Russia's Industrialization and WWI

Some thoughts on Tooze featuring Listian political economy, cross-border financial flows, and railway routes

History is about understanding why things happened the way they did. Listing events in a coherent sequence isn’t enough; the historian also has to explain why different chains of events didn’t happen.

That thought nagged me while reading the last paragraph of this passage in an excellent recent piece from Adam Tooze on the origins of World War I1:

The military-industrial race that directly impelled the outbreak of war in 1914 was not naval but continental and it was not, in fact, one race, but two. The decisive axis was France-Germany-Russia. This revolved around the relative mobilization of national resources by France and Germany and the sporadic and unpredictable development of Russia.

Russia was truly the swing variable. Russia was defeated by Japan in 1905 and had been shaken by revolution. On the other hand its huge size and enormous potential made it a looming threat as far as Germany and Austria were concerned…For progressives in France and Britain, those who believed most firmly in the logic of progress, it was profoundly disturbing to find themselves from the 1890s onwards, drifting towards a strategic alliance with Tsarist Russia…But the demands from French Republicans and Russian radicals were, in fact, to no avail.

The international system had its own compulsive logic that might be modified but could not so easily be overridden by political considerations, however important they might be. The consequences of Bismarck’s revolution of 1866–1871 could not be so easily escaped. By the 1890s the triumphant consolidation of the German nation-state had created enormous pressure for the formation of a balancing power bloc anchored by France and Russia.

To oversimplify, Tooze describes the buildup to the war as a situation where French liberals desperate for security against a supposedly aggressive Germany gradually reconciled themselves to allying with Tsarist Russia, which in turn made Germans of all stripes increasingly terrified of being outflanked by an adversary that was growing rapidly. For many Germans, their only option was to strike first. (Or, more precisely, to induce Russia to start a war before it was ready.)

For Tooze, the geopolitical dynamics were ultimately a consequence of changing material circumstances: “uneven economic development threatened to shift the military balance of power, by way of manpower, tax revenue and technological capacity as well as strategic assets like railways”.

“Combined and uneven development”

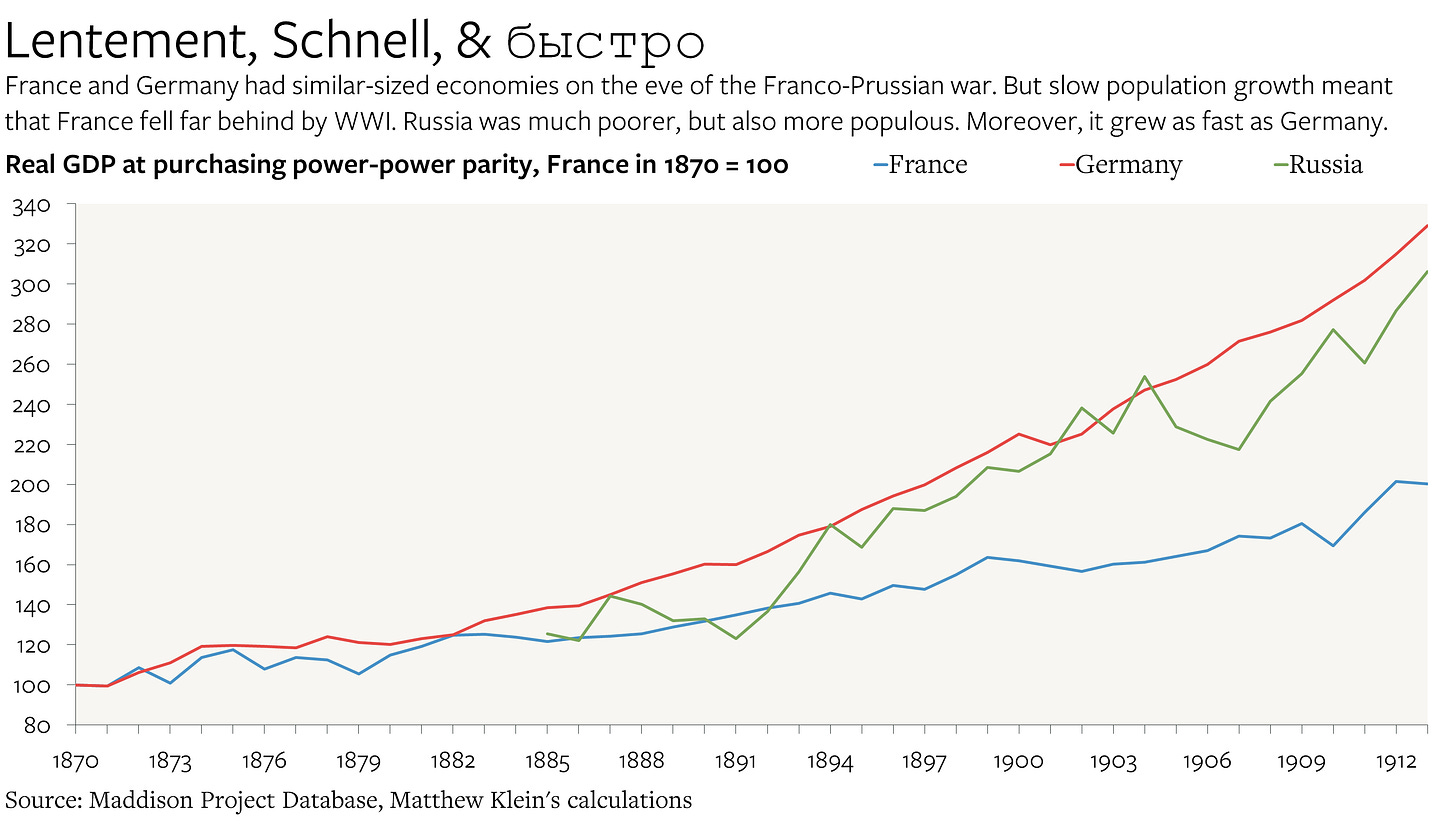

Data from the Maddison Project Database bear this out. The German economy went from being about the same size as the French economy on the eve of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) to being 50% larger by 1903 to being 64% larger by 1913.

This wasn’t due to faster growth in income per person in Germany, since output per head was almost identical in both countries throughout 1870-1913. Instead, the GDP divergence was attributable to much faster population growth in Germany (1.2% each year on average) compared to France (just 0.2% a year).2

The Russian Empire was much poorer than either France or Germany, but it had a much larger population, which meant that its economy had long been comparable in size to the other two major continental European powers.3 Moreover, both Russia’s population and its average income were growing at the same rapid rates as in Germany.

So while France was getting left further and further behind by a rising Germany, an alliance with dynamic Russia could theoretically help compensate for that weakness. The corollary was that Germany’s strong economic base would never be sufficient to guarantee its security against revanchist France as long as France could supplement its own forces with the Russian army.

This is a compelling narrative that fits the facts. But it also leaves us with some big unanswered questions about the origins of the war and whether it reasonably could have been avoided.4 What follows is my attempt to address one of those questions. In particular, I want to try to explain why Russia’s growth was threatening to Germany.

We should not assume that the Franco-Russian alliance was inevitable. It’s reasonably clear why France would want to ally with Russia—to avenge the losses of 1871—but it’s much less clear why Russia would want to ally with France instead of Germany, its traditional partner. Russo-German antagonism might seem like the natural state of affairs when looking back with hindsight from the vantage point of the 21st century, but it wouldn’t have seemed natural at all in 1880.

As it happens, Tooze and I discussed some of these issues on a podcast hosted by our mutual friend Jordan Schneider. You can listen to our conversation about it in minutes 18:00-22:00.

I’m happy to present a much more complete answer below. It involves everything from the relative yields on French and German investments to one Russian policymaker’s admiration of Friedrich List.