There Is No "Stealth Fiscal Stimulus"

The federal budget deficit is widening thanks to falling capital gains tax receipts and soaring net interest interest payments (including via the Federal Reserve). None of this is likely to boost PCE.

The U.S. federal budget deficit has widened by about 3-4 percentage points of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) since the start of 2022. The growth impulse from higher spending relative to taxation by America’s state and local governments over the same period is worth another percentage point of GDP. That is a substantial change in a short period of time, comparable to 1974, 2002, and 2008. Yet unlike those earlier periods, the current widening of the consolidated fiscal deficit is not coinciding with a spike in the jobless rate.

Some observers are calling this a “stealth stimulus” that they believe helps explain the U.S. economy’s apparent indifference to interest rate increases. Yet a closer examination of the components of government budgets that pull money out and push money into the rest of the economy suggests something else is at work.

The downturn in revenues is mostly attributable to the plunge in capital gains tax receipts after the windfall of 2021/2022, as well as the collapse in dividends paid by the Federal Reserve to the Treasury. Meanwhile, the increase in outlays is almost entirely attributable to the surge in interest payments on Treasury debt. Lower taxes and higher spending are boosting private sector disposable income, but this attribution suggests that the beneficiaries will not use much if any of the extra cash to pay for goods, services, or real assets. The “stimulative” impact is therefore likely to be much smaller than what might be expected based on the headline numbers.

The Deficit Surge In Context

From one point of view, the federal budget is behaving exactly as one would have expected based on pre-pandemic trends. Spending is rising and receipts are falling, but neither looks odd relative to what was happening in 2018-2019.

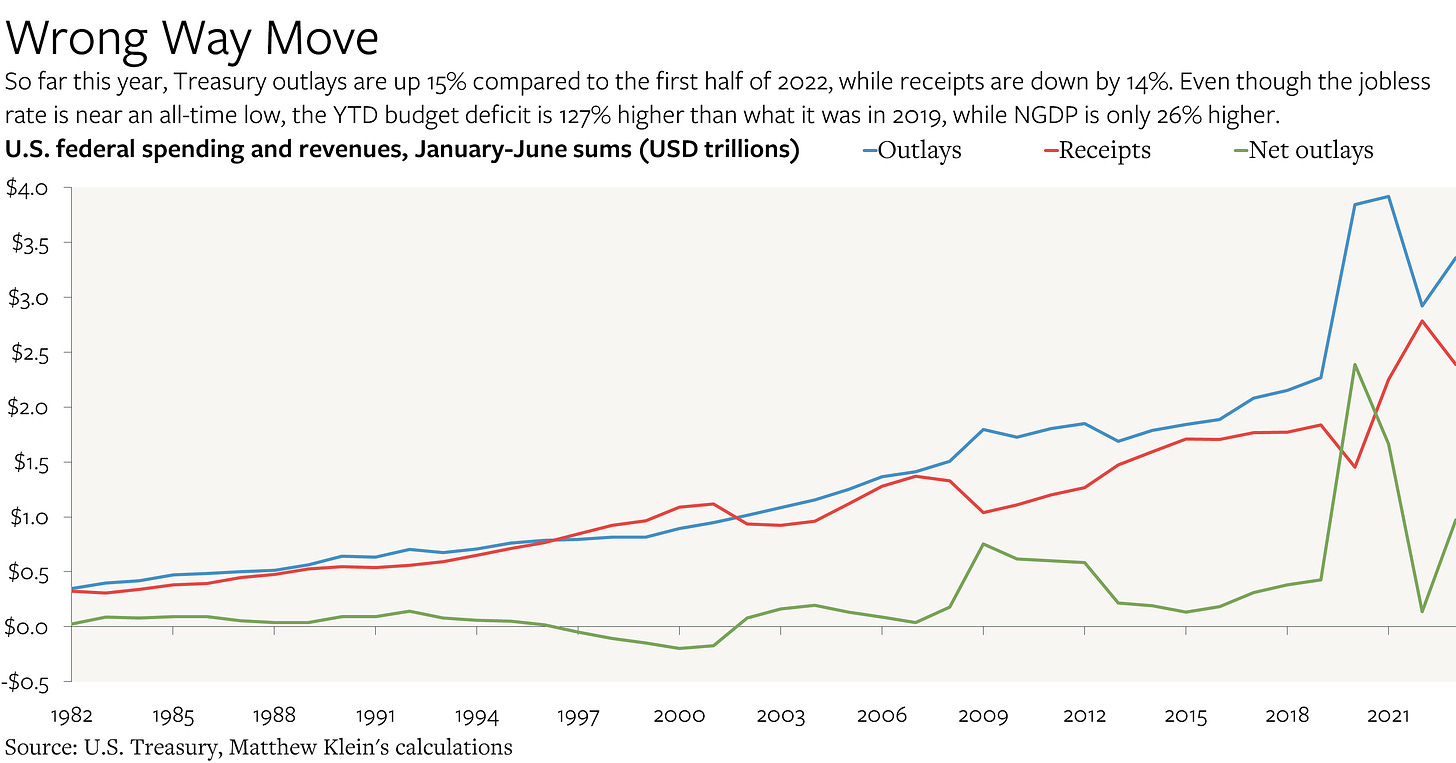

But other perspectives appear more alarming. Comparing January-June 2022 with January-June 2023 shows outlays up by 15% while receipts are down by 14%. Compared to January-June 2019, outlays are up by 48% (10% a year, on average) while receipts are up by only 30% (7% a year, on average).1 The result is that the January-June deficit has gone from $428 billion in 2019 to $137 billion in 2022 to $971 billion by 2023. Put another way, the year-to-date budget deficit is about 2.3x what it was in 2019, while nominal GDP in 2023H1 was only 26% higher than in 2019H1.

Focusing only on the April-June numbers does not make the picture look any better. While outlays grew by just 6% from 2022Q2 to 2023Q2, receipts fell by 20%. The change in the (nominal) deficit from 2022Q2 to 2023Q3 is the largest one-year increase outside of the pandemic. Federal receipts in 2023Q2 grew 5.5% a year on average since 2019Q2, while outlays grew by 9.4% a year on average.

This is extremely unusual. But as has often been the case over the past few years, the headline numbers are less informative than the details underneath.