The Curious Case of Australia's (Brief?) Current Account Surplus

For decades, Australians spent more than they generated in income, raising finance from abroad to make up the difference. That has reversed dramatically since the end of 2017. But will it last?

Australia is a rich English-speaking country with secure property rights and relative openness to inflows of people and investment from abroad. These qualities have long made Australian assets appealing to everyone from reserve managers to those looking for second homes (and residency rights in case of emergency). Combined with Australia’s robust population growth and its large, capital-intensive mining sector, it is unsurprising that Australians have long spent more than they earned, covering the difference with external finance: Australia’s current account deficit averaged 4.3% of gross domestic product from 1981 through 2017.

Yet the past few years have been different. By the eve of the pandemic, Australia’s current account deficit had moved into surplus for the first time since the early 1970s, while net exports hit their highest value on record relative to GDP. In the years that followed, the newfound trade and current account surpluses surged even further—and while both have receded somewhat as of 2024Q1, they are still unusual relative to the post-1980 history.

Most of the swing in the current account balance since 2017 is attributable to the shift in the trade balance. So what changed?

Understanding Australia’s Trade Balance

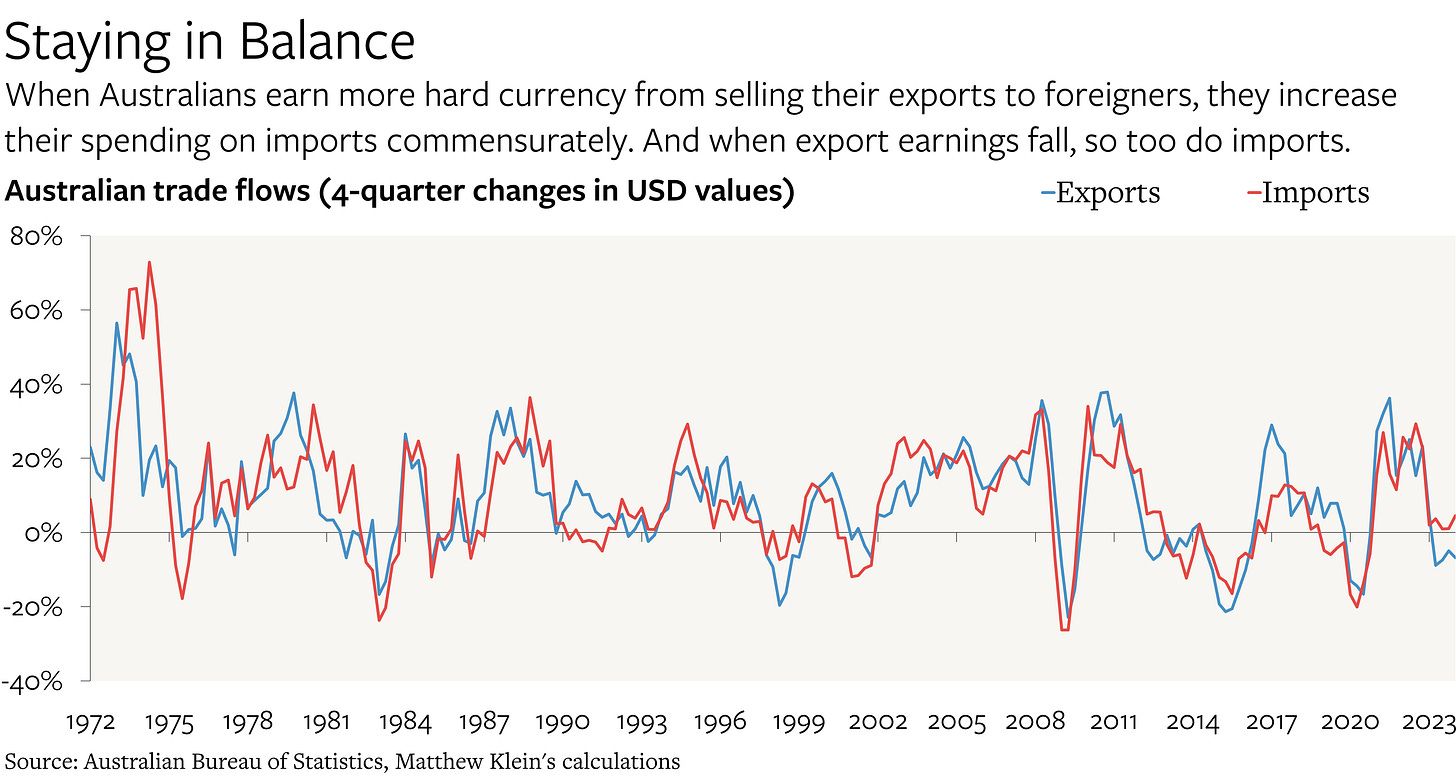

Australian (nominal) export earnings and Australian spending on imports tend to move together.1

But while changes in nominal import spending closely track changes in real import volumes, the same cannot be said for exports. Instead, changes in nominal earnings consistently dwarf the modest changes in real volumes.

Australia’s main exports are iron ore, coal, other metals and ores such as aluminium, copper, and gold, natural gas, and “education related personal travel”. With the exception of foreign student spending, these export earnings are much more volatile than export volumes, with the difference attributable to the volatility of industrial commodity prices. (The notable exception was the pandemic, which led to a crash in foreign students and tourists coming to Australia.)

Historically, the mining companies that generate the bulk of Australia’s export earnings responded to changes in prices by adjusting their investment. This is what the textbooks say should happen, hence the old saying that “the cure for high prices is high prices”. The extra investment led to a surge in imports of materials and equipment, which limited the impact of higher commodity prices on the overall trade balance. Changes in relative prices transfer purchasing power from buyers to sellers, but Australian miners had offset the impact by using that extra purchasing power to increase their own spending. This meant that higher iron ore prices were relatively benign from the perspective of global employment and incomes, unlike higher oil prices in the pre-shale era.2

The past twenty years have defied this pattern.