Solving One Puzzle in U.S. GDP Data (Maybe), Finding More

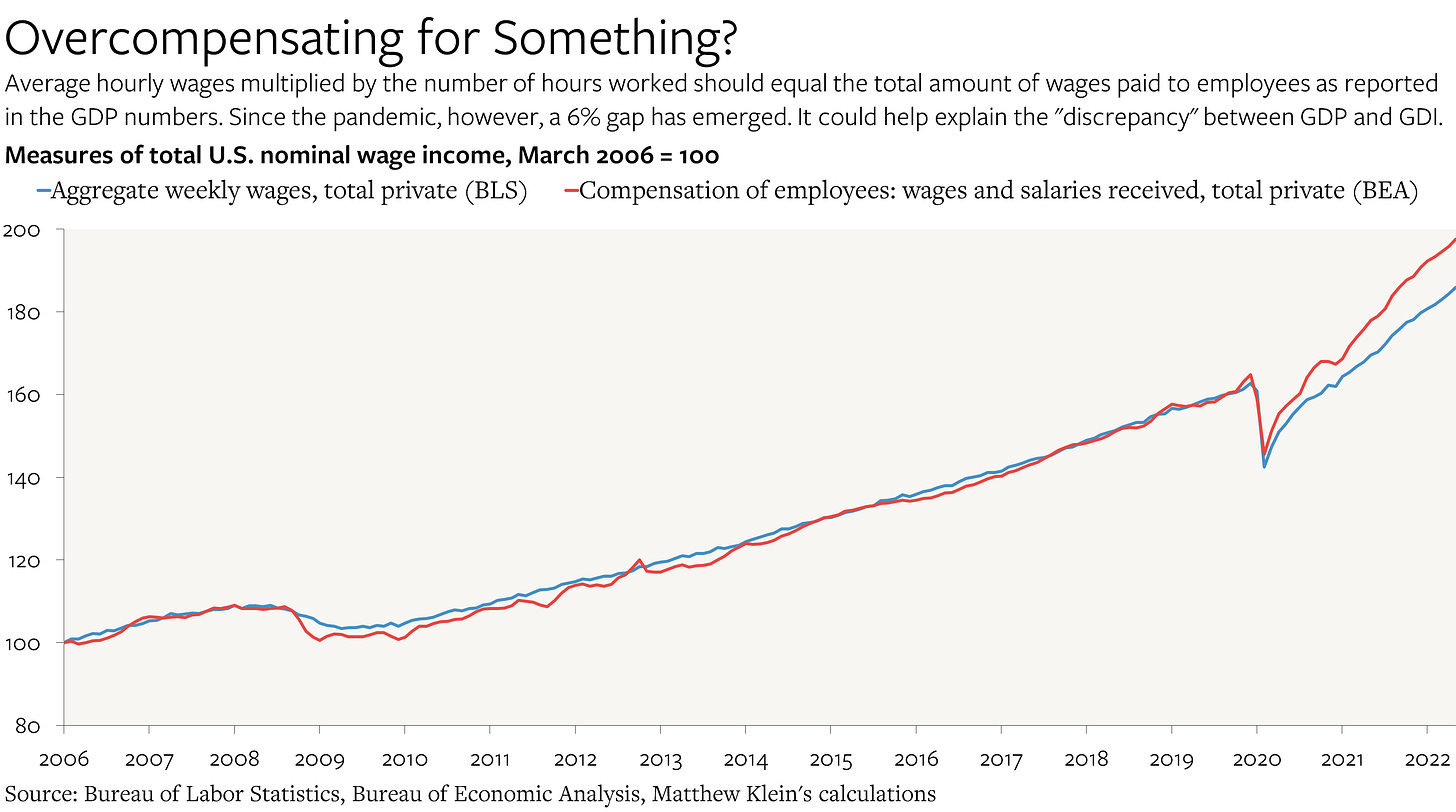

Private-sector wages may be overstated by 6%. While that would close much of the "statistical discrepancy" between GDP and GDI, it leaves many other questions open.

The measured value of the goods and services produced in the U.S. and the reported income generated in the U.S. should be the same. Yet the “statistical discrepancy” between domestic income and domestic production just keeps getting wider and wider. As of 2022Q2, Gross Domestic Income (GDI) was 4% higher than Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Domestic income net of depreciation (NDI) was 5% higher than Net Domestic Product (NDP). That is far beyond the historic norm. It also means that we don’t know whether the U.S. economy has been shrinking or growing.

There are only three possible explanations:

Incomes have been overstated and will be revised lower (and the economy peaked in 2021Q4)

Production has been undercounted and will be revised higher (no downturn in 2022H1)

Incomes have been overstated and production has been undercounted

Until recently, I was completely convinced that the income numbers were right and that the production numbers were too low. I still lean in that direction, but I am less sure about it now than I was a week ago. There is a compelling case that the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) has been overstating private-sector wage incomes. However, while that would explain much of the discrepancy between GDI and GDP, plugging in the “corrected” numbers raises several new questions.

To be clear: I have nothing but respect for the people who work at the BEA. Their experts are generous with their time and incredibly helpful at answering questions. The organization of the data on their website is better than anything I have encountered anywhere else in the U.S. government or in other countries/international institutions. This note should be not be read as a criticism of these public servants. But I still have a lot of questions about what’s going on.

Why I Thought The Income Numbers Were Right

I have been bothered by the statistical discrepancy since January, back when the latest available numbers were from 2021Q3. The BEA has warned that capital gains and losses are sometimes wrongly counted as corporate profits and proprietors’ income. But the discrepancy between domestic income and domestic production looked just as large even when those hard-to-measure components were excluded from NDI. Reconciling the gap between income and production with business income alone implied that earnings had collapsed far below pre-pandemic levels—and that was totally inconsistent with what companies were reporting and with tax data.

I soon began to suspect that the BEA may have been inadvertantly excluding some forms of business investment spending from the GDP numbers by misclassifying capex as consumption of intermediate inputs. That hypothesis helped explain some inconsistencies in the data on foreign trade, inventory accumulation, and manufacturing output that started showing up in 2022Q1. As time went on and more data were released, it became increasingly difficult for me to believe that the economy was shrinking in the first half of this year. It was particularly difficult to believe that U.S. GDP was shrinking in the ways that the BEA was describing.

My assumption was that the other components of domestic income—most notably employee pay—weren’t susceptible to the kinds of measurement errors that might explain the discrepancy. It had not occurred to me that the BEA would run into problems estimating wages and benefits because the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is constantly publishing and revising detailed data every month.

Why the Income Numbers Might Get Revised Down

But that assumption turned out to be wrong. As Seth Ackerman pointed out to me last week, there has been a growing disconnect between the BLS measure of private-sector wages and salaries and the BEA equivalent since the start of the pandemic. The BEA’s estimate of total wage earnings has been running 6% ahead of the BLS version since January 2022, although the gap has come down slightly from the peak in March.