The Case for 38 Million More U.S. Jobs by 2031

Overcoming the soft bigotry of low expectations.

We have been living below our means for a long time. That’s largely a choice by policymakers who worry that having “too many” people gainfully employed would lead to excessive consumer price inflation.1 One consequence is that tens of millions of people who want to work, produce, and earn income are instead jobless—with all of the poverty and other socal ills that often entails.

A new paper from J.W. Mason, Mike Konczal, and Lauren Melodia of the Roosevelt Institute attempts to quantify just how many potential workers are being left behind, or, alternatively, how many more adults the U.S. economy could productively employ if there were sufficient demand for labor. Their answer: a decade of robust economic growth alone could generate more than additional 38 million jobs compared to current levels by 2031.

That’s a big number—about 28 million more jobs than the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is expecting ten years from now. It’s based on an estimate of what Mason et al. call America’s “latent labor force.” As they put it:

Instead of thinking of a hard line between “in the labor force” and “not in the labor force,” we can imagine a slope or gradient between people who can be hired most easily, to groups progressively farther away, who can be drawn into employment but only over time and with friction. This friction includes not only higher wages (and prices, to the extent that wage costs can be passed on by employers) but also changes in the way workers are recruited and trained, the way work is organized, and adjustment by workers themselves. As strong demand is sustained, workers further from employment can be drawn into the labor force. In effect, a sustained boom progressively converts the latent labor force into the current labor force.

The rest of their paper is about how to model this.

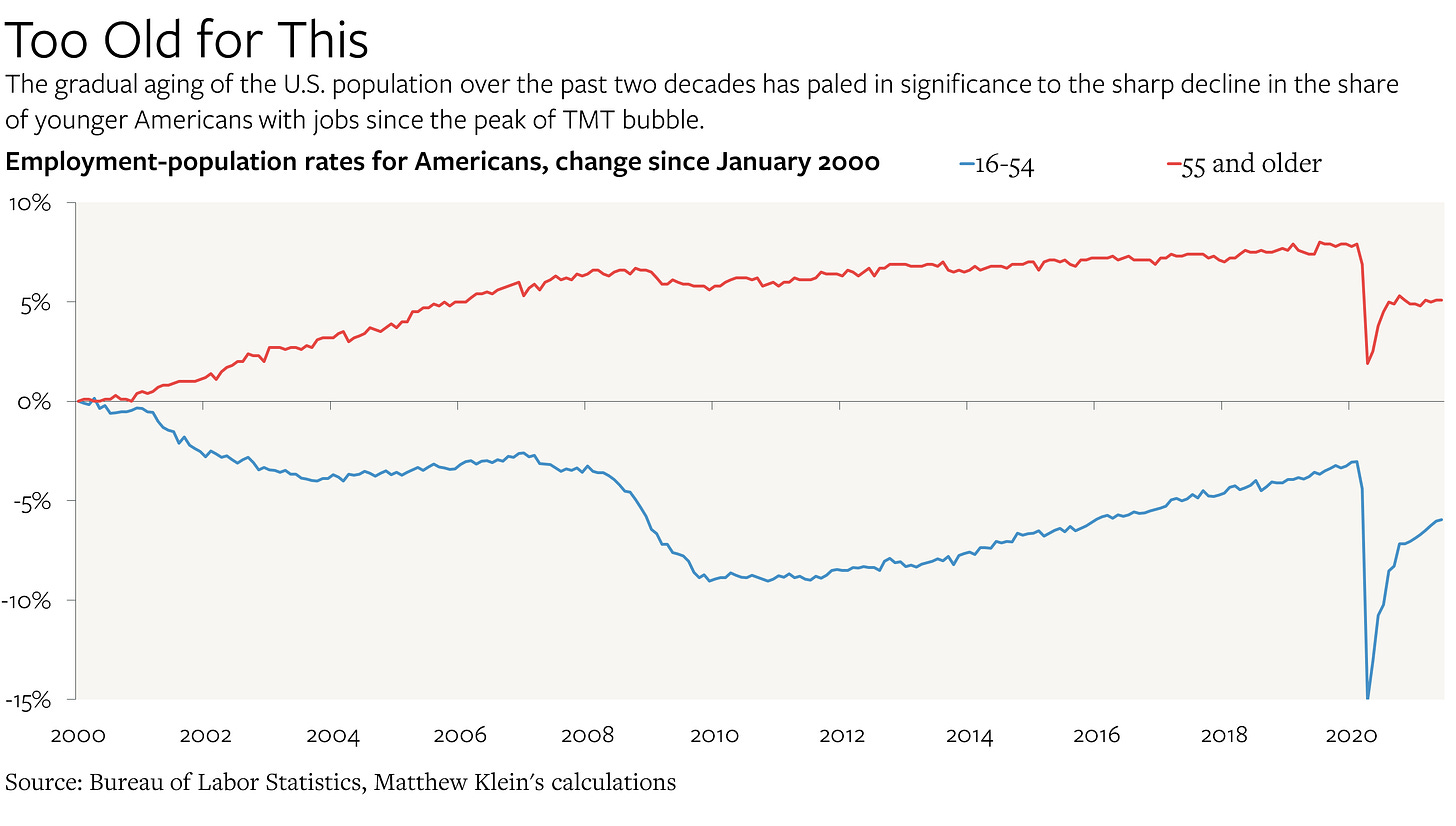

Their first step is to note that population aging fails to explain (or predict) much of anything. After all, the decline in America’s total employment-population ratio since 2000 is almost identical to the drop in the employment rate for Americans aged 16-54 over the same time period. That’s becauase the growth of the elderly cohort was more than offset by the sharp increase in employment rates for Americans aged 55 and older, from just over 30% in the late 1990s to just under 40% by the eve of the pandemic.

As they put it:

Given that the decline in overall employment rates over the past 20 years was dominated by changes within age groups, it cannot straightforwardly be the result of an aging population. And indeed, claims that depressed employment was a purely demographic phenomenon in the slow recovery following 2009 turned out to be wrong…In 2014, the CBO predicted, consistent with the demographic story, that paid employment in 2019 would be 145 million. In fact, it was 151 million.

Their second insight is that there are large gaps in the share of Americans with jobs based on race, gender, educational attainment, and disability status—and that these gaps fluctuate systematically based on economic conditions. That suggests that prolonged periods of rapid growth would help close the gaps across various demographic groups. Yet standard models are predicated on the idea that differences in employment rates reflect “structural” factors rather than businesses’ total demand for workers and the relative bargaining power of employers.

This is particularly noticeable when it comes to race, with a tight relationship between the age-adjusted Black-White employment gap and the overall level of the U.S. unemployment rate. From the paper:

But it’s generally true for a wide variety of other categories. While there are many factors depressing the share of American women who work outside the home, for example, Mason et al. make the important point that addressing those problems wouldn’t be sufficient by themselves to lift female employment without a supportive macro environment:

If the goal is to close the gap between men’s and women’s employment rates via some mix of changing social norms and better support for families’ caregiving needs, it will be necessary to achieve fast enough employment growth to absorb the additional women workers entering the labor market. Making it easier for women with young children or other caregiving responsibilities to work will not increase employment unless there is also enough demand to create jobs for them.

Putting these ideas together, Mason et al. start with a simple demographic forecast of the U.S. population based on age, race, gender, and education. Then they see what happens if each age cohort were to return to its prior maximum employment rate, which for most working-age Americans last occurred in the late 1990s. That would lift the 2031 U.S. employment rate by 2 percentage points, from 58% to 60%.

Then they imagine what would happen if non-White Americans of different ages, genders, and educational backgrounds were just as likely to be employed as their White counterparts. That lifts the 2031 employment rate by another 2 points, from 60% to 62%.

Next, they imagine what happens if the gender employment gap were to close, with the caveat that both male and female parents of young children would have relatively lower employment rates than other Americans of the same age. That would lift the 2031 national employment rate from 62% to 66%.

Finally, they consider what would happen if the gap in employment between college graduates and Americans without 4-year degrees shrank to its narrowest historical level, which pushes up the 2031 employment rate from 66% to 68%. For perspective, the national employment rate peaked at 65% in 2000 back when the population was younger and the economy was much stronger than it has been ever since.

The net effect:

By 2031, our estimate of potential employment reaches 190 million, about 28 million more than estimated by the [Congressional Budget Office]…Our preferred estimate of the potential employment rate is about 10 points higher than the CBO’s.

In chart form:

How to get from here to there? Steady growth in the number of jobs between now and then of a little more than 2% a year. That’s ambitious, but not unreasonable. As they put it (in a manner that should be familiar to readers of The Overshoot):

This is the rate of employment growth we would expect from a boom strong enough to reverse the post-2007 demand shortfall…By the end of 2020, real GDP per capita was about 16 percent below the level one would have predicted based on the earlier trend…If real GDP per capita were to catch up to the earlier trend over a 10-year period, that would imply (given projected population growth) annual growth in real GDP of about 5 percent. With 2 percent annual employment growth, this would require 3 percent annual productivity growth, comparable to the late 1990s.

Let’s see what we can do.

The basic idea is that a) more people working means more income to spend on goods and services and b) fewer jobless workers means existing employees have bargaining power to raise wages and therefore business costs. Put a) and b) together and you supposedly get higher prices and higher wages mutually reinforcing each other in an inflationary process. Assuming that’s ever actually happened, it would have last occurred in the 1970s. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell memorably dismissed the concept as “one of the old formulas” at his June 16 press conference. For a longer treatment of the question, you can read this and this.