The Covid Recovery Looks Different Now

The BEA has updated its estimates of everything from private sector wages to spending at restaurants and dividend payouts.

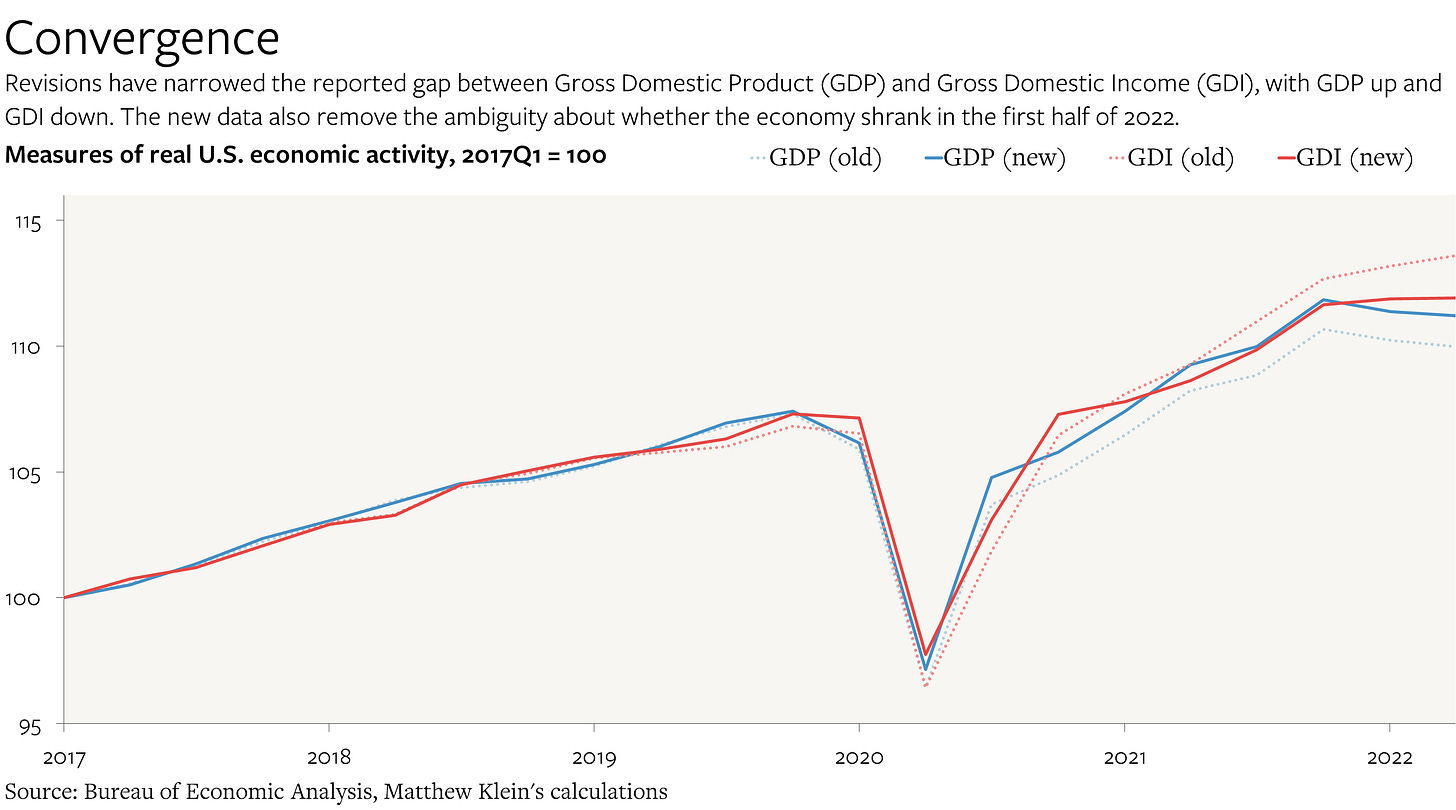

The latest revisions from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) have closed most of the gap between the reported value of the goods and services produced in the United States and the income ostensibly generated in the U.S.

Before the most recent updates, Gross Domestic Income (GDI) in 2022Q2 was supposedly 4% higher than Gross Domestic Product (GDP). These two figures should be identical—if measured correctly. Subtracting depreciation made the reported gap even larger, with Net Domestic Income (NDI) 5% higher than Net Domestic Product (NDP). The good news is that, as of this writing, revisions have shrunk the “statistical discrepancy” to 1.3% of GDP and to 1.5% of NDP. After accounting for inflation, the level of GDP as of 2022Q2 has been revised up by 1.1% (NDP is unchanged), while the level of real GDI has been revised down by 1.5% (NDI is down 1.7%).

The guts of the revisions are where things get interesting. The main highlights:

Private-sector wages and salaries were revised down by 2%. (I warned about something like this happening last month.)

Consumer spending was revised up, with particularly large revisions to sectors that were hit hardest by the pandemic.

While total estimates of after-tax profits were essentially unchanged, the split between dividend distributions and everything else (retained earnings and buybacks) was radically altered, with significant implications for the savings/investment balance of the corporate sector, as well as the composition of household income.

Most inflation measures were unchanged, but there were a few notable exceptions.

The trade deficit was revised down thanks to higher estimates of U.S. exports of services to the rest of the world.

Business investment on equipment was revised much lower, to the point that there has supposedly been no growth since the peak in mid-2019. (I’m not sure I believe this, but I flagged the possibility back in May.)

At the same time, some things weren’t revised, which means there are still unexplained phenomena in the data. The strange surge in real imports of durable goods in 2022Q1, which ostensibly implied that domestic production fell so hard that the U.S. economy went into a downturn, remains on the books. The revisions to the household saving numbers aren’t (currently) consistent with the Federal Reserve’s separate estimates. And productivity—real GDP per hour worked—is still falling at an unprecedented rate, which seems odd.