The Russia Sanctions Need a Reset

The oil price cap is reducing federal budget revenues but is not having an impact on government spending or Russia's ability to import goods from the rest of the world. The allies must correct course.

For the past 18 months, the global alliance of democracies has supported the Ukrainian war effort by tilting the material balance against the Russians.

The allies have helped the Ukrainians import (some of) what they need by providing financial assistance to the Ukrainian government and by donating existing supplies of military hardware. While there is always room for improvement, this aid has been essential.

At the same time, the allies have attempted to prevent the Russians from importing what they need with export controls and financial sanctions. In theory, this should have been a potent weapon. As I put it last April:

While it would be inappropriate for NATO aircraft to bomb Russian tank factories, shipyards, and missile assembly plants today, it would also be unnecessary. The democracies can replicate the effect of well-targeted bombing runs with the right set of sanctions precisely because the Russian military depends on imported equipment from the very same set of countries it has angered with its brutal attack on Ukraine.

This did not happen. The Russian military remains extremely dependent on imported parts, components, machinery, and software from the rich democracies—yet it continues to get much of what it needs.

After cratering in the first few months of the war, Russia’s imports of manufactured goods rebounded by the end of last year and have held steady since then. While rising exports from China explains some of this, most of the rebound in Russian imports can be attributed to exports from the democracies that have been routed through third countries—as I have been pointing out for almost a year. Businesses in Europe, Japan, the U.S., and other jurisdictions that have publicly committed to helping the Ukrainians are effectively contributing to the Russian war effort. The measures undertaken so far, including the oil price cap imposed at the start of 2023, have failed to prevent this. Something new must be done.

The State of Russia’s Imports

The Russian government initially responded to the sanctions by restricting the data that it published, particularly its monthly data on imports of manufactured goods. I got around this by aggregating data from a broad sample of exporters that had consistently accounted for about 74% of Russia’s pre-war goods imports.1 (My initial research was cited in a front page story in the New York Times, among other places.)

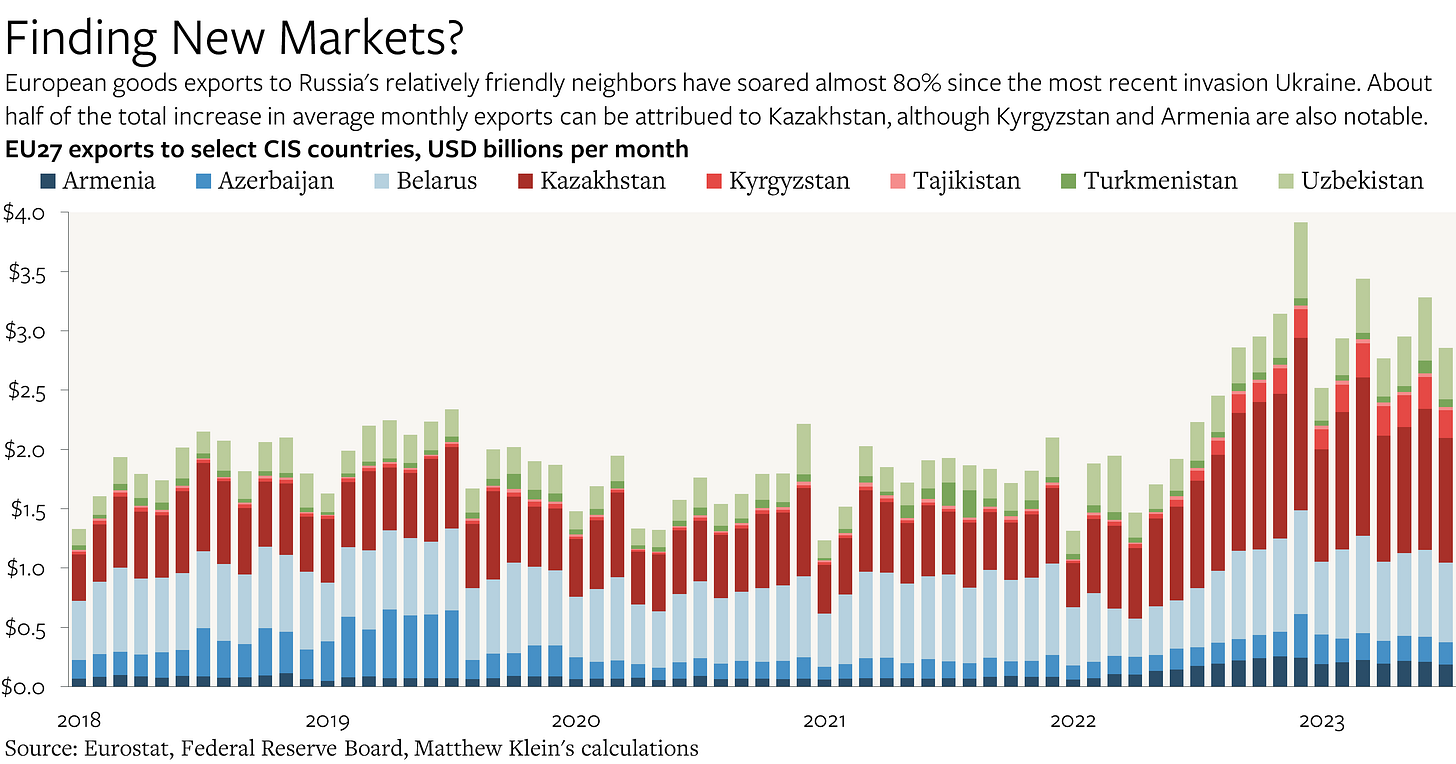

As time went on, I discovered that many of the world’s leading manufacturing powers—most notably the EU—were exporting far more to Russia’s friendly neighbors in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) than before, and that this export surge seemed to correspond to an export surge from CIS countries to Russia. Adding in an estimate of the “excess exports” to my estimate of Russian imports suggested that Russian imports had recovered much more than I had previously believed.

Then the Russians decided that they no longer needed to keep things secret. As of this writing, the Bank of Russia is once again publishing monthly data on exports and imports of goods, although they are no longer providing a breakdown between CIS and non-CIS countries. Similarly, the Ministry of Finance, which had also blocked foreigners from accessing monthly budget data, now regularly updates its figures on tax revenues, spending, and borrowing across all levels of the Russian government. It turns out that Russia’s official monthly import numbers and monthly import tax receipts correspond almost exactly with my estimates based on data from Russia’s trading partners, after adjusting for the CIS countries.

This is a serious problem. It is also absurd, since so much of the exports going to Russia are coming from the allied democracies. These include sophisticated machine tools that are necessary for cutting metal into artillery rounds.

I will leave it to the lawyers and technical experts to determine how exactly the existing controls should be adjusted. But it should be clear that the current situation needs fixing. (I would also encourage policymakers to remember the suggestion I made at the start of the war to provide compensation to companies that stand to lose business as a result of the sanctions.)

Oil Sanctions Confusions

Since the war began, many well-meaning people argued for extreme sanctions on Russian exports of crude oil, refined products, and natural gas. The thinking was that, since the Russian government gets a large chunk of its tax revenues from those export industries, a boycott would make it hard for the Putin regime to pay for the war.

There were always two problems with this argument (beyond the potential impact on world oil prices if total demand did not fall and Russian output were not redirected elsewhere).

First, the Russian government does not literally pay for anything using oil and gas. Instead, Russians are paid in rubles, which the government prints, while foreigners are paid in dollars or other hard currencies. The rubles work as payment to the extent that they can be exchanged for goods and services that people actually want. Similarly, the hard currency is valuable only if it can actually be used. In both cases, the real constraint on Russian government spending is the state’s ability to tap the resources of productive societies, mostly via imports. (The Russian domestic economy is technologically unsophisticated, although labor can be compelled.)

Before the war, oil and gas revenues were helpful because people in Europe and Asia were happy to offer goods and services in exchange for Russian energy. That meant that Russian energy exports had economic value inside Russia. But if many of the producers of equipment and components were no longer willing or able to sell anything to Russian buyers because of sanctions or export controls, Russian energy revenues would no longer be as valuable regardless of how many dollars were theoretically being generated and taxed.

Ultimately what always mattered was access to imports. Had Russians been unable to import, oil sanctions would have been unnecessary. But since Russians can import, the oil sanctions are relatively ineffective.

The easiest way to see this in practice is that Russia’s oil and gas tax receipts have plunged, especially relative to the international price of oil, but Russian government spending has not, although it has begun to roll over slightly in U.S. dollar terms.

That relates to the other problem with a strategy focused on sanctioning Russian exports as opposed to Russian imports: Russians consistently export much more than they import during normal times, which means that the decline in export earnings that would be necessary to constrain imports is extraordinarily high. Moreover, energy exports are a minority of total Russian exports. Before the invasion, the Russian economy generated enough non-energy export earnings to cover almost the entire import bill. The government stopped publishing the breakdown with the start of the war, but it would be surprising if this relationship has changed much.

To be clear, buying less oil and gas (and coal) should always be encouraged, and if people are going to consume less polluting energy, they might as well focus on cutting their spending on hydrocarbons from murderous regimes.2 Limiting the revenues that the Russian government can earn from selling oil and gas to the democracies is a reasonable goal, but it is not going to do much for the defense of Ukraine as long as manufacturers keep sending the Russian military industry the equipment and components that it needs.

My next note will update my analysis of the financial outflows from Russia since the war began.

The EU, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China, Hong Kong, the U.K., Switzerland, the U.S., Turkey, Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia

Russia is sadly one of many to choose from.