The 6% Solution?

U.S. spending and incomes continue to grow a bit faster than before the pandemic. And that's okay.

I would suggest a criterion for choosing a monetary framework, when we next choose one, should be that it is a framework that contemplates enough room to respond to a recession. In other words, it should foresee nominal interest rates in the range of 5 percent in normal times. How that is achieved seems to me to be a question of second-order importance…I have never seen a calculation of the costs of running say 3 rather than 2 percent inflation that are terribly large…If I had to choose one framework today, I would choose a nominal GDP target of 5 to 6 percent.

—”Why the Fed needs a new monetary policy framework”, Larry Summers (June 7, 2018)

I do not know what Federal Reserve officials thought of Summers’s argument when he published it in 2018. But one could be forgiven for thinking that his views have guided their actions in the years since. The latest batch of data for 2024Q1 confirm that, whether by accident or by design, the U.S. economy remains settled in the stable ~5.5-6% yearly nominal growth trend it has occupied since mid-2022.1

And Fed officials seem pretty happy with this outcome. (As they should be!)

Despite the “lack of further progress” towards their 2% yearly inflation goal, Fed boss Jerome Powell made clear at the latest press conference that it is “unlikely that the next policy rate move will be a hike.” The debate is still about when it will be time to lower rates, not whether higher interest rates will be necessary. While he repeated the dubious claim that policy is “restrictive,”2 Powell also noted that “we have the luxury of strong growth and a strong labor market,” which explained the lack of urgency about future rate cuts.

In other words, the revealed preference of most Fed officials is that they seem to want to keep nominal spending and incomes chugging along more or less as they have been since mid-2022. Political sensitivities about inflation mean that they will not come out and say this explicitly, but it would be the simplest explanation of what we have seen. A few weeks ago, I recorded an interview where I made this point.

The data only tell us what has already happened, rather than what will happen, but even so, it is striking how consistent the data have been across a range of frequencies.

The Labor Market’s New Normal?

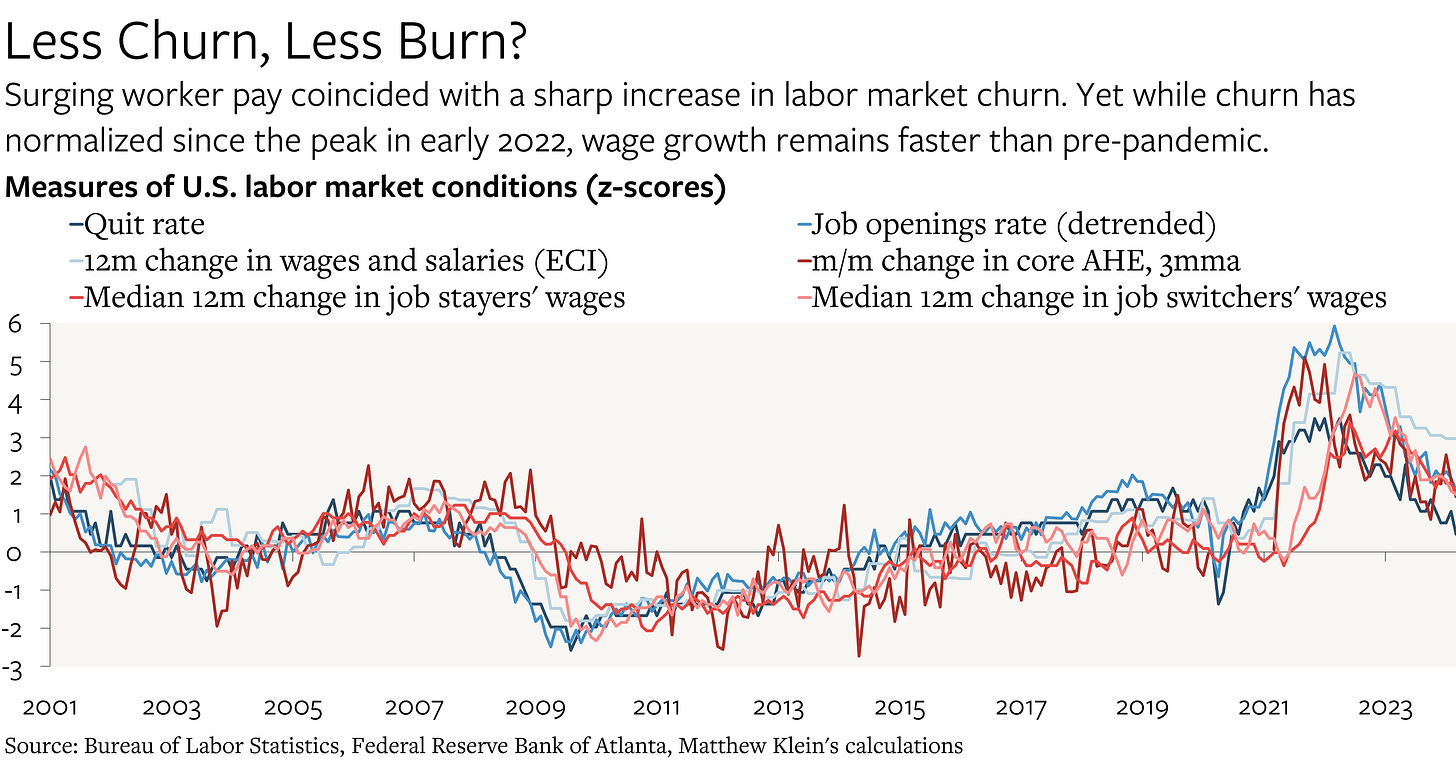

This week gave us updated measures of job market churn (JOLTS), as well as the detailed fixed-composition estimates of worker pay by industry, occupation, and unionization (ECI). The data remain consistent with what has been evident for the past year or so: while the number of unfilled openings has come down, the number of workers leaving their jobs for better prospects has come down, and the rate at which employers hire new workers has come down, wage growth remains persistently faster than it did before pandemic, even if it has slowed somewhat from the peak in 2021.

The first chart shows a broad range of measures individually, while the second chart consolidates things into three lines. The normalization of job churn seems to have had much more of an impact on the wage bump from switching jobs (back to where it was before the pandemic) than on the underlying trend in pay growth (still about two standard deviations faster than the 2018-2019 average).