Inflation In The *Very* Long Run

Broad-based price increases can smooth out difficult social adjustments. Climate change and population aging both have the potential to be inflationary if we fail to prepare in advance.

Earlier this year, I was commissioned by Vox to write an essay about what we have learned from the pandemic about inflation and how that might apply to the rest of the century. I am happy to report that the essay is now out and free to read. Please do check it out! What follows is a riff on the main argument, as well as some elaborations of points that proved to be a bit controversial.

My thesis was that inflation is often the least-worst economic response to social disruption. A broad increase in prices is an adjustment mechanism that can smooth out the financial consequences of large (and necessary) changes in relative prices.

Being helpful, however, is not the same thing as being inevitable. As I explain in the essay, inflation is about changes in nominal prices, which are ultimately a function of the interaction between nominal spending power—money, credit, incomes, asset prices, etc—and real production of goods and services.

There is no automatic link between changes in real variables—the unemployment rate, output, the relative size of the working-age population, how much of your country is under water or on fire—and changes in nominal prices. There must be some intermediate step(s) connecting the real world to the nominal one, which in turn are consequences of policy choices. Inflation is never inevitable, even if it can sometimes be desirable.

Here is how I put it for Vox:

Making sure there is just enough spending power to meet the needs of a growing and dynamic economy is much easier during periods of social stability. Business planning is not that hard if consumers want to keep buying roughly the same mix of goods and services every year and if the availability of raw materials, components, and workers rises in line with sales.

But mismatches between what businesses can produce and what consumers want create gluts of some things, shortages of others, and big changes in relative prices. The larger the mismatches and the faster they appear, the harder it is to adjust.

That’s precisely what we saw during the pandemic.

In theory, policymakers could avoid inflation in such scenarios by ensuring that prices fall enough in the out-of-favor categories to offset the price increases for in-demand goods and services. In practice, the government would have to engineer a bunch of price crashes at the same time as you have price spikes elsewhere. Even if that were possible, the results could be catastrophic, forcing large swathes of the economy into bankruptcy as incomes fell.

This is why economists agree that central banks should avoid overreacting to supply shocks. In practice, some additional inflation is preferable to the alternative because it allows the booming sectors to experience windfalls without immiserating the rest of the population. As the economists Veronica Guerrieri, Guido Lorenzoni, Ludwig Straub, and Iván Werning put it recently, “inflation is desirable … [because] relative price adjustment is more easily achieved through inflation in the expanding sector.”

That means that the best way to prevent inflation is to have a society that is flexible in general, while also being prepared for the big challenges that we know lie ahead. There are of course other ways to prevent inflation, such as running macroeconomic policy too tight, but they are worse.

There are many potential challenges one could think of. Last March I raised the possibility of “a global increase in capital spending to promote self-sufficiency (or at least supply chain resiliency) and to limit the risk of security-related disruptions”. As both proponents and opponents readily acknowledge, transitioning from a world that concentrates production of specific items in individual locales to a world with redundant capacity in many different places would be extremely expensive. I also raised the possibility of a persistent increase in global military spending.1 Rearranging what we make and how we make it would be disruptive, and a little inflation might help ease some of the pain of that disruption.

The Two Transitions

But the most obvious long-term challenges we will face between now and 2100 are the “green transition” (climate change and everything associated with that) and the “gray transition” (population aging and shrinkage in much of the world’s most productive societies).

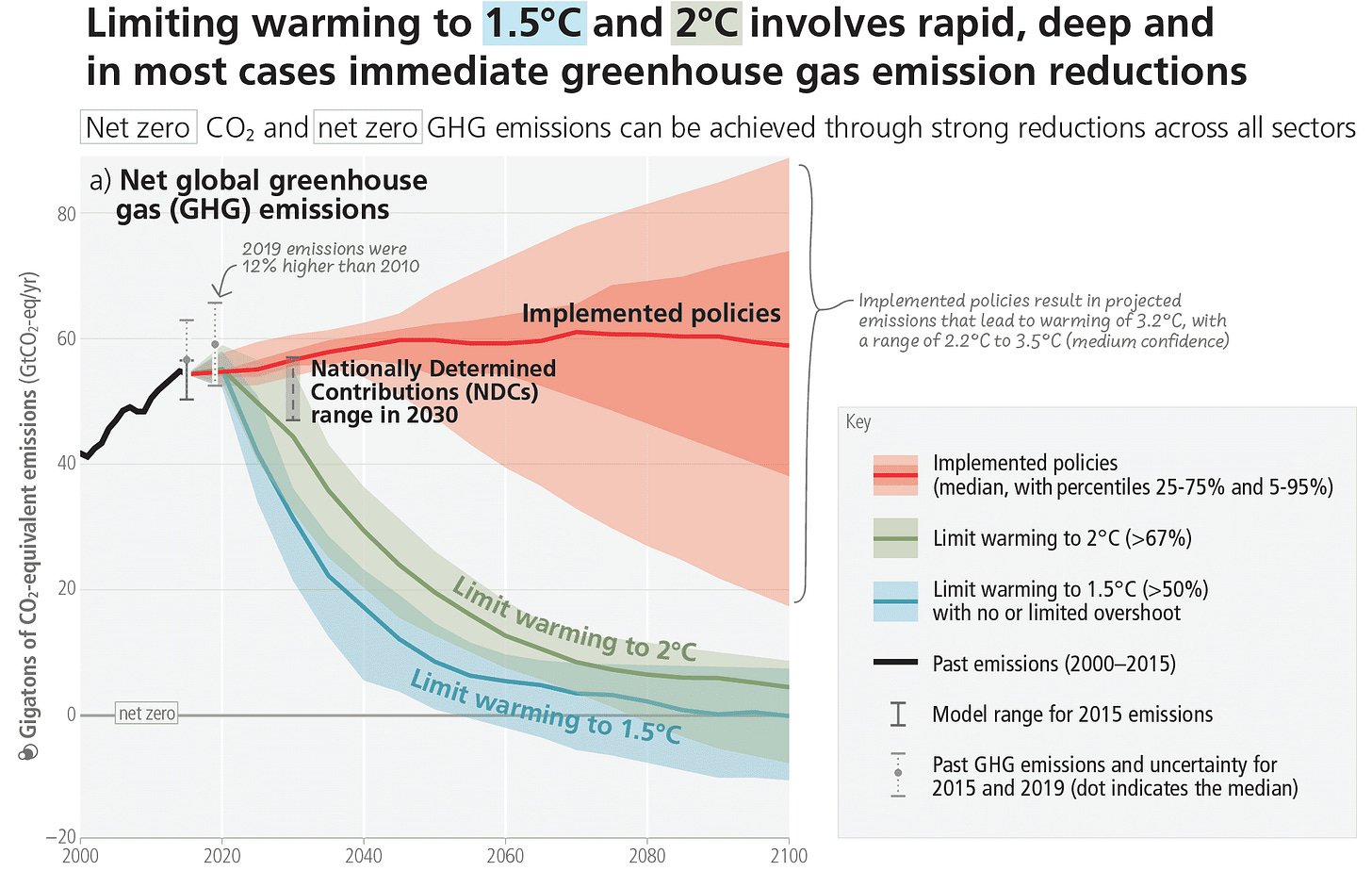

Consider the following projections from the the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. There are significant uncertainty bands that reflect reasonable scope for disagreement across different models and scenarios2, but what should be clear is that there is an inherent short-term conflict between “changing as little as possible how we produce and what we consume” (the red line) and “changing the physical environment as little as possible” (the blue line).3

From a longer-term perspective, of course, there is no tension at all. The potential changes to our physical environment that might occur if we followed the path implied by the red line could end up generating far more disruption to how we produce and consume than anything implied by following the blue line. In the words of the fictional Tancredi Falconeri, “if we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change”. The only real choice is between a managed transition and a chaotic one.

And the more chaotic, the more likely that some inflation could potentially prove helpful. As I put it at Vox:

Tens of millions of people employed in the fossil fuel sector globally will have to change jobs, and trillions of dollars of “stranded assets” — fossil fuel investments as well as investments in places that might become unlivable due to flooding or wildfire risk — will have to be written off. Incomes in fossil-dependent economies from Houston to Riyadh will fall relative to incomes in the rest of the world.

In this context, a bit of inflation can actually be good because it can allow for rapid growth in the booming clean energy sector without immiserating people due to the decline of fossil fuels. Since most mortgage payments are fixed, for example, rising dollar wages should at least prevent waves of defaults and foreclosures that would exacerbate the impact of decarbonization on exposed communities.

Inflation is not an inherent consequence of the green transition, or climate change more generally, but it could be desirable relative to the alternatives when thinking about how to distribute the financial costs of the real economic adjustment. From this perspective, the Inflation Reduction Act is an apt name for a program that is supposed to smooth the transition towards net zero greenhouse gas emissions.

The End of the Demographic Dividend

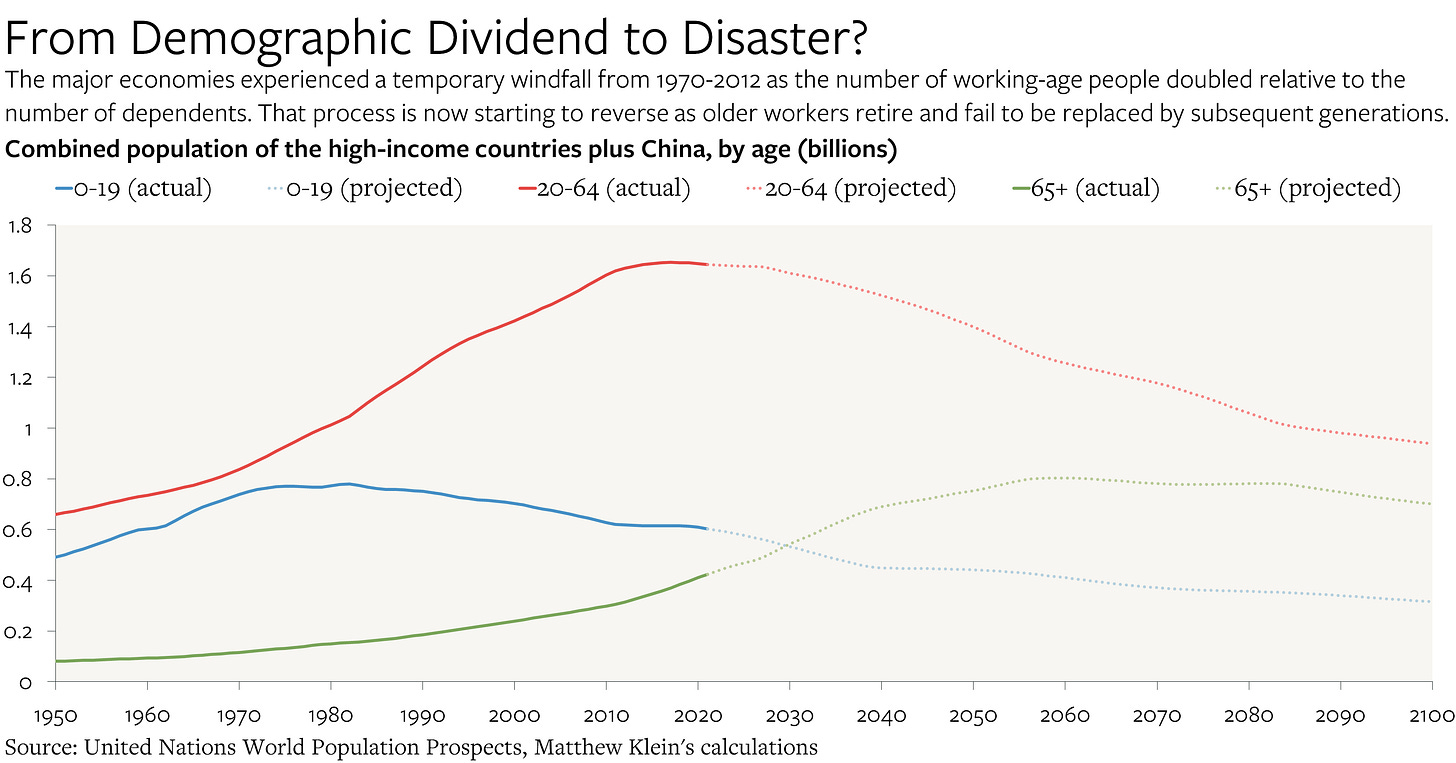

Similarly, consider the United Nations’ demographic projections presented in the chart below. Those projections may turn out to be wrong, but they are probably close enough to be useful for thinking about the future and the challenges ahead.

For as long as we have had reliable data, the overwhelming majority of global economic output has been produced in what the UN and World Bank call the “high-income countries”, plus China. And as can be seen in the chart above, the population of working-age people in those societies has already begun to fall, and is set to fall much further over the remainder of the century. This decline is not going to be evenly distributed—China is projected to lose 60% of its working-age population between now and the end of the century, while the U.S. working-age population is projected to rise (barely)—but the overall effect is going to be substantial.

After all, at any given point in time, everyone in a society is a consumer, but only some people are producers (the employed, basically). This is possible because the producers consume less on average than they produce and distribute the surplus to those who consume but do not produce (mostly children and retirees).4

Large changes in the ratio of net producers to net consumers therefore affect how much is available for everyone. Relatively more net producers creates a windfall that can support higher living standards, while an increase in net consumers does the reverse. Those changes can of course be offset by changes in productivity due to technological or process innovation, but the direction of the impulse is clear.

Will societies use inflation to help smooth out the costs associated with transitioning to a world where fewer people support more dependents? The limited historical evidence suggests that the answer could be “yes”, but I also hinted at why that experience might not be relevant:

Inflation tends to accelerate when workers have to support more non-working people, such as children and elderly people. Although historical evidence for this phenomenon so far is limited to baby booms, which fueled rapid expansions in the population of dependent children, it can give us a sense of what might happen when there’s an increase in the share of non-working seniors.

Some people (not unreasonably) took this to be an endorsement of the argument that Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan put forward in their book The Great Demographic Reversal, and in fact I did cite them in my Vox essay.

That might have been surprising to long-time readers, who might be familiar with my skepticism of demographics-based economic forecasts. About 7.5 years ago (!) I wrote a series of pieces at FT Alphaville in which I attempted to cast doubt on what was then being called the “Nangle/Goodhart thesis”, but which goes back at least to Alan Greenspan:

A Cautionary Tale of Relying on Demographic Projections (December 3, 2015)

How Much Do Demographics Really Matter? (December 7, 2015)

Aging, Real Rates, and Labour Bargaining Power: The Case of Japan (December 8, 2015)

Why Should Changes in Population Structure Affect Valuations? (December 11, 2015)

Do Demographics Dictate Lower Returns to Capital and Faster Inflation? (January 15, 2016)

I stand by what I wrote then—and I would encourage you to (re-)read those pieces if you have time—but I also think, having had the benefit of discussing some of these issues with Goodhart towards the end of last year, that it is worth clarifying where exactly it is we disagree, and where he agrees with me.