"Slouching Towards Utopia" and "The Long 20th Century"

Brad Delong's new history makes an important point well, and gave me a lot of food for thought. But I have some quibbles.

Certain moments are decisive breaks between “before” and “after”: think of the invention of agriculture, the birth of monotheism, the Columbian exchange, or the American Revolution. In Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century, Brad DeLong makes the case that 1870 is a hinge year in some ways more significant than 1492 or 1776.

Until 1870, more or less, technological progress had been so slow that the average person’s living standards had grown by just 0.005% a year since the invention of agriculture. (And those living standards were arguably lower than what had been enjoyed by the typical pre-agrarian hunter-gatherer.) There were gains in knowledge, but those had only been sufficient—barely—to sustain a larger population that remained at constant risk of disease and starvation. Both Aristotle and his intellectual descendents in the mid-19th century could claim, with some justification, that true freedom—including freedom from drudgery—was possible only for a select few, and that this freedom depended on the servitude of many others. Even the remarkable advances of the first industrial revolution had not been enough to move the needle, at least for most people. This was the context that led social reformers such as Thomas Malthus and J.S. Mill to call for public policies that would limit population growth.

That changed around 1870. Since then, both the total number of people and the average person’s living standards have soared. Despite the misery that humans inflicted on each other with world wars, man-made famines, totalitarian revolutions, and genocides, simple quantitative representations of human wellbeing go up and to the right after 1870 in ways that they simply did not before. Average incomes today are 9x what they were in 1870 even as the human population is 6 times as large. Combining these measures, Delong estimates that “the value of the stock of useful ideas about manipulating nature and organizing nature” is about 22x what it was in 1870.1

This was a momentous change in the history of our species, and it had enormous implications for anyone contemplating the good society. Serious thinkers suddenly found themselves wondering how to manage abundance—as well as the social changes created by the rapid evolution in the structures of production and consumption.

Mass migration from the countryside to the cities has created opportunities for billions of people, but also new challenges associated with dense urban living. It is not a coincidence that the social and political status of women rose as much as it did when child mortality (and therefore birth rates) collapsed, home appliances made cooking and cleaning far easier, and machines reduced the economic value of physical strength. It is also not a coincidence that some of the most violent social movements in human history arose in reaction to the constant disruption that went hand in hand with progress.

Delong’s ambitious book is an argument for recognizing how the world since 1870—the “long 20th century” that above all is characterized by unprecedentedly rapid change—is radically different than the world before 1870. It is also an attempt to explain how the sudden and dramatic acceleration in the pace of economic growth affected different societies, most notably the United States. (He repeatedly quotes Trotsky’s line that America is the “furnace where the future is being forged.”)

The central paradox, for Delong, is that the growth in humanity’s productive potential since 1870 should have been sufficient to create something like a “utopia” for everyone by now, at least by the standards of anyone alive in 1870. Yet despite the dramatic progress our species has experienced, we remain far from that ideal.

Part of the reason is that our desires have grown to match our capabilities. As Delong puts it, what were once considered luxuries eventually became conveniences and have since become essentials, even in lower-middle-income countries. Something like 70% of Indonesians have smart phones, for example. From that perspective, they might be wealthier than Rockefeller ever was, but they probably don’t feel that way.

The other problem is that the gains from innovation have not been distributed particularly evenly. Even within the richest societies, there are still millions of people who struggle with the pre-modern concerns of being fed, clothed, and sheltered. Billions more live at the threshold of subsistence outside the places that Delong calls “the global North”.2

There is a lot to like in Slouching. I particularly enjoyed the sweep of the narrative, the clear writing, and the digressions into the history of business and technology. The sections on Tesla’s collaboration with Westinghouse to commercialize alternating current and the explanation of how integrated circuits (semiconductors) work were among the highlights. Herbert Hoover’s career trajectory turned out to be a useful and entertaining framing mechanism for the first half of the book.

Most importantly, I have become completely convinced of Delong’s thesis that the world fundamentally changed in 1870—and changed in a way that it had never changed before. I definitely recommend the book to anyone interested in these questions.

However…

At this point, I should note that Brad has asked me multiple times to tell him what he got “BigTime wrong” in the book. What follows should be understood in that spirit.

Delong repeatedly says that the post-1870 break in humanity’s growth trajectory was due to “the triple emergence of globalization, the industrial research lab, and the modern corporation”. This is a compelling claim, and Delong spends a lot of time on the relationship between global integration and growth. But there is surprisingly little discussion of either industrial research labs or corporations. With remarkably few exceptions, we get almost no insight into how the post-1870 growth engine actually worked.

Delong basically admits that this was a deliberate choice on pages 167-168 of the hardback edition. In a revealing passage, he identifies a list of thinkers born in the Habsburg domains shortly before World War I who, in various ways, tried to restore and preserve what had worked before 1914: Joseph Schumpeter, Karl Popper, Peter Drucker, Michael Polanyi, Karl Polanyi, and Friedrich Hayek. (They stand in contrast to violent fantasists such as Hitler, Lenin, Mao, and Mussolini.) Delong says that, if he could have written a book that was twice as long, he would have written about all of the liberal Austro-Hungarians. I would like to read that book!

However, constrained by space, Delong decided to focus only on Hayek and Karl Polanyi—two men who were concerned with questions of political economy, specifically the relationship between markets and democracy.3 That fits well with Delong’s focus on the conflicts over how to distribute the gains of the post-1870 windfall, but I think it ended up detracting from some of his other arguments.

Delong claims that his book is supposed to be a story about how the “long 20th century” was distinct from everything that came before because of the importance of economic forces, as opposed to great power politics or ideology. But if that’s right, then there should have been much more focus on the history of modern business and applied science, and much less on political intrigues, elections, and wars. Given Delong’s stated priorities, Schumpeter and Drucker would probably have been much more relevant than Hayek and Polanyi.

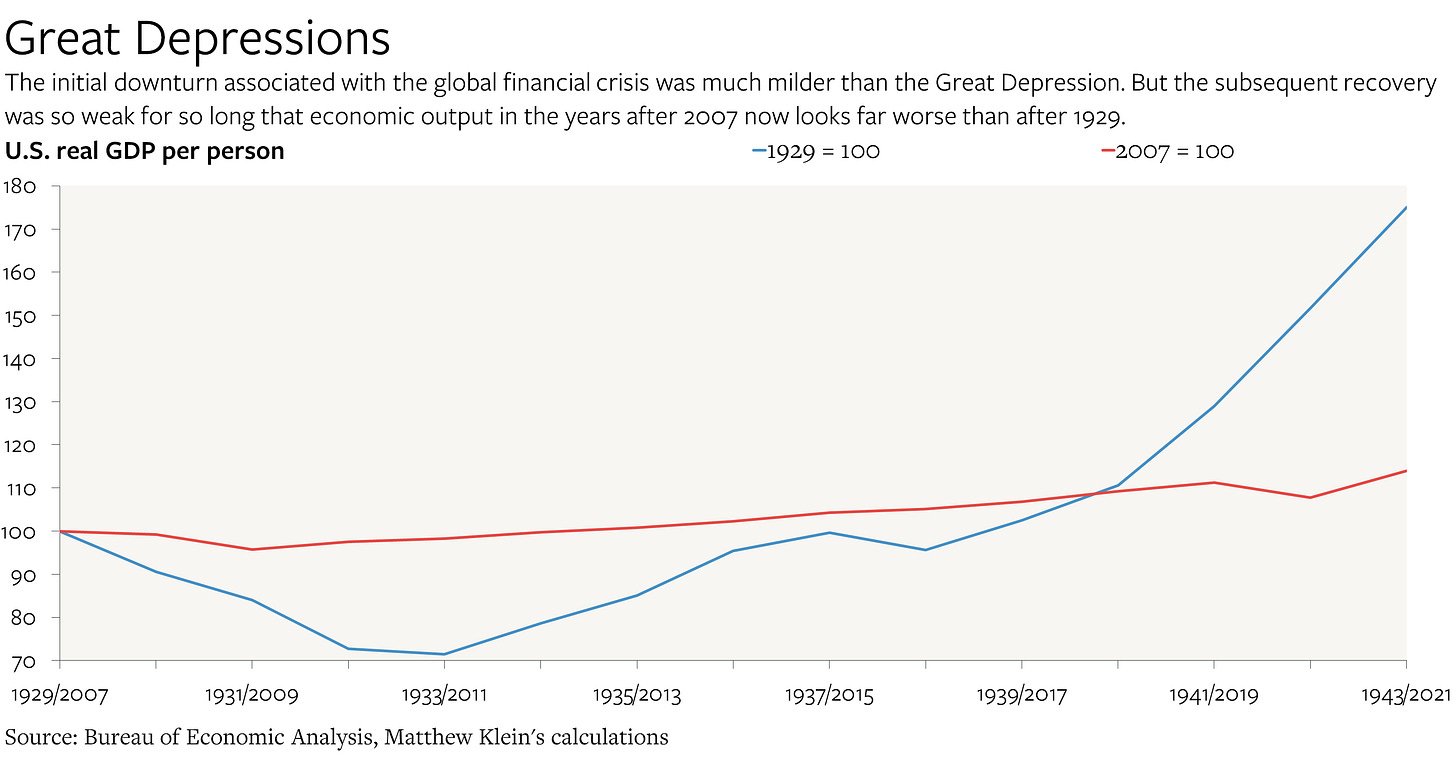

My other major criticism (I have a few narrower ones that I will mention lower down) is that I am not convinced that the “long 20th century” actually ended. The most persuasive argument, which is not quite the one that Delong actually makes, would be that the agonizingly slow growth in the years after the global financial crisis represents a fundamental break in the trend towards ever-rising prosperity. But that is a claim one could have made just as well in the 1930s—and it would have turned out to have been wrong.

Delong’s actual argument that “humanity’s time slouching toward utopia” stopped around 2010 is tucked in at the very end of the book. It rests on four claims that mostly relate to what he perceives as the diminished status of the U.S., which had been at the frontier of growth since 1870. First, the U.S. stopped being the unrivalled technological leader, with German and Japanese businesses catching up around 1990, “undermining the underpinnings of American exceptionalism”. Then came the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Then there was the global financial crisis, which was remarkable mainly because it demonstrated that “we had forgotten the Keynesian lessons of the 1930s and lacked either the capacity or the will to do what was necessary.” Finally, Delong highlights the failure of world leaders to address climate change: ”the Devil of Malthus taking, if not yet flesh, at least a form of shadow”.

For Delong, the “period to the long twentieth century’s exhaustion” was the election of Donald Trump, who “served as a reminder that pessimism, fear, and panic can animate individuals, ideas, and events as readily as optimism, hope, and confidence.”

This is not persuasive.

American companies remain at the technological frontier in everything from pharmaceuticals to microprocessor design to spaceflight and electric vehicles. Were the long wars in Afghanistan and Iraq really worse—or more damaging to U.S. society and global leadership—than the wars in Indochina? Was the fear of religiously-motivated terrorism worse than the fears of violence from anarchists, Weathermen, or militias? And while I would be the first to agree that policymakers committed an atrocity by failing to restore growth swiftly after 2007, the counterexample of China is not compelling, least of all to China’s own leaders, who have spent the past 11 years promising never to do it again.

Climate change is a serious problem that had not received the attention it deserves until recently, but there is little reason to think that it is a serious impediment to the growth trajectory humanity has experienced since 1870. People more knowledgable on the details of the legislation than I am believe that the climate-related provisions in the “Inflation Reduction Act” will be transformative. The main complaints come from Europeans who wish they could subsidize their own businesses just as much, not environmentalists.

It’s telling that Delong uses the pandemic as the culmination of his argument that America is no longer “an exceptional country”, pointing to the disproportionate number of people who died in the U.S. compared to Canada. The U.S. public health failure was inexcusable. Yet the U.S. response to the pandemic illustrates, in several important ways, that Delong may have been premature to call time on his “grand narrative”.

It was American companies, using American technology, organized by the American government through Operation Warp Speed, that delivered mRNA vaccines to the world.4 (It was also an American company that created what seems to be the most effective antiviral drug aimed at Covid.) Moreover, it was the U.S., more than any other country—by far—that exploited the latent power of the state to preserve jobs and incomes. China, rather infamously, did no such thing. The U.S. was the only major economy that was producing more at the end of 2021 compared to what had been expected by forecasters at the OECD at the end of 2019.

So while I am willing to believe that the “long 20th century” may have ended when Delong says it did—on the grounds that global growth has been much weaker than in the past—I have little reason to believe that this sad state of affairs must persist. I am an optimist who believes in the importance of contingency and human agency, what can I say?

Other Scattered Thoughts and Nitpicks

While I sympathize with Delong’s focus on the U.S., I also sympathize with those who think the book is too U.S.-centric. If the book had been more materialist in its focus—more of a history of how businesses and innovation have powered growth since 1870 in ways that they did not before—it would have made sense to devote relatively little space to other countries. But since Delong opted for a story about political economy, the paucity of material about Canada, Europe, and Japan, especially after WWII, is unfortunate.

This omission is particularly glaring in the section on the “neoliberal turn” in the late 1970s/early 1980s. Delong talks about race relations in the U.S. and writes that “fear of moochers was a significant part of what prompted the downfall of social democracy and the turn toward neoliberalism” (416). But is that really what explained the change in Germany, which arguably moved first? Or Mitterand’s heel-turn in France? Or the (modest and partial) rollback of social democracy in Scandinavia in the 1990s? Or the transition from Mao to Deng, for that matter, which was arguably motivated by the same basic set of concerns?

Keynes famously wrote that “anything we can actually do we can afford”. The unspoken corollary is that we can only afford the things we can actually do. Might this help explain the global nature of the “turn”? Was the “turn” a reaction to excessive policy ambitions in the 1960s and 1970s that ended up fueling inflation?

In general, I wish there were a lot more about Japan. “Why the Meiji Restoration Succeeded” is probably a book in itself, but I still would have liked more than what we got. And while I am glad that Takahashi Korekiyo is given his due for getting Japan out of the Great Depression early with proto-Keynesian policies, Japan’s experience since 1990 might have been helpful context for explaining what happened in the U.S. and Europe after 2007.

There was no mention of the provisional government in Russia that followed the February revolution. The Bolshevik coup and the establishment of what Delong calls “really-existing socialism” was not inevitable. Given Delong’s focus on the importance of individual policy decisions in the run-up to WWI and WWII, it would have been nice to mention that the relatively liberal and democratic Kerensky government vaporized its legitimacy by launching an ill-fated offensive against Germany in the summer of 1917 at the behest of its allies.

I was surprised that Delong used the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level to explain inflation in post-WWI France.

The section on the 1920s and the Great Depression gave too much credence to the Friedman-Schwartz view that the problem was tight monetary policy from the Federal Reserve, in my view. I would have preferred more of a discussion of the Eccles/Keynes/Kindleberger view that the problem was excessive debt, the imbalanced income distribution, and the decisions by the Bank of France and the Fed to sterilize gold inflows. Two related questions that I wish Delong had addressed:

Was the U.K. return to the gold standard in 1925 disastrous because the gold standard itself was bad, or because Churchill et al. chose the wrong price?

What would the 1920s have looked like if the Fed and the French had been willing to let gold inflows loosen domestic credit conditions and push up wages and prices, as they were “supposed” to under the classical gold standard? Unclear whether this would have been sufficient, but it should have made it easier for the major debtor countries to generate trade surpluses to service their wartime debts and reparations obligations.

Given Delong’s stated focus, I would have expected the chapter on WWII to highlight the Allies’ material advantages and describe how the war was won thanks to superior industrial organization and scientific prowess. I was expecting sections on the Manhattan Project, Bletchley Park, and a long discussion of other elements of the war effort that I am less familiar with. Instead, we mostly get a story about diplomacy, great leaders, and decisive battles. It’s entertaining, but struck me as a missed opportunity.

I also would have expected the ideas that Adam Tooze laid out so masterfully in The Wages of Destruction and The Deluge would have played a larger role in Delong’s narrative of the 1920s-1940s. Germany was technologically underdeveloped and resource-poor, which meant that any war had to be fought at high speed. Nazi cooperation with the Soviets until 1941 was not surprising, and began long before 1939 with joint military training and complementary trade relations. Both Hitler and Stalin were motivated by their hatred of the Anglo-American liberal order.

I wish the section on the Marshall Plan had mentioned the importance of the U.S. using currency aid to force the rest of western Europe—particularly France—to accept the reality that West Germany needed to reindustrialize and become economically integrated with its neighbors.

The section on postcolonial development (and the lack thereof) had a passage that confused me. Delong writes that “Low savings rates and the high cost of capital investment meant that the yield from a given savings effort in the global south was low” (348). Shouldn’t low savings rates and high cost of capital mean that there would be extremely high returns for any incremental saving? Later, Delong says that “each percentage point of total product saved led to less than half a percentage point’s worth of investment” (354-355). Where did the rest go? Net exports?

The section on the Shah’s economic reforms was really interesting and I wish there were even more on it, especially in contrast to Meiji Japan and/or Park Chung-Hee in South Korea. I was also surprised to learn that one of Khomeini’s original complaints was that the Shah’s land reforms were un-Islamic because they involved debt forgiveness.

I really liked this line (366):

There is no a priori reason to think that the economic organization best suited to inventing the industrial future should be the same as the one best suited to catching up to a known target.

Delong has a throwaway comment that the slowdown in productivity growth (as opposed to total growth) since 1970 could be explained in part by the fact that “energy diverted away from producing more and into producing cleaner would quickly show up in lower wage increases and profits” (431). I’m not sure I buy this but I would have appreciated more of an explanation either way.

The section on the 1980s was a bit odd. Delong writes that “big budget deficits soaked up financing that otherwise could have added to the capital stock” (443), but there is no explanation for how or why. Later he is more explicit, but it makes less sense (444-445):

After the US economy reattained the neighborhood of full employment in the mid-1980s, the Reagan deficits diverted about 4 percent of national income from investment into consumption spending: instead of flowing out of savers’ pockets through banks to companies that would buy and install machines, finance flowed out of savers’ pockets through banks into the government, it funded tax cuts for the rich, so the rich could then spend their windfalls on luxury consumption.

In fact, the U.S. private sector found it easier than ever to borrow in the 1980s thanks in large part to the boom in bank lending and the “high yield” corporate bond market, which is why private indebtedness exploded and why the decade ended with a miniature version of the balance sheet recession that would come again in 2007. The interesting story is that so much of this extra financing went into mergers, acquisitions, and leveraged buyouts—”the market for corporate control”—rather than additional capital investment.

Speaking of which: there is almost no discussion of financial history and financial innovation in Slouching, except at the very end in the context of 2008.

Finally, I would have liked more on this (453):

It is normal for a plutocratic elite, once formed, to use its political power to shape the economy to its own advantages. And it is normal for this to put a drag on economic growth. Rapid growth like that which occurred between 1945 and 1973, after all, requires creative destruction; and, because it is the plutocrats’ wealth that is being destroyed, they are unlikely to encourage it.

A different version of the book would have used this to frame a long discussion of antitrust and public choice theory. More generally, I would love to know the extent to which the post-1870 boom was due to the suppression of this “normal” behavior. If so, what caused that? And how can we restore the dynamism and competition that Schumpeter recognized was so essential for progress?

Delong’s equation is:

Value of the stock of ideas = average real income per person * (population ^ (1/2))

He uses the square root of population because it is halfway (in a geometric sense) between the unreasonable claim that additional humans have no value and the equally unreasonable claim that societies face no resource constraints whatsoever.

The exact number depends a lot on how exactly you define the international poverty line and how you account for differences in living costs across countries. The lowest estimate is that there are around 600 million people living in extreme poverty, while a slightly more expansive definition of material deprivation would run closer to 3-4 billion.

Hayek explained how markets could coordinate people all over the world to solve complex problems without any need for central direction, or even mutual awareness. He believed that the benefits of markets were so important that they needed to be protected from those who would impose plans or controls on the choices that individuals wanted to make, even if that meant using market institutions to restrain democratic decisionmaking.

Delong paints Hayek as a Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde whose insights into the power of markets were warped by his extremist libertarian views and his willingness to embrace dictators such as Pinochet, but I don’t think that’s really fair. In practice, the heirs to Hayek’s legacy are the men and women who run the European Union—which, not coincidentally, has often been described as the modern incarnation of the prosperous, tolerant, and multiethnic Habsburg Empire.

Hayek believed in guaranteed minimum incomes to protect against indigence and he arguably invented the Romneycare/Obamacare concept of mandatory health insurance. In fact, Hayek has been criticized by libertarians for being a socialist because, among other things, he believed in public provision of theaters and sporting grounds in addition to vital infrastructure, in using the government budget to run countercyclical macro policy, in military conscription (under certain conditions), and in public policies to protect against pandemics. Hayek’s biggest fear was the arbitrary use of state power, which was why he wanted governments constrained by clear general rules.

I know almost nothing about Polanyi’s thinking beyond Delong’s repeated claim that Polanyi believed that “markets were made for man, not man for the market”.

Pfizer developed its vaccine with BioNTech, which is based in Germany. But the underlying technology overwhelmingly derives from research going back decades that took place in the U.S.

Thanks for the review. A journalist friend told me it was a firing offense to quote from Yeat's Second Coming...but it sort of works!

Agree strongly with your first objection. From sentence #1, I was like, "okay, Solow growth model."

But "Solow" appears once in the whole book, and that's just in the notes, as an editor of a book containing a Delong chapter that's being cited.

I have a lot of issues with the Solow growth model (starting with the absence of market/pricing power, and the conflation of "capital" and "wealth" as synonyms), which I won't burden you with here.