Immaculate Disinflation Hopes Dashed?

The latest data on wages suggest that declining job market churn has not been sufficient to normalize the pace nominal income growth.

The latest data from the U.S. suggest that inflation may be too entrenched to go away entirely on its own. While the headline rate of inflation probably peaked over the summer, underlying price pressures have proven remarkably stubborn despite the apparent normalization of the public health situation. The benign scenario—inflation decelerates to ~2% a year without the economy rolling over—is still possible, but it looks less likely than I would have imagined a year ago. This explains why Federal Reserve officials believe that they will need to continue tightening financial conditions to force consumer and business spending lower.

The problem is that the rate of improvement (third derivative of prices with respect to time) seems to have stalled, making the prospects for a soft landing look worse than even a few weeks ago. Unless that changes, inflation net of temporary factors will probably persist around 4-5% a year. While some (many?) might find that outcome acceptable, especially if the alternative is a painful downturn, the officials making decisions today do not seem to view current circumstances as an opportunity to modify their policy targets.

A Quick Recap of How We Got Here

Most of the inflation that consumers have experienced in the past two years is attributable to the disruptions of the pandemic and the war. Sudden changes in our ability to produce goods and services collided with dramatic shifts in the mix of goods and services we wanted to buy. Markets responded—as they should—with large shifts in relative prices. Many governments rightly did what they could to smooth this adjustment process by disbursing money to consumers and businesses to avoid waves of defaults and debt deflation.

While this was far better than the alternative, it meant that some inflation would be likely. The total level of nominal spending consistent with a given amount of real economic output rose, which put upward pressure on the prices of many goods and services. No one seems to have found an escape from this dilemma. The U.S. is unique among major economies for having recovered as well as it has in terms of total production and real consumer spending. Everyone else has done worse on those measures, including those places that have had superior public health outcomes and less inflation.1

Given all this, it was reasonable to expect that, at some point, most of the unwanted inflation would simply go away on its own. Some prices that had spiked earlier on might fall, but more importantly, the overall pace of price increases would revert to pre-pandemic norms as the health situation improved, the disruptions faded, and emergency measures were lifted.

The big question was always going to be whether this process would occur before workers, consumers, and businesses decided that they needed to alter their behaviors to protect themselves from the risk of future inflation. As I put it last year:

Instead of focusing on how to acquire or provide as many goods and services as possible to satisfy demand, they would instead become more concerned with hedging their inflation risk by hoarding physical commodities and moving purchasing power out of the country…If businesses become worried that costs are going to keep rising at unpredictable and accelerating rates, they won’t want to tie up cash in long-term projects that take time to generate returns. Even if individual executives wanted to make those kinds of plans, investors wouldn’t finance those projects except under punishing terms, with high real interest rates and low equity market multiples. This is why central bankers talk so much about the importance of “anchoring longer-term expectations.”

Lael Brainard, the number two Fed official, made a similar point in a recent speech to justify why the central bank had to tighten even if the problems were coming from the supply side:

Even when each individual supply shock fades over time and behaves like a temporary shock on its own, a drawn-out sequence of adverse supply shocks that has the cumulative effect of constraining potential output for an extended period is likely to call for monetary policy tightening to restore balance between demand and supply…Even in the presence of pandemics and wars, central bankers have the responsibility to ensure that inflation expectations remain firmly anchored at levels consistent with our target.

This perspective explains why the pace of worker pay increases is so important. These contracts reflect employers’ beliefs about future revenues and also affect the trajectory of economy-wide spending.

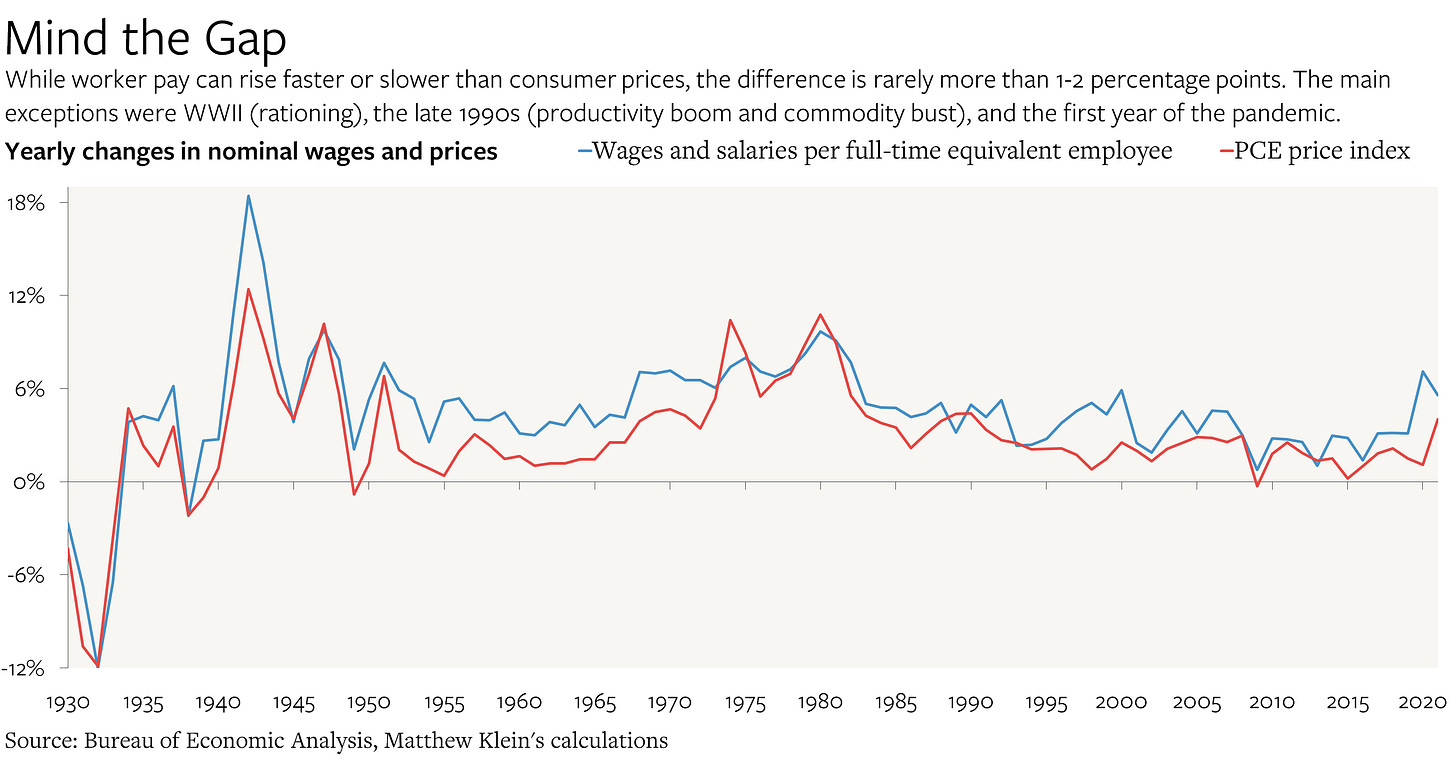

It’s not so much that higher wages push up costs for businesses that then pass price increases on to consumers, although that dynamic can be relevant for certain sectors. Instead, the bigger issue is that employment income is the largest and most reliable source of financing for consumer spending. Wages can rise 1-3 percentage points faster or slower than consumer prices for a variety of reasons—including but not limited to compositional and definitional differences—but larger gaps between the growth rates of wages and prices basically don’t exist outside of WWII and Korean War rationing, the late 1990s productivity boom, and the first year of the pandemic. The only time U.S. wages rose at least 4 percentage points faster than prices for at least two years in a row was 1941-1943.

Fed boss Jerome Powell made a similar point recently as well.2

To be clear, rapid wage growth during the post-vaccine reopening did not doom us to a period of sustained inflation that would only end with an economic downturn. After all, the pandemic disrupted the job market just as it disrupted everything else. At least in the U.S., tens of millions of people lost their jobs and were then rehired, often in new roles in entirely different industries, reflecting radical shifts in what people wanted to buy and the conditions in which people were willing to work.

That led to enormous churn in the job market. Workers quit their jobs for better opportunities elsewhere—including self-employment and entrepreneurship—at far higher rates than they had in decades. Employers in booming industries posted more job openings to attract workers, while those in other businesses posted more openings to backfill positions that had become vacant. One-off recalibrations of wage levels encouraged people to move to—or stay—where they were most valued. An increase in the overall level of wages made these relative comp adjustments easier for everyone.

It was reasonable to believe that this process would eventually end. Just as the markets for home gym equipment, toilet paper, and suburban housing normalized after an initial panic, so too would the market for labor. Falling churn would reduce wage pressures (and nominal spending) without the need for policymakers to impose job losses on workers. And, in fact, there have been some notable improvements in measures of job market churn. Unfortunately, the process has not gone far enough to be consistent with inflation of around 2% a year. Worse, the latest data suggest that the rate of progress seems to have stalled.