Inflation is Persistent and Consumers are Flush. Falling Rates Could be Dangerous.

Current income is already rising fast enough to finance broad price increases, with borrowing muted thanks to high rates. Lower rates could lead to massive wealth monetization and even more inflation.

The latest data on prices, wages, and household balance sheets argue against any meaningful change in Federal Reserve policy. With inflation continuing to run faster than target, with further price shocks likely to materialize, and with American households sitting on tens of trillions of dollars of untapped wealth, the risk is that any additional loosening of financial conditions would lead to a surge in spending that would magnify the otherwise modest impact of tariffs on the price level and create a self-reinforcing acceleration of price increases.

The Precarious Balance

There are three basic ways to finance spending1:

Current income, which at the economy-wide level is mostly equivalent to employee pay (because government benefits are mostly transfers from workers via tax receipts)

Selling assets (including spending down cash and equivalents)

Borrowing (creating liabilities, which are assets for someone else)

The past few years in the U.S. have been characterized by minimal private borrowing and relatively robust net asset accumulation, offset by robust government debt issuance2 and healthy (nominal) private income/spending growth. This netted out well in terms of real growth and financial stability, although the pace of nominal growth was about 1-1.5 percentage points too fast to be consistent with 2% yearly inflation.

Since the start of this year, however, the inflation outlook has worsened thanks to the the tariffs as well as the broader surge in policy uncertainty.3 The direct impact is probably not going to be that large, especially when compared to the massive shocks attributable to the pandemic, but it is nevertheless an impulse pushing against the “normalization” desperately hoped for by Federal Reserve officials and others. More importantly, the indirect effect on inflation could end up being much bigger if businesses believe that they have the opportunity to raise their prices by more than their input costs and if households have the financial wherewithal to accommodate those price hikes.

The danger is that American households have enormous untapped financial firepower at their disposal, which, so far, they have largely refrained from using. The goal for policymakers should be to keep interest rates high enough to discourage spending beyond what consumers can cover directly out of their incomes, while also encouraging them to spend less overall by keeping the returns from holding cash sufficiently compelling. This approach might not be sufficient to prevent an inflationary acceleration, because wage and price growth could still accelerate, but it is more prudent than lowering rates in an effort to goose spending even further.

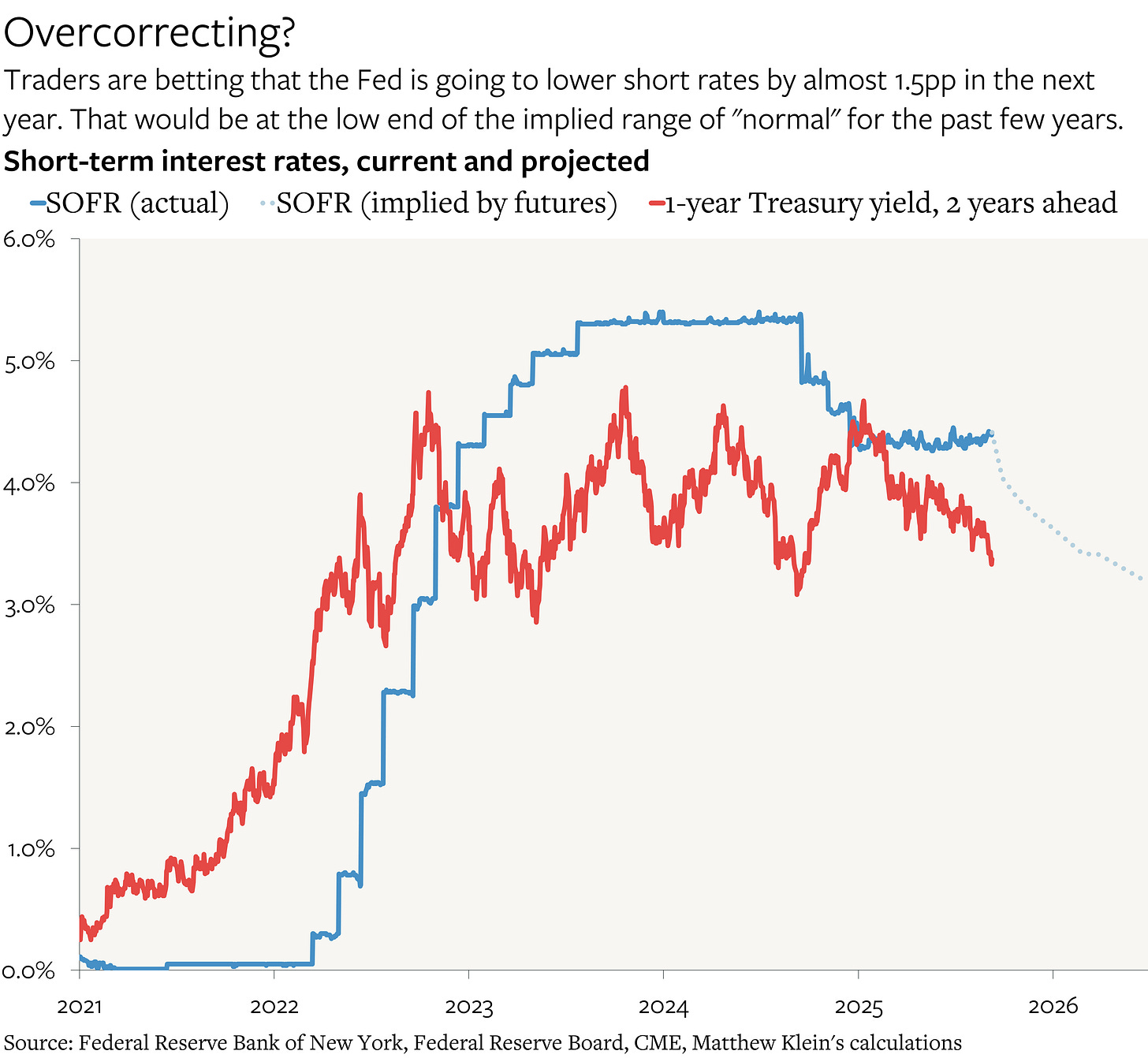

What is “high enough”? No one can answer this definitively, especially because there are many different borrowing costs that affect actual decisions and those costs are in part determined by beliefs about what will happen rather than anything that Fed officials are currently doing.4 Mortgage rates and corporate bond yields have both been trending lower over the past two years, with each down about 2 percentage points from the peak hit in October 2023. That looks quite a bit different from what has happened with short rates.

Even though some rates have already dropped from their cycle highs, they are still at levels that many Fed officials consider “restrictive”. Yet growth has nevertheless held up well throughout this period while underlying inflation had failed to decelerate over the past few years. That suggests that short rates should probably remain close to current levels even if there are quite a few cuts currently priced in. While small adjustments down—or up—might be warranted, the claim that “the neutral short-term interest rate” is closer to 3% than 4.5%, and that the Fed should move to “neutral” as quickly as possible, seems difficult to defend.

The rest of this note looks at the inflation and balance sheet data in more detail.