Russia Was Prepared to Withstand Sanctions. Why Wasn't Europe Prepared to Impose Them?

It has been eight years since Russia last invaded Ukraine. What has changed, and what has not?

Russian exports of oil and natural gas are an essential source of hard currency that helps cover the cost of importing manufactured goods. Russia’s oil, gas, and coal exports are also an essential source of energy for European consumers and businesses, without which they couldn’t generate electricity, fuel their vehicles, or heat their homes and offices.

This entanglement limits the West’s ability to penalize Russian aggression financially. Yes, cutting Russia off from the global financial system would devastate the Russian economy and impose severe hardship on the Russian civilian population, but it would also force Europeans to slash their energy consumption.

Milder sanctions could protect Europe’s access to oil, coal, and gas, but their impact on the Russian government’s behavior would be commensurately smaller. The Putin regime has spent years acclimating Russians to material deprivation and it has also built up substantial financial buffers. Not for the first time, conservative macroeconomic and regulatory policies have shielded a revisionist regime from international pressure.

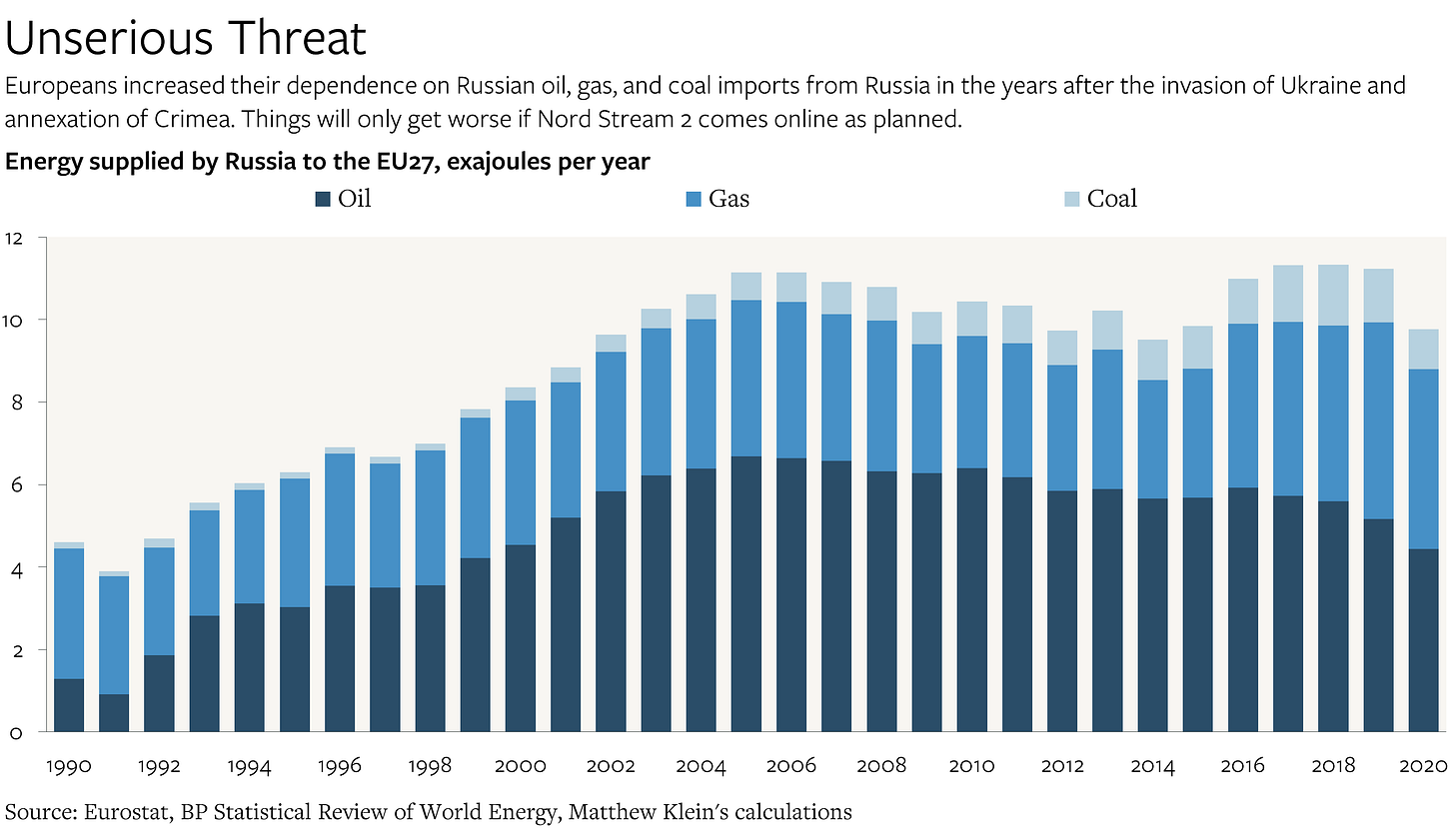

There was nothing that Europeans could have done about the Russian government’s decision to impose severe costs on its civilian population for the sake of maintaining its own flexibility. But Europeans can and should be blamed for becoming even more reliant on Russian fossil fuel exports since the 2014 invasion of Ukraine. They wasted nearly a decade when they could have been greening their economies and also increasing the security of their own neighborhood. Ukrainians—and others—will now have to live with the consequences.

Russia’s Fortress Balance Sheet

The Russian government’s ability to withstand financial pressure was hard-earned. Most obviously, total spending on imported goods and services (in U.S. dollar terms) has consistently been about 25-30% lower than it was before the first invasion of Ukraine. While some of this can be attributed to declines in the world prices of Russia’s oil and gas exports, Western sanctions and Russian domestic policies have also played a role.

The sustained drop in imports has left a mark on Russian consumers’ spending. In inflation-adjusted terms, Russian households spent 12% less in 2016 than they did at the peak in 2014. Even in 2019—before the coronavirus pandemic upended the world economy—Russian consumers were about 2% worse off in material terms than they were before the first invasion of Ukraine.

Meanwhile, Russian businesses and other borrowers responded to external financial pressures—and domestic political ones—by slashing their foreign-currency denominated debt by $200 billion since the beginning of 2014. The Russian government also spent $200 billion adding to its stockpile of reserves (gold, bank deposits, and bonds) since mid-2015.

The net effect is that Russia’s central bank now has enough foreign exchange reserves ($630 billion as of last month) to cover 2021 spending on imports ($368 billion) plus 75% of the country’s entire stock of foreign-currency denominated debt ($353 billion as of 2021Q3).

Much of that debt isn’t even due for at least two years.

None of this, however, is sufficient to protect Russia from the impact of sustained Western sanctions. As the Taliban has discovered, foreign reserves are useless if your counterparties freeze your accounts. Even Russia’s $132 billion in gold reserves couldn’t be used to settle payments if Western banks were banned from touching anything involving Russia.

The Russian government nevertheless feels that it has room to act because it knows that the Europeans need them.

Europe’s Self-Inflicted Error

Shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2014, I wrote that Russia faced a long-term strategic vulnerability: Europeans had the option to squeeze Russia permanently by reducing their reliance on Russian energy exports. At the time, about 60% of Russia’s total export revenues came from sales of crude oil, refined products, and natural gas—and much of that went to Europe.

The Europeans could have built out their capacity to import liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the U.S. and other allies. Even better, the Europeans could have reduced their reliance on fossil fuels altogether by building out more alternative energy generation.

Either way, Gazprom’s network of pipelines would have been transformed from a source of leverage into an albatross. Russia could have found other customers for its gas—most obviously China—but building the necessary transportation infrastructure to compensate for the loss of the European market would take years. Russian oil could be sold elsewhere more easily, but the prices would have to be lower if European demand disappeared.

At first glance, it almost looks as if that’s what happened. Russia’s total export revenues from oil and gas fell from $350 billion/year before the first invasion of Ukraine to $231 billion in 2019. While Russians made up the difference by increasing other exports, including food, the squeeze on energy revenues is real.

But the Russian energy export squeeze had nothing to do with European restraint.

In 2013, the countries of the European Union imported about 135 billion cubic meters of natural gas from Russia. That was equivalent to about 70% of Russia’s total gas exports and equal to 37% of the EU’s worldwide gas imports. Yet in 2019, EU countries imported 166 billion cubic meters of Russian gas—23% more than before the invasion of Ukraine. That was equivalent to 75% of Russia’s total gas exports and 38% of the EU’s worldwide gas imports in 2019.1

European demand for Russian crude oil and refined petroleum products was slightly lower in 2019 than in 2013, but this was offset by surging European demand for Russian coal, which now accounts for almost half of the EU’s coal imports. Put another way, the countries of the EU went from consuming about 62 exajoules of energy in 2013 to 61 exajoules in 2019, while Russia went from supplying 10 exajoules of that energy in 2013 to 11 exajoules in 2019. Despite a slight decline in fossil fuel demand, Russia’s share of the European energy mix rose from 16.5% to 18.5% after the invasion of Ukraine. Europe’s dependence will only increase if the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline comes onstream as planned.

The perverse result is that Europe is at greater risk of Russian pressure than the other way around. Natural gas prices in Europe are now about 5-6 times as high as in the U.S. because Gazprom has been withholding supply and because the lack of LNG terminals has prevented ships from moving gas across the Atlantic.

And while Europeans have made some modest investments in solar and wind energy over the past decade, it hasn’t been nearly enough to make a dent in the overall energy mix, especially after factoring in the impact of the decisions to decommission existing nuclear power plants.

The Europeans seem to have—belatedly—realized the implications of all this. As EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen put it on Tuesday:

This crisis shows that Europe is still too dependent on Russian gas. We have to diversify our supplies…We will have to massively invest in renewable energy…because this is a strategic investment in our energy independence.

I hope her words are heeded.

We don’t yet have full data for 2021, while the 2020 data are distorted by the collapse in energy demand due to the pandemic.

Great articles. This raises so many more questions. Why is it that Authoritarian govts (Russia/China) better at geopolitics than democratic govts? - Is it because it helps to have a time horizon greater than 4 years in an increasingly low growth, uncertain world with large imbalances? - Is this why Authoritarianism is on the rise across the world? - Are western democracies, tired of fickless responses going to turn to authoritarian leaders as a show of power?