Inflation, Trump, and the Fed

There is no sane reason for the Fed to cut much, if at all. But the wannabe Erdogan (with a pinch of Nixon) has different ideas.

I have a new column at Semafor on Trump’s efforts to suborn the Federal Reserve. Check it out! Below is an expansion of some of the ideas I presented there, along with some charts. While my previous note on Türkiye was not directly about Trump and the Fed, it is nevertheless highly relevant.

The latest inflation, employment, income, and spending data all suggest that U.S. interest rates are just about right, if not too low, to keep the economy in balance.

So of course this is the time that President Trump has decided to ramp up his attacks on the Federal Reserve. According to Trump, Fed boss Jerome Powell is a “numbskull”, a “total and complete moron”, and “a stubborn mule” who is costing the government money by being “late” to lower interest rates, which are “at least 3 points too high”. Trump has drafted a letter firing Powell, who was nominated by Trump for the top job back in 2017, and claimed on Wednesday that many Republican lawmakers were supportive of the idea. Trump also claimed that he would not fire Powell “unless he has to leave for fraud, and it’s possible there’s fraud”.

That caveat is important. The Supreme Court ruled in May that the president had the right to fire officials at all independent agencies without cause except the Fed, supposedly because “the Federal Reserve is a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity that follows in the distinct historical tradition of the First and Second Banks of the United States.” Leave aside that the Fed was established in 1914 and has no link to the Second Bank of United States, which lost its federal charter in 1836. Ignore also that the Fed’s structure much more closely resembles the German empire’s Reichsbank, on which it was explicitly based, than anything created by Hamilton or his followers.

Still, the Supreme Court’s dubious historical and legal reasoning may help explain why Trump, along with some Republican Senators and assorted White House officials, including Ross Vought of the Office of Management and Budget and Bill Pulte of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, have recently pivoted to criticizing Powell over supposed cost overruns associated with the Federal Reserve’s long-planned building renovations. (Somewhat surprisingly, this critique seems to have started with a paper by Andrew Levin, who had been an advisor to Powell’s predecessor, Janet Yellen.) Firing “for cause” might be an easier case to win in the courts, although some Republicans are unenthusiastic.

The rest of this note looks at what is motivating Fed officials on one side and the administration on the other—as well as some (unpleasant) historical precedents for Trump’s attacks and what those precedents suggest might happen should the president succeed in suborning the central bank.

The Economic Case for Holding Interest Rates (More or Less) Steady

So far this year, through June, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) has been rising at a 2.5% yearly rate. That is an improvement from 2024 (2.9% 12-month change) and 2023 (3.3%) but, as I explained in a prior note, the apparent deceleration is almost entirely attributable to the predictable impact of the lagged slowdown in rent increases. Strip that out and the picture looks radically different.

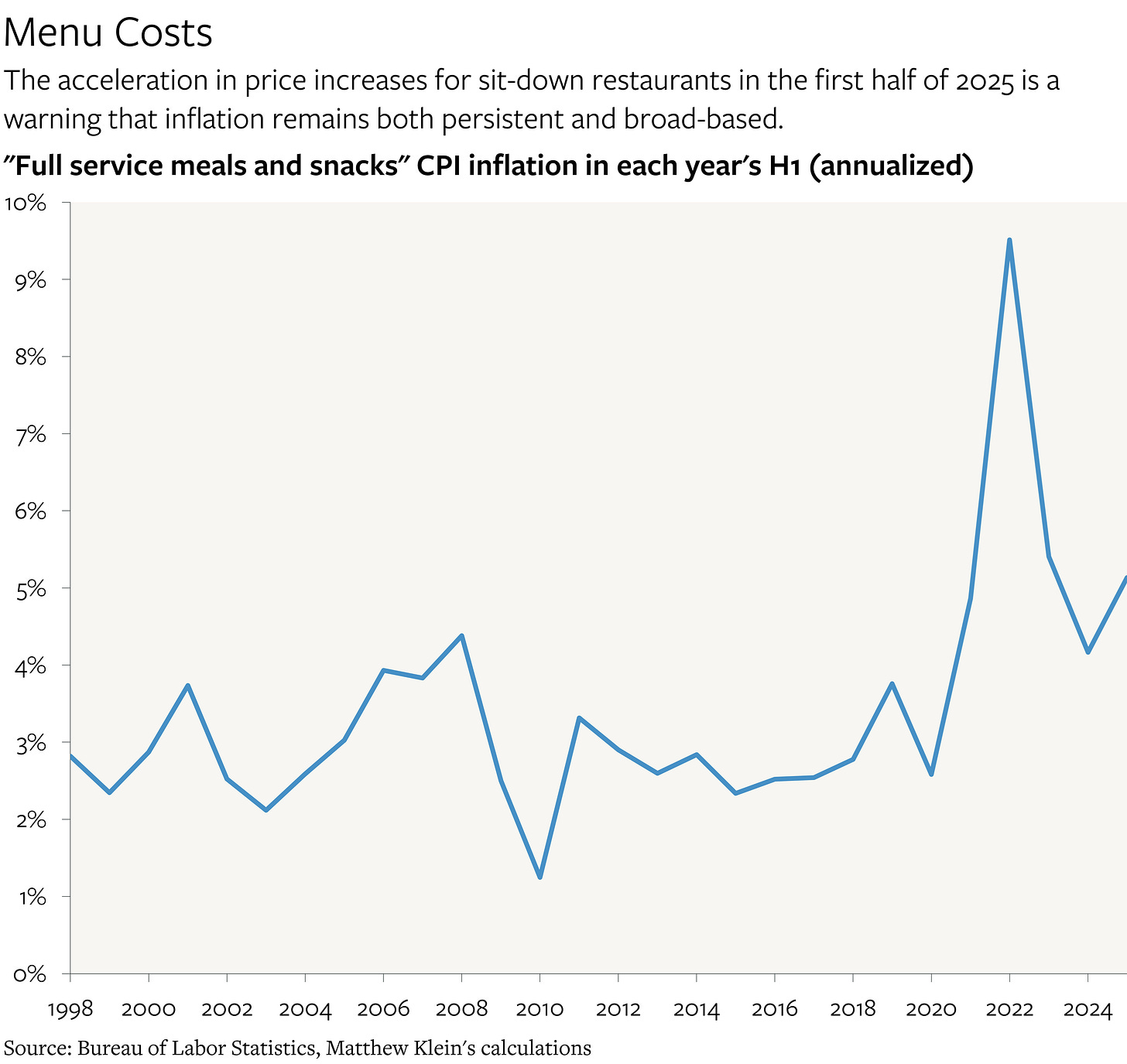

The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s measure of inflation based only on prices that change infrequently, excluding shelter, is 3% so far in 2025, which is the same as in 2023 and slightly faster than in 2024. Before the pandemic, this measure of inflation averaged around 1.8% a year. The Cleveland Fed’s 16% trimmed mean CPI, which excludes the biggest price increases and price decreases each month, rose at a yearly rate of 3.4% in 2025H1, compared to 3.2% in 2024 and 3.7% in 2023. That compares to 2.2% before the pandemic. And then there is the inflation at sit-down restaurants, which is the single best barometer of underlying inflationary pressures. So far in 2025, prices have risen at a yearly rate of 5.1%, compared to 2.8% before the pandemic. Even if this were somewhat exaggerated by seasonality, the price increase in 2025H1 is far faster than in 2024H1 (4.2% annualized) much less the pre-pandemic H1 average of 3%.

The simplest explanation is that nominal wage income is still rising about 1-1.5 percentage points faster than before the pandemic. That means somewhat more inflation relative to 2017-2019 as long as the bulk of this extra income is spent on goods and services, and as long as businesses have not magically improved their ability to ramp up production of goods and services significantly since the pandemic. Which of course is exactly what we have seen.