The "Easy Disinflation" Is (Mostly) Over. The Fed Grapples With What Comes Next.

Commodity prices have fallen from their peaks and stabilized, manufactured goods price dynamics have normalized, and measured rental inflation is set to slow. But core wage growth has yet to budge.

We have got to get inflation behind us. I wish there were a painless way to do that. There isn’t…We have to get supply and demand back into alignment, and the way we do that is by slowing the economy.

—Jerome Powell, September 21, 2022

I would almost say that the conditions that we need to see in place to get inflation down are coming into place…the process of that actually working on inflation is going to take some time.

—Jerome Powell, June 14, 2023

U.S. inflation peaked last summer and has since decelerated from around 10% annualized in February-June 2022 to ~3% since November 2022.1 Meanwhile, the U.S. economy has added around 3.5 million jobs since June 2022—including 2 million full-time positions—while the unemployment rate has held steady at the lowest rate since the 1960s.2 From this perspective, immaculate disinflation has already been achieved: price growth normalized even though no significant costs were imposed on the broader economy.

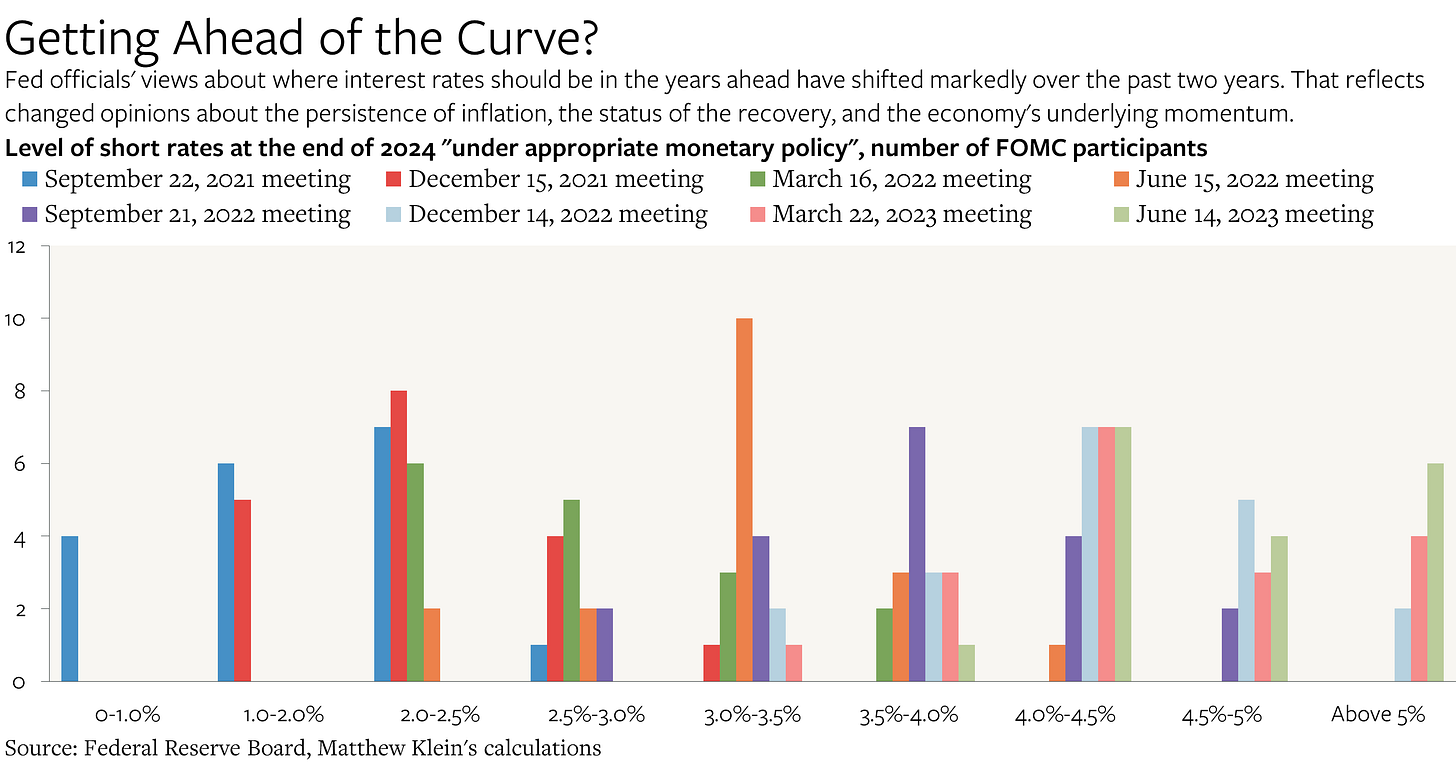

But Federal Reserve officials disagree. All but two members of the Open Market Committee believe that they will need to raise the target band of short-term interest rates from current levels (5-5.25%) by the end of this year “under appropriate monetary policy”. Twelve believe that the policy band will need to rise at least 0.5 percentage points from where it is now. And while most Fed officials hope to lower nominal rates from that elevated level in 2024 and 2025, that is only because they also hope that inflation will slow enough such that real interest rates are roughly stable. Their aspiration is “a continuing loosening in labor market conditions”, as Fed boss Jerome Powell put it at the most recent press conference, and the median Fed official expects that this will eventually push up the jobless rate by about 1 percentage point.

The problem for the Fed is that the disinflation that has already occurred mostly reflects the one-off unwinding of temporary disruptions. Grocery prices have stabilized after rising 15% a year, energy prices are down almost 20%, the prices of many manufactured goods that had been affected by production and distribution issues have either stopped rising or fallen slightly, and contracted rents on renewing leases have finally caught up with rental rates advertised on vacant units.3 Many businesses’ input costs, which soared so much in 2021H2-2022H2, are lower now than they were a year ago.

But what happens after these favorable impulses have run their course? There are good reasons to believe that the U.S. economy’s underlying inflation remains stubbornly ~2 percentage points faster than the Fed’s 2% yearly target.

The consumers most likely to buy things—workers4—are continuing to experience faster wage growth than in prior decades even as businesses’ ability to boost output of goods and services remains stuck in the slow productivity trend of the 2010s. Unless that dynamic changes—or workers collectively somehow end up spending less of what they are paid on goods, services, or housing—the mismatch will generate more inflation than Fed officials say they want. And if those officials eventually decide that they are unwilling to squeeze out the last couple of percentage points of inflation at the expense of American workers, many longer-term yields (except maybe mortgages) are probably too low.

What follows is an update of the indicators I track to get a sense of U.S. inflationary pressures, with a focus on charts. I encourage you to read my note from last month for more context for my interpretations of these data.