Managing Economic and Financial Entanglements With China

How to offset the impact of China's internal imbalances on employment, industrial capacity, and financial stability. Plus: how to maintain mutual interdependence without risking overdependence.

I recently had the chance to present my thoughts on “How Should the West Deal With China?” at the Centre for European Reform’s conference on “Europe and the Superpowers: The Rise of Economic Nationalism”. This note covers what I said, as well as some of the ensuing discussion.

I made two basic points1:

China’s internal economic and financial imbalances create challenges for the rest of the world, but policymakers in the major economies can shield their societies from (most of) the potential harms if they choose to do so. The trick is to use government borrowing and spending capacity to preserve private sector balance sheets, full employment, and the domestic industrial base.

The overwhelming dominance of Chinese producers in specific critical goods gives the Chinese government leverage over others. While this leverage is tempered by China’s own dependence on certain imports, the Chinese government is doing its best to create asymmetric dependence through a combination of self-sufficiency, diversification, and stockpiling. The democracies should learn from China’s approach by making their own societies more resilient while ensuring that China remains dependent on imported goods beyond just food and energy inputs.

What Happens in China Doesn’t Stay in China

Whether we like it or not, we are all connected. It is obvious that pandemics and the climate do not care about national borders, but our fates are also linked by trade and finance. Economic problems in one part of the world always end up having an impact elsewhere.2 If spending in a given society is persistently lower than the income generated there, spending in the rest of the world will have to run higher than income, with the difference covered by selling assets and/or borrowing.

Choices made far away can therefore create tradeoffs between domestic employment and indebtedness. Those tradeoffs can be managed to varying degrees, but most policymakers are not equipped to do so thanks to the limitations of orthodox economics.3

This was a major theme of Trade Wars Are Class Wars, which helped explain how China’s domestic political economy choices inadvertantly caused so much harm to many Americans and therefore contributed so much to the souring of U.S.-China relations. The book has the full account, but anyone interested in a shorter version can read what I wrote on the subject two years ago.

The very quick version is that China’s party-state responded to the tumult of 1989 by deliberately transferring as much spending power as possible from ordinary Chinese to businesses, foreign investors, and local governments. Squeezing consumer spending made it easy to build infrastructure, factories, and real estate quickly—and without having to rely on external finance.

While this may have made sense in the 1990s, the model has long outlived its usefulness. Investment grew rapidly, but was never sufficient to absorb the full value of Chinese production that was not consumed immediately. It turns out that the mechanisms developed to discourage consumer spending have proven to be more potent and more durable than their original rationale.4 This has suppressed total spending within China at the expense of Chinese consumers and producers in the rest of the world.

Put another way, China developed progressively larger trade surpluses. More and more of China’s output was exported abroad in exchange for nothing more than financial claims on non-Chinese. That was only possible because people in the rest of the world were willing and able to borrow more and more to finance their spending on imports from China in excess of the insufficient income they earned by selling goods and services to customers in China.

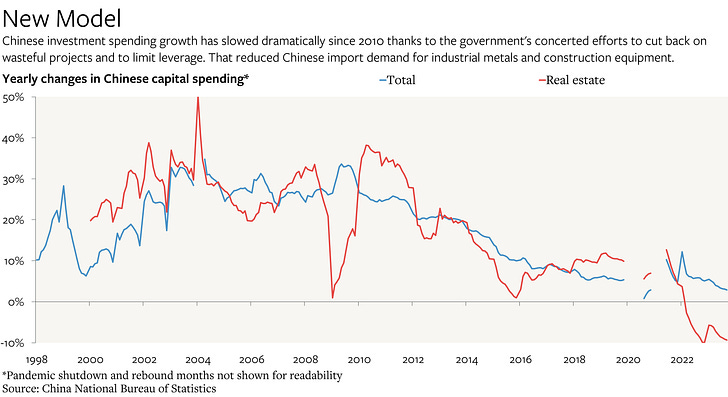

From China’s perspective, this process peaked in 2007-8. The global financial crisis limited Chinese businesses’ ability to rely on external demand, so the party-state responded by boosting domestic investment at the cost of soaring internal debt. By 2011 the consensus within China was that this had been a mistake, and the government progressively reduced the growth rate of investment spending from about 25-30% a year to less than 6% a year. (While also ramping up China’s ill-fated loans to poorer countries.)

The investment slowdown did not affect China’s external position—from China’s perspective—because it coincided with a slowdown in China’s overall growth rate. But China’s surplus in manufactured goods net of commodity imports has continued to grow relative to the economic output of China’s trade partners, thanks in large part to China’s growth relative to the rest of the world. Even though the value of Chinese exports fell in 2023, this has had no impact on China’s overall balance because the amount of money spent on imports is down as well.

The past few years have even seen a renewed surge in China’s surplus (properly measured) relative to China’s own GDP thanks to exceptionally weak growth in consumer spending and the sustained plunge in homebuilding.