The "Sell America Trade", QT, and Foreign Banks

"Foreign-related institutions" have shed ~$400 billion in dollar deposits at the Fed since July while reducing their overall U.S. exposure. That has balance of payments implications.

The current U.S. administration has taken unprecedented steps to alienate allies and partners even as it reduces the appeal of living and investing in the U.S.

While markets briefly seemed to be pricing in some of these changes in early April, by many accounts, the moment of the “sell America trade” seems to have passed. The prices of stocks, bonds, and currencies—although not precious metals—have all reflected strong demand for U.S. assets since April.

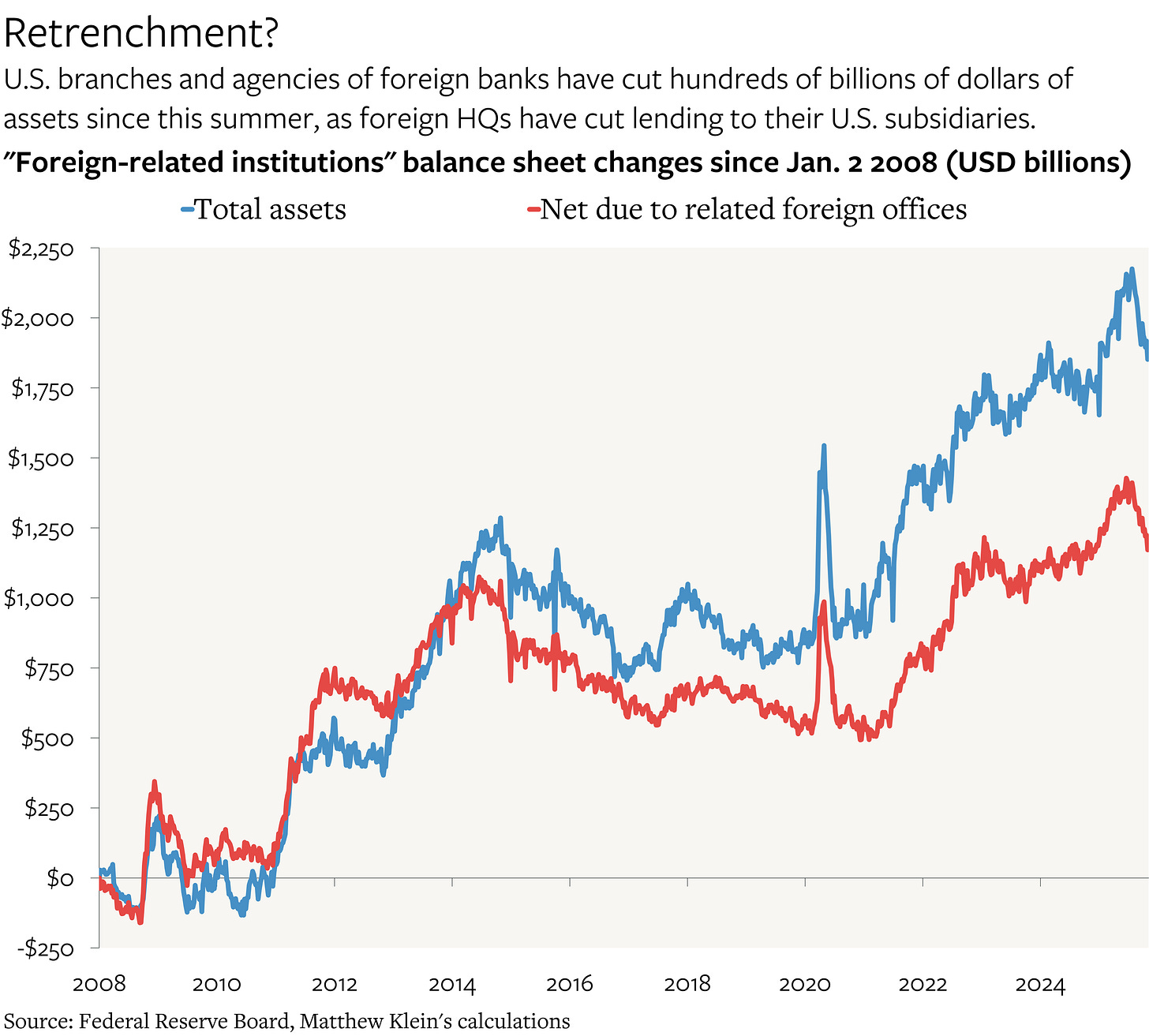

But it would be wrong to conclude from this that foreigners have ignored the regime shift in the U.S. Since July, foreign banks have been shedding assets held in their U.S. branches and agencies at one of the fastest rates on record.1 This has coincided with a sharp pullback in funding of these branches and agencies from “related foreign offices”.

The shift has gone largely unnoticed for two reasons.

First, it is still relatively small compared to the growth in foreign banks’ U.S. exposure since early 2020, even if the rate of change is substantial. As of November 5—the latest available data—net debt owed by the U.S. offices of foreign banks to their HQs or other foreign subsidiaries had only dropped back to the levels of late 2024/early 2025.

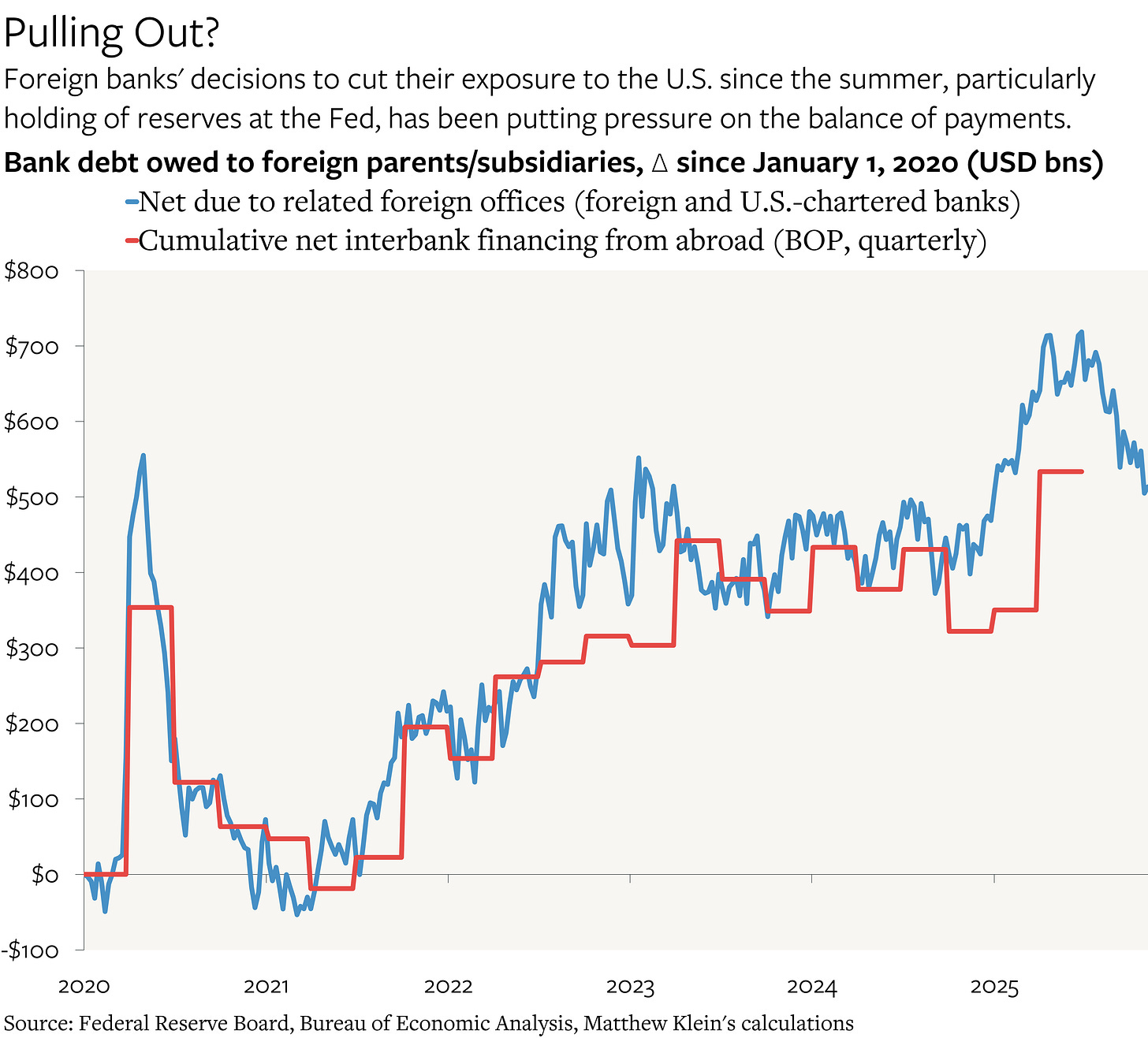

Second, the cutbacks have coincided with the ~$500 billion decline in deposits held by all banks at the Federal Reserve since the Treasury began rebuilding its own cash holdings after the debt ceiling was raised in July. The recent federal government shutdown also restricted spending relative to tax receipts, causing the Treasury General Account (TGA) to rise even further at the expense of base money available for the private sector.

But while this explains why the total volume of bank reserves has dropped, it does not explain why the U.S. branches and agencies of foreign banks have been responsible for almost all of the decline in reserves over this period, nor why they have reduced their borrowing from abroad. It is notable that, in the aggregate, the U.S. offices of foreign banks did not shed reserves in 2022, even though many U.S.-chartered banks were doing so.

This matters because foreign banks’ interoffice lending has been a meaningful source of financing for the U.S. current account deficit, especially in 2021-2022 and in 2025H1. As I have been pointing out since 2021, foreigners had helped offset the impact of dollar creation by (in the aggregate) lending export earnings back to their U.S. branches to buy reserves at the Fed, pushing up the exchange rate relative to what it would otherwise have been. That was particularly helpful when reserves yielded no interest.

If the bank flows continue to reverse, it could put downward pressure on the dollar in the absence of countervailing flows by portfolio and/or direct investors.