How Many Benign Inflation Prints Are Enough?

We should be cautious about overemphasizing the data from May and June

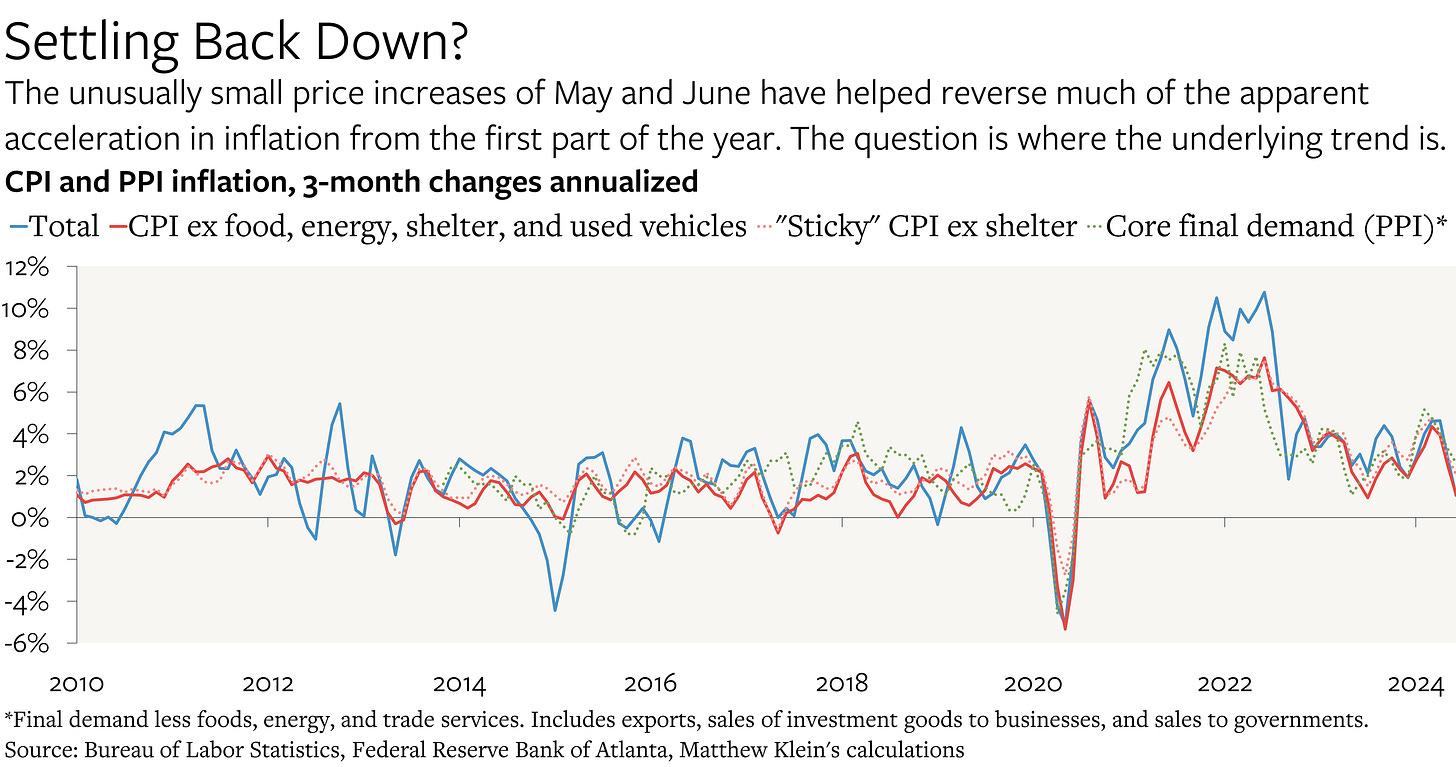

The U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) fell by 0.056% in June on a seasonally-adjusted basis. In May, the CPI rose by only 0.006%. This is therefore the second consecutive month of inflation data that Federal Reserve officials could plausibly consider “good enough” to at least make them start thinking about adjusting their policy stance. It is also the slowest stretch of inflation over a two-month period since the start of the pandemic. While falling energy prices have been helpful over the past two months, the overall numbers are consistent with other measures that strip out some of the more volatile or idiosyncratic components of the CPI, as well equivalent measures for the Producer Price Index (PPI).1

Interest rate pricing has shifted accordingly, with markets now implying that there is a 90% chance that the Fed will begin lowering rates at its September meeting, up from 58% as recently as two weeks ago, and up from 42% since the end of May. The yield on 2-year U.S. Treasury notes has dropped by about half a percentage point over the same period.

The most recent news on inflation has certainly been welcome—and it also comes at a time when some measures imply that the job market is weakening. While there is (or should be) more to monetary policy than mechanically raising interest rates when inflation accelerates and lowering them when the unemployment rate ticks up, the picture painted by the latest data is somewhat similar to other times when the Fed has recalibrated policy, most obviously in 1995-1996. That helps explain the shift in both market pricing and the tone of many Fed officials.

The question is whether this reaction is appropriate, or premature.

Officials understandably want to avoid pushing the economy into a downturn if it can be avoided, which means being willing to preempt signs of weakness before they appear. If monetary policymakers wait until after companies start cutting capital spending and hiring, they will likely be too late to prevent a painful contraction.

But there is also a countervailing risk: policymakers may be overemphasizing the significance of the latest data and underemphasizing the possibility that at least some of the recent slowdown in inflation (and job market weakening) may be noise. In that case, lowering interest rates would be unhelpful, unlocking more borrowing and nominal spending than needed to keep the economy growing at an even pace.

I am not sure which analysis is correct, but I am wary of taking two months of benign inflation prints as proof that inflation will remain subdued, and that monetary policy therefore needs to be recalibrated. Many analysts rightly believed that the unusually rapid price increases of January-April 2024 were overstating the underlying inflationary trend. Why should the unusually modest price increases over the past two months have any more signal, especially if it may not be consistent with the data on wage growth? What follows is an attempt to sort through these questions.

Inflation Slowdown, Or Catchup Disinflation?

Monthly data are often noisy even when they are not being distorted by seasonal patterns. It is inherently tricky to distinguish between random movements that might get canceled out or revised away, and changes in underlying trends that demand our attention.

While it is possible that trend inflation has decelerated sharply, my suspicion is that the most recent prints are a form of payback from the surprisingly hot readings in the first few months of the year. If those earlier prints were reflecting new year’s price resets rather than underlying trends, as many analysts argued, it would make sense for subsequent inflation numbers to come in somewhat cooler even if the overall rate of inflation in 2024 were on track to be unchanged from 2023.

There is no way to prove this either way, but the following picture is suggestive.