet all of this financing has nevertheless been insufficient to generate the desired combination of global macroeconomic outcomes, much less support global development objectives. There might be plenty of financing going to poor places, but not nearly enough to sustainably raise living standards and protect against crises. Complaints about low yields in the rich countries make it clear that the constraint has been a lack of credible places to invest, rather than a lack of financing. If even more money is going to go out the door, it will necessarily be going to borrowers who are even less capable of paying it back at market rates of return.5

So if the U.S. government were committed to meeting financing volume targets that were determined by macroeconomic objectives and development goals—to say nothing of strategic concerns—policymakers would have to be willing to incur some sort of fiscal cost.

Remember, the point is to originate and guarantee loans that borrowers can “repay” without exerting much effort. Burdening the world’s poor with new debts they cannot service would not be helpful. In practice, some combination of extremely concessional terms and explicit—and frequent—debt forgiveness would be required. Other, more creative structures with equity-like characteristics could probably obscure the fiscal impact while also being better for the recipients, but there is only so much that financial engineering can accomplish. The cleanest and most transparent approach would be outright grants, such as using appropriations to cover the cost of solar farm installations in North Africa,6 although this might be a tougher sell for the domestic U.S. audience.

(If the U.S. government could somehow pass the costs of these money-losing ventures onto the ultimate savers in the surplus societies, so much the better, but I am not sure how to make that work.)

While the fiscal costs of this new internationalism could be substantial, the overall result—in the absence of fundamental changes to the political economies and income distributions of the major surplus societies—would nevertheless constitute an improvement for most Americans as well as for many people in poorer countries. U.S. international economic policy would be prioritizing the Keynesian concerns of world peace, democracy, full empoyment, and productive investments in our shared future over the interests of those who are unwilling to spend what they earn on goods and services.7 If the U.S. government is looking for a foreign agenda to match its domestic ambitions, consider this one.

Zach Carter’s biography—appropriately titled The Price of Peace—does an excellent job of explaining the connections between Keynes’s theoretical work and his concerns about life and death.

Another big problem was the collapse in the prices of Russia’s main exports thanks to the crises in East Asia.

I can only imagine how the Chinese Communist Party leaders felt as they watched the humiliation and abrupt end of the Suharto regime.

For the sake of simplicity I am not going to go into the numerous agencies and public corporations that could be deployed in this effort. The Federal Reserve already provides substantial support to preferred borrowers via its swap lines, but these could be expanded to include a broader group of counterparties if the Treasury were willing to bear the credit risk.

Those saying that the World Bank and its peers could afford to stretch their credit ratings are effectively making this same argument, albeit in different words.

Honestly the Europeans should pay for that particular project. This piece is written from the perspective of the U.S., but there is no reason why Europe, the U.K., Canada, Japan, Korea, etc could not have similar policies. While there are plenty of domestic reforms that the German government should do to increase Germans’ living standards, for example, there are also plenty of places that could benefit from German economic assistance if the surplus remained stubbornly high. (It is also worth noting that China tried development lending as way to recycle its surpluses via the Belt and Road Initiative, but apparently got sick of losing money and is now something of an obstacle to debt relief for many impoverished countries.)

Also, it might strengthen America’s global prestige at the expense of regimes who often happen to be hostile.

It is encouraging to read an analysis where Argentina is not described as a country of bandits. The nuance of your report is outstanding. Thanks!

While laudable in intention and logic, where it breaks down for me is who gets the money. Corrupt government players in these countries have forever ended up with the funds from grants and so forth. And the people in the countries they sit on top of stay poor and abused. Btw, many young entrepreneurs in whose companies I invest have “escaped” (their words)from Argentina, for example, and emigrated to Uruguay and other places with more liberal economies. Same is true for South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria…. They all lived there and couldn’t wait to get out, leaving lives and families behind in the process. Keynesians forget that the human condition is polluted by a panoply of bad actors who exploit their economic analysis to further their power grabs, including in the good ole USA.