The NY Fed Trading Desk's Time to Shine?

The most interesting paper from the latest Jackson Hole Economic Symposium suggests that central banks should think harder about managing market conditions in sovereign debt securities.

Hiring professionals makes sense for jobs you literally cannot do yourself (surgery), as well as for jobs where the monetary cost is less than the time and discomfort involved if you were to do it yourself, such as (for me) home renovation projects. Otherwise, if you want something done right at a good price, you should just do it yourself.

Central bankers, government debt managers, and financial regulators should remember this when thinking about their relationship with the securities dealers that make markets in sovereign bonds.

While private sector intermediaries often do a good job of matching buyers with sellers even as they risk their own equity to squeeze out pricing irregularities, when it really counts, broker-dealers have been unwilling—or unable—to do what they are supposed to do. Instead of stabilizing markets, they have exacerbated volatility. Central banks’ trading desks should therefore be more active in making markets and establishing pricing bands for government debt directly. From this perspective, the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) recent experience might be a model for the rest of the world.

The Covid Yield Surprise

The failure of the dealers to do their job was particularly evident in March 2020, when yields on sovereign bonds in both the U.S. and Europe spiked despite a worsening economic outlook. Real yields on Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS) jumped by more than 1 percentage point in the span of a week.

Nominal yields moved by much less, but nevertheless went in the wrong direction (up) relative to what would have been expected for assets that are supposed to be negatively correlated to the growth outlook.

Analysts at the time were quick to identify what had happened. Entities that were strapped for cash during the worst of the panic—mutual funds, hedge funds, and foreign reserve managers—sold bonds in size. That forced many relative value hedge funds, which had eked out profits in 2018-2019 by levering up Treasurys while selling offsetting Treasury futures, to liquidate their positions. (Interestingly, that trade seems to have returned, which may explain the massive recent surge in Treasury purchases attributed to “households and nonprofit institutions”.)

In theory, the forced selling should have been a great opportunity for profit-maximizing securities dealers to step in and buy. Except that they didn’t, which forced prices down and worsened trading conditions even as volumes soared.

That was a serious problem. For savers, the entire point of government bonds is that they promise positive nominal returns over time and move inversely to risky assets during downturns. When they work, bonds are valuable diversifiers that allow savers to take more risk in the rest of their portfolios.1 But what happens if government bonds no longer work as advertised?

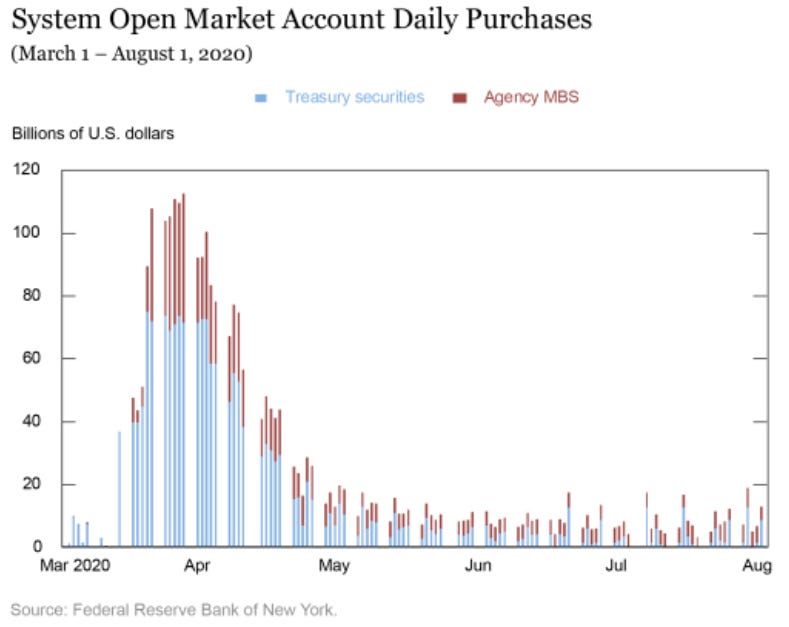

The Federal Reserve responded by buying bonds in size. On March 16, the Fed bought about $40 billion of U.S. Treasurys, another $40 billion on March 17, then $45 billion on March 18, $75 billion each weekday from March 19 through April 1, $60 billion on both April 2 and April 3, and then gradually tapered daily purchases to $10 billion/day by the end of April before establishing a more “normal” monthly schedule. The net result was ~$1.5 trillion of UST purchases in six weeks. In addition, the Fed spent ~$600 billion buying mortgage bonds backed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae (agency MBS) in March and April, which was supposed to help reduce convexity risk and therefore interest rate volatility/premiums for all borrowers.

Other central banks, including the Bank of England, the Bank of Canada, and the European Central Bank, did similar interventions. According to the Bank for International Settlements, which recently published a comprehensive overview covering most major economies, the largest increases in central bank balance sheets relative to national income occurred in Japan, the euro area, the U.K., Israel, Hungary, Australia, New Zealand, and then the U.S. Purchases of government debt specifically were largest in the U.K., New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and then the U.S. and euro area.

The bond-buying worked—insofar as yields came back down—but the whole experience was sufficiently unpleasant that officials around the world have devoted years to figuring out how to avoid repeating it ever again. At least in March 2020 there was no contradiction between purchases that supported “market functioning” and the desired monetary policy stance of the major central banks. By contrast, the Bank of England’s experience last September of being forced to buy bonds right after it had committed to selling bonds was a warning about what could happen in different conditions.

Deregulate the Dealers?

Thus, just last week, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City hosted Darrell Duffie and Jeremy Stein to discuss the subject at the latest Jackson Hole Economic Symposium. (Theirs were the most interesting set of papers at this year’s symposium, at least as far as I am concerned.) Both agreed that contraints on dealers were a serious problem that prevented them from stepping up to buy bonds, and that some of those constraints were attributable to regulatory choices that might be worth revising.

But there is an alternative approach, which both Duffie and Stein hinted at, even though neither seemed particularly keen on it: the central bank could disintermediate the dealers and play a more active role in directly making markets and setting bond prices across the yield curve. The BOJ already provides an example of how this could work in practice.