Thinking About the Financial Implications of the U.S. Fiscal Position

The federal deficit is larger than in 2018-19 mostly because interest rates on existing debt are higher. What does it all mean?

The U.S. federal government is currently generating about $2 trillion/year of net income and financial assets for everyone else. This flow of new borrowing, currently worth about 7% of gross domestic product, is extremely unusual for a period of peacetime and high employment.

Why is this happening? Who is on the other side of these transactions? What are the consequences for the economy and financial system? How sustainable is it?

The rest of this note attempts to answer these questions in greater detail.

Comparing 2024 with 2019: Net Borrowing

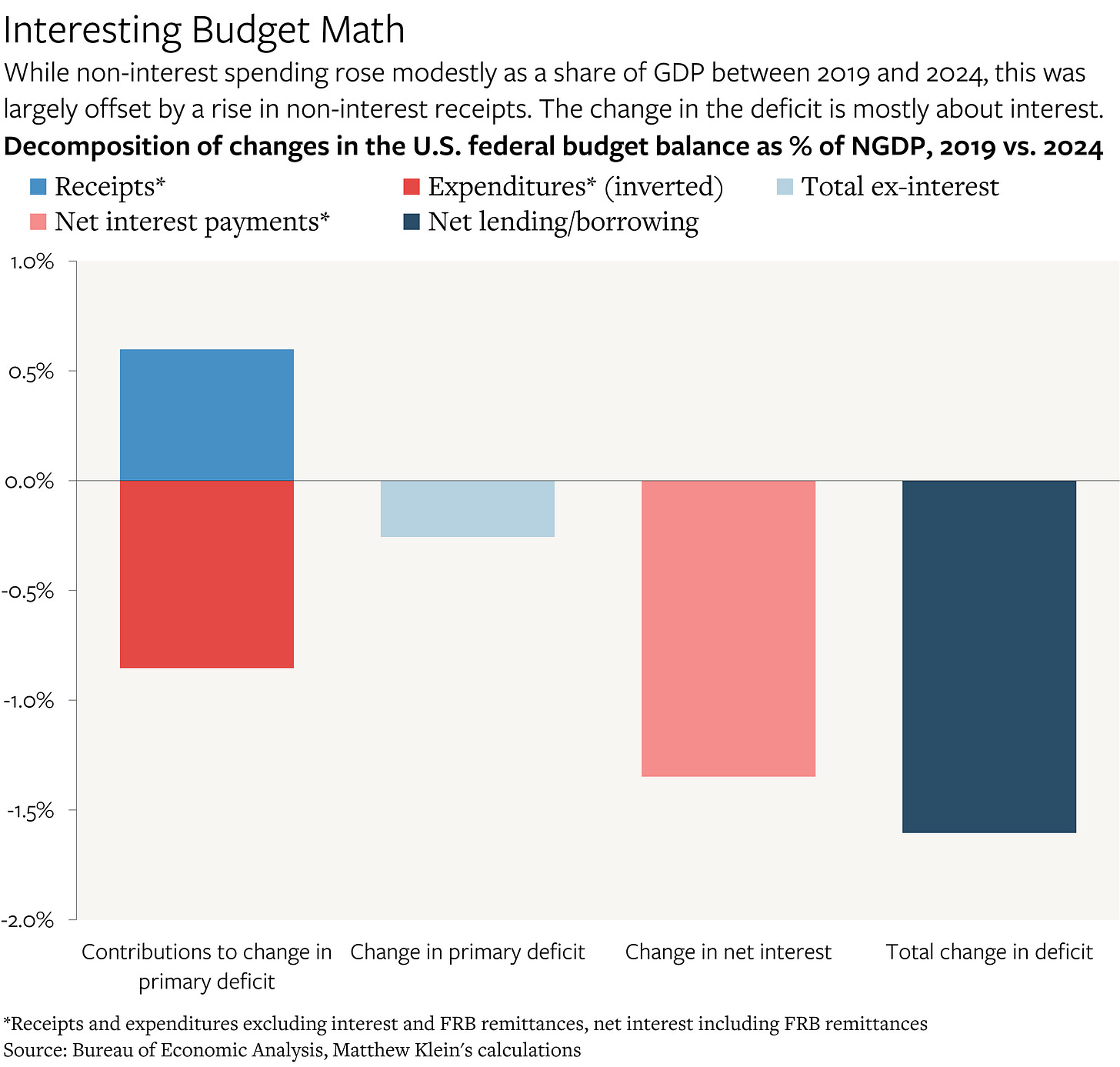

The federal budget deficit is larger now than in the years immediately preceding the pandemic. Net borrowing was worth about 5.4% of GDP in 2019, on average, compared to 7.0% in 2024Q1-Q3. The change is attributable to an increase in total federal spending from 22.6% of GDP in 2019 to 24.6% of GDP so far this year. (Receipts also rose as a share of GDP, from 17.3% in 2019 to 17.6% in 2024Q1-Q3, but by far less than outlays.) The rise in the deficit is not huge, but it is notable given the broad similarity in economic conditions.

Intriguingly, the increase in interest payments—net of interest income and remittances from the Federal Reserve—explains about 1.4 percentage points of the total 1.6pp increase in the deficit.

Higher revenues from taxes on estates, capital gains, and on noncorporate and corporate business income (an extra 1.2pp of GDP vs. 2019) more than fully offset higher federal spending on Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid1, and veterans’ benefits (0.6pp of GDP vs. 2019). Other revenues fell slightly as a share of GDP—as did compensation of federal government employees—while other spending rose slightly relative to national income. The total change in the budget balance excluding interest was only worth 0.26% of GDP, which is basically zero.

The change in the net interest balance has three parts. First, the stock of marketable debt is higher now than in 2019, increasing from about 75% of GDP to roughly 94%. Even if the average effective interest rate on debt had stayed constant, interest expense would still have increased by about 0.7pp of GDP simply because there are more obligations to service.

Second, interest rates are higher. The average yield on marketable securities rose from ~2.5% in 2019 to ~3.3% in 2024. The effective interest rate on the total stock has increased by less—because much of the debt in 2019 was issued before then, when rates were higher, while much of the debt currently outstanding was also issued before rates on new issues rose—but is still almost 0.5 percentage points higher in 2024 than in 2019. That pushed up interest payments by another 0.4pp of GDP.

And lastly, the Fed stopped generating profits for the Treasury. Before the financial crisis, the Fed held a modest portfolio of Treasury bills and short-dated notes, financed mostly by printing zero-yielding physical currency, generating seigniorage income worth about 1-1.5% of total federal receipts in 1992-2007, or 0.2% of GDP.

After the financial crisis, the Fed bought trillions of dollars of longer-dated notes, Treasury bonds, and mortgage bonds effectively guaranteed by the Treasury, while issuing interest-bearing liabilities that happened to yield nothing (mostly interest on reserves and the reverse repo facility). That pushed up remittances to 3% of federal receipts, until the Fed began to tighten by raising the rate it paid on those liabilities. By 2018/19, remittances had already fallen back to the pre-financial crisis norm relative to GDP and relative to total receipts, although remittances were starting to rise again before the pandemic.

Starting in 2022, however, policymakers lifted the central bank’s financing costs far above the yields on its asset portfolio. As of 2024Q3, the Fed has already booked cumulative losses worth just over $200 billion, and this number is likely to grow.2 The Treasury is not obliged to cover these losses when they occur, nor does it need to recapitalize the central bank, but it does have to wait until the Fed retains enough cumulative profits to cover its past losses before it can get any more remittances. From the accounting manual:

If a Reserve Bank’s earnings are not sufficient to provide for the costs of operations, payment of dividends, and maintaining surplus at an amount equal to the Bank’s allocated portion of the aggregate surplus limitation, remittances to the Treasury would be suspended. A deferred asset is recorded in this account, and this debit balance represents the amount of net earnings the Reserve Bank will need to realize before remittances to the Treasury resume.

Missing out on Fed remittances has increased the budget deficit by another ~0.3pp of GDP relative to 2019.

Deficit Financing and the Financial System

The Treasury has three basic ways of covering its deficit: running down its deposits held at the Fed (the Treasury General Account), selling bills, and selling notes and bonds.