Hosting the Olympics as an Economic Development Strategy

"Big push" investment booms often fail without reforms that lift productivity

As the summer games draw to a close in Tokyo, it’s worth reflecting on a question that David Schawel posed a couple of weeks ago:

While there are many reasons to want to host the games, cities and countries often justify their bids by arguing that it’s a kind of development strategy, where spending a lot of money upfront will pay off in the future. I think we can learn something useful about economic development by trying to answer David’s question from that perspective.

Hosting the games is rarely beneficial because borrowing a lot to build physical capital only helps societies get richer in specific contexts. Outside of rare circumstances where wars or natural disasters have destroyed the existing capital stock—or prevented societies from investing as much as they should—additional physical capital only becomes valuable with complementary social, political, and cultural improvements.

Without those other changes, all that remains after an investment spree are bad debts and a legacy of maintenance costs for buildings and infrastructure that people don’t need. This is why (I think) most cities have failed to benefit from hosting the Olympics—and also why most societies that have attempted to rapidly industrialize through “big push” investment spurts have failed.

Which cities have benefited from hosting the Olympics?

Many economists have compared the direct costs of hosting the games against revenues from television rights and tourism, but that’s not really what David was asking about. While that’s a reasonable starting point, it’s an unnecessarily narrow view that implies it’s basically never worth hosting the games.

What really matters is if the investments made to accommodate athletes and tourists—and the global publicity provided by airing the games to audiences all over the world—attract businesses, workers, and visitors in ways that boost living standards years later. From this perspective, it’s irrelevant whether or not the municipal government loses money from hosting the games themselves. Unfortunately, it also means that anyone claiming that the Olympics were good or bad for a city is at risk of being stuck in an endless argument.

With that caveat, I think that the answer to David’s question is greater Salt Lake City, which hosted the 2002 winter games. The decision to host the games in the mid-1990s encouraged significant social changes that eventually made greater Salt Lake more attractive place for non-Mormons.1 Once the games actually began in 2002, it was increasingly clear to many Americans that greater Salt Lake City is a desirable place to live for anyone interested in an affordable urban lifestyle and great access to the outdoors.

There are only a handful of U.S. metros that are large enough to be desirable for employers that also have comparable access to mountains: Denver, Portland, the San Francisco Bay, and Seattle. But all of those cities are significantly more expensive, with the gap only growing over time.

That realization eventually drew in workers from the rest of the country as well as larger—and higher-paying—businesses. The new residents and employers reinforced the changes that had already been underway, making Salt Lake City even more attractive than it had been as a direct result of hosting the Olympics. Since hosting the games, total employment income in greater Salt Lake City has grown substantially faster than in other large U.S. cities, including fast-growing metros such as Atlanta, Dallas, Denver, Las Vegas, Miami, Phoenix, and Portland.2

Other cities that likely benefited from hosting the games include Atlanta in 1996, Barcelona in 1992, Seoul in 1988, Los Angeles in 1984, and Tokyo in 1964. My list is based more on my subjective impressions than pure quantitative criteria, which means you might come up with slighly different answers, but I also think my list is defensible when thinking about the longer-term trajectories of each of those metro areas in the decades since they hosted the games. Crucially, in none of those successful cases were the physical infrastructure investments the main driver of the host city’s subsequent fortunes, even if they were helpful.

Like Salt Lake City, the Atlanta games pushed the city to become more cosmopolitan and business-friendly, which eventually led to a virtuous circle of migration and business investment. Barcelona became a much bigger tourist destination following the 1992 summer games thanks to the attention it received, although it was already starting from a high base and was already one of the most prosperous regions in Spain.

Chun Doo-Hwan’s military government bid for the games in 1981 as part of the “3S policy” to mollify the Korean population with social liberalization after the Gwangju Massacre. Preparing for the games necessarily meant opening South Korea up to greater international influence, which in turn encouraged the transition to democracy in the late 1980s.

Los Angeles actually made money from the games because it was able to keep costs low and get a high share of TV revenues. The 1964 Tokyo games were an important demonstration of Japan’s openness to the world and coincided with the start of the fastest period of convergence with U.S. living standards in any major country on record.

That’s a short list, and while I am willing to be persuaded that more cities could be included, I don’t think we can add too many more with confidence. In most cases, the skeptics are right. The 2014 winter games in Sochi might have been the biggest fiasco, but it’s far from the only one.

The 1976 Montreal games were so financially damaging that Los Angeles was the only city willing to place a bid to host the 1984 games.3 The 2004 summer games in Athens saddled the Greek government with debt it couldn’t afford and left the city stuck with facilities it rarely used again. The 2016 Rio games left Brazil saddled with hard currency debt in the midst of its worst economic and political crisis in a generation. The Council on Foreign Relations published a useful overview of the issues and the most recent research a few years ago.

The Sochi example is particularly noteworthy. The Russian government justified the $55 billion they spent developing the subtropical Black Sea resort in part by arguing that the mountains nearby would attract skiers who previously would have gone only to the Alps or the Rockies, generating enormous tourism revenues and associated job gains. Even if the climate had cooperated with that ambition, Sochi failed to live up to its promise because the Putin regime had turned Russia into a pariah state between 2007, when the city won the bid to host the games, and 2014, when the games actually occurred. The physical investments might have been nice, but they were ultimately irrelevant.

The limits of investment-led growth without reforms

The problem that afflicted Montreal, Athens, Sochi, Rio, and many other cities was that they borrowed lots of money to build things that are only worthwhile if they can be used for many years, such as highways, sports stadiums, and hotels—only to never use those things again. They thought they were making valuable investments, but they were actually wasting labor, raw materials, and their access to financial markets on boondoggles. Even if some individual projects were worthwhile, the overall consequence was that the cities ended up worse off than they were before.

This is a frequent problem for societies that try to industrialize quickly. While Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan all transformed into rich countries in the space of a few decades by, among other things, encouraging massive investments in physical capital at the expense of consumer spending, many societies that have tried to follow their path ended up failing spectacularly. Even those that avoided the worst outcomes often ended up stagnating for decades after an initial spurt of “miraculous” growth.

The difference between the rare successes of the investment-led growth model and the more common disappointments can be explained by whether or not a given society has the “software” necessary to take advantage of any “hardware” upgrades. This passage from Chapter 4 of Trade Wars Are Class Wars gets at the nub of the issue:

Risky long-term projects make sense only in particular social and institutional contexts where the risk of expropriation is low, financial markets are stable, regulations are unobtrusive, contracts are honored, and the rules of the game are unlikely to change unexpectedly. Countries with these conditions should naturally be able to absorb far higher levels of investment per person than countries without these conditions.

The capital stock should therefore be much higher in places where governments are accountable to the people and constrained by laws and a strong civil society. By contrast, high rates of corruption, vague regulations, and arbitrary rule are natural obstacles to productive investment.

It’s theoretically possible that investing in physical capital in a low-trust society could induce changes in politics and culture that raise the value of those investments, leading to a virtuous self-reinforcing process of higher capital spending and rising living standards. But there aren’t many examples of this “if you build it they will develop liberal institutions” phenomenon in the real world. (Some people point to the Tennessee Valley Authority, although I’m unconvinced.) Instead, what generally happens is that societies hit a limit, where investing more—either by borrowing from abroad, by squeezing consumer spending, or some combination—is counterproductive.

Modern China provides examples of both catastrophic failure and modest success

The Great Leap Forward (1958 to 1962) was an attempt to rapidly transform China from a poor agrarian country that had been ravaged by more than a century of imperialism, foreign invasion, revolution, and civil war into an industrial economy.

Operating under the mistaken belief that collectivization and “Marxist” farming techniques would dramatically increase agricultural output, the Communists seized food to export for hard currency, forced tens of millions of peasants to become laborers for heavy industrial projects, and even melted down valuable farm equipment and cooking tools for the metal content. Tens of millions of people starved to death.

The price was steep, but unlike the Soviet Union, which endured its own famine during its rapid industrialization in the late 1920s and 1930s, China didn’t even end up with any durable gains from the experience.4

Things have worked out much better in China’s more recent investment-led growth push, but—and this is where you’re going to want to read Trade Wars Are Class Wars for the full treatment—there are good reasons to think that the biggest gains have already happened. China benefited from the investment surge of the 1980s and 1990s because that was necessary to correct for years of underinvestment and to take full advantage of the gains of “reform and opening”.

Things changed by the early 2000s. Initially, the costs of China’s no-longer-appropriate development model were transferred abroad via the trade surplus and the commensurate surge in borrowing by China’s trade partners, most notably the U.S. After the financial crisis, China’s imbalances shifted inward, with an unprecedented surge in domestic indebtedness alongside a sharp slowdown in growth. As Michael Pettis has written for years—and as China’s own leaders have repeatedly said in public—further economic development requires a big shift in the model. So far, however, that hasn’t happened.

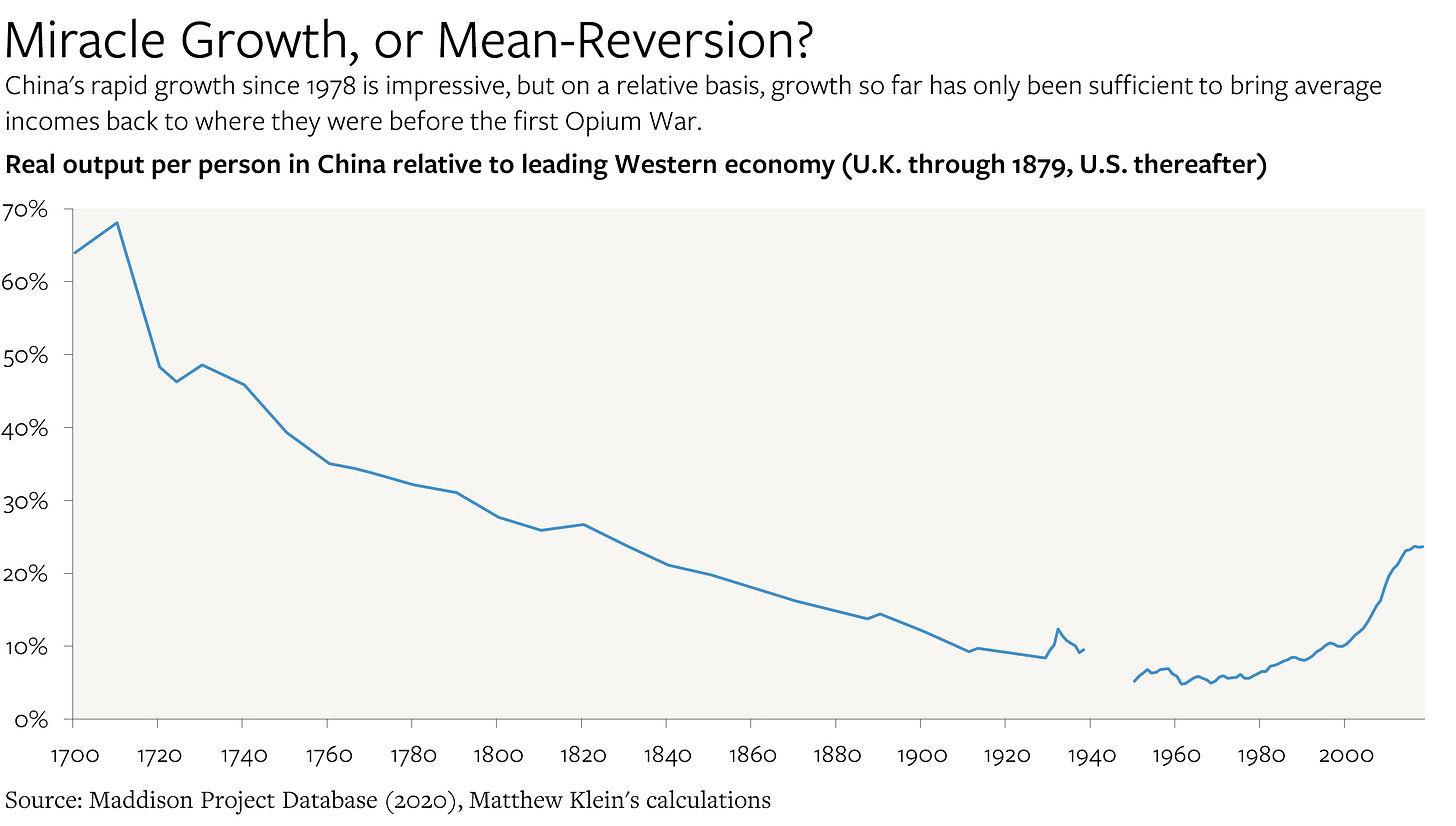

Unfortunately for China, the country didn’t get very far before the pre-pandemic slowdown. Using the latest iteration of the Maddison database published by the University of Groningen, it looks as if the average income in China on the eve of the pandemic was just under a quarter of the U.S. level—and that’s after adjusting for differences in relative prices, which makes Chinese incomes look higher.

It’s a huge improvement compared to 1978, when the average income in China was just 6% of the U.S. level, but it’s essentially the same as in 1830, when China’s average income was about a quarter of the average British income. Moreover, convergence seems to have paused (or stopped?) around 2014.

From this perspective, the right comparisons for China might be Brazil, Mexico, and the Soviet Union, rather than Japan, South Korea, or Taiwan.5 In those less successful cases, periods of rapid convergence lasted for decades, lifting average incomes relative to the U.S. by as much as 20 percentage points. But then, for whatever reason, convergence stopped. As of 2018, China has a lower GDP per capita, adjusted for differences in relative prices, than any of those other societies.

It’s telling that the most extravagant construction projects associated with the 2008 Beijing Olympics, such as the “Bird Nest” stadium, haven’t been used enough since to justify their cost and upkeep. At best they are tourist attractions bringing people in for their novelty, rather than valuable investments that improve people’s lives. On the other side are the hundreds of millions of rural poor in China who continue to lack access to basic healthcare and education, as Scott Rozelle and Natalie Hell have documented.

The Beijing Olympics obviously aren’t to blame for the persistence of rural poverty in China. But both can be explained by the Chinese government’s longstanding preference for showy capital investments over the provision of public services. That’s not the best way to do economic development except in a few unusual circumstances. And that’s why cities that host the Olympics often suffer: they shift scarce resources from valuable but unsexy projects to global spectacles that provide no lasting benefit.

My family began vacationing there regularly in the early 1990s, but back then it wasn’t a place we would seriously consider living full time. If you’re remotely into hiking, I would strongly recommend visiting Mt. Timpanogos and the High Uintas.

The major metro areas where total employment income has grown faster than Salt Lake City since 2002 are Austin, Houston, Nashville, the San Francisco Bay Area, and Seattle.

In fact, Montreal’s woes contributed to LA’s good fortune. As the only bidder for the 1984 games, the city had leverage to extract unusually favorable terms from the International Olympic Committee. Most notably, LA wasn’t required to build any new stadiums, event venues, or hotel rooms. That meant that LA is the only city to generate a substantial profit from hosting the games. LA’s financial success encouraged more cities to bid, shifting bargaining power back to the IOC, which then demanded much more expensive sports facilities and other infrastructure. The pendulum seems to have swung back after the excesses of the 2000s and 2010s, with the IOC choosing (in 2017) to allocate the 2024 and 2028 summer games to the only two cities that submitted bids for the 2024 games: LA and Paris.

The definitive account of the Great Leap Forward is Tombstone by Yang Jisheng. It’s a brilliant and incredibly important book, but I should note that I was only able to read it in small doses because of the subject matter was so depressing. And supposedly the Chinese-language version, which is much longer, is even darker. He has a new book out on the Cultural Revolution that’s on my list.

Iran is another interesting case study, with both non-oil GDP and non-oil investment as a share of economic output surging between the coup of 1953 and the revolution of 1979. I didn’t include Iran in the chart because the Maddison data don’t allow for the distinction for oil-related and non-oil GDP.