Türkiye's Incredible Balancing Act

The country of nearly 90 million has managed to keep growing rapidly despite an increasingly fragile financial structure. Can it continue?

The Turkish economy has grown about 25% in real terms since the end of 2019, while inflation-adjusted consumer spending is ostensibly up by 60%. That is a remarkable performance for a country of 90 million people who already have living standards comparable to Hungary or Slovakia.

Even more remarkably, this growth boom has coincided with soaring inflation, a collapsing currency, and increasingly desperate policy innovations to sustain financial inflows from abroad. This should not be sustainable, yet, so far, an acute crisis has been avoided. While the situation remains extremely precarious, the Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye’s (CBRT) reversion to policy orthodoxy since last summer seems to be helping. The question is whether the central bank can continue to pull off this balancing act.

One Country, Many Currencies

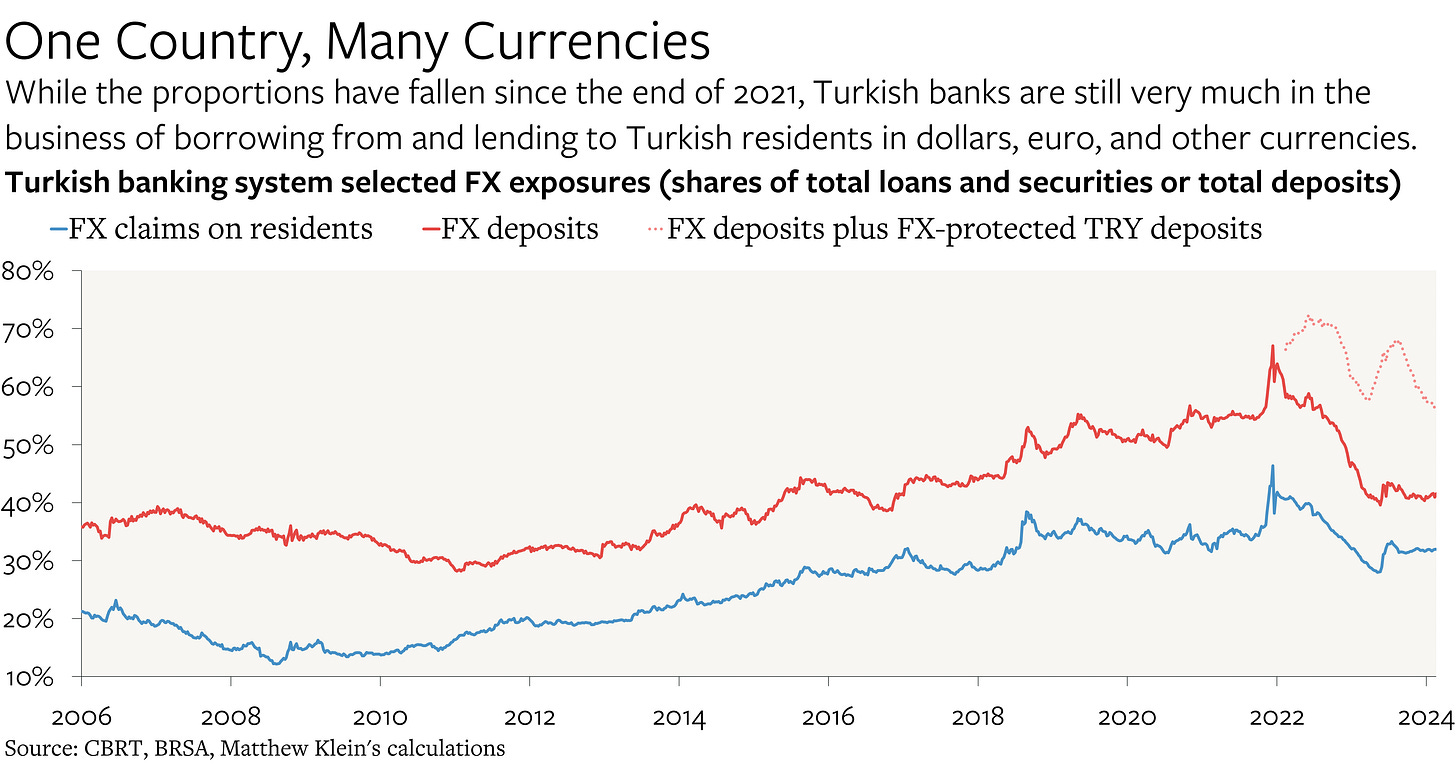

Türkiye is a $1 trillion economy tied into Europe’s advanced manufacturing networks. But it is also a country with a history of price instability and coups—and plenty of challenging neighbors. Thus, despite having its own currency and a diversified, technologically sophisticated production base, many Turks prefer to hold foreign currency (or gold) rather than Turkish lira. On top of which, a good chunk of the lira they hold in the banks has been in the form of lira-denominated “FX-protected deposits” (KKM and DDM).1

About 40% of Turkish bank deposits are denominated in U.S. dollars, euros, gold, or other foreign currencies, with another 15% of deposits in lira-denominated KKM and DDM (down from a peak of 25% last summer). As of now, a little less than half of FX deposits are in USD, a third are in euro, 16% are in gold or other “precious stones” accounts, and the remainder are in other currencies.

Turkish banks accomodate this by lending in foreign currency to Turkish businesses and, to a lesser extent, by holding FX-denominated Turkish government debt. FX-denominated (or FX-linked) claims by Turkish banks on Turkish residents are worth about a third of total bank loans and securities.

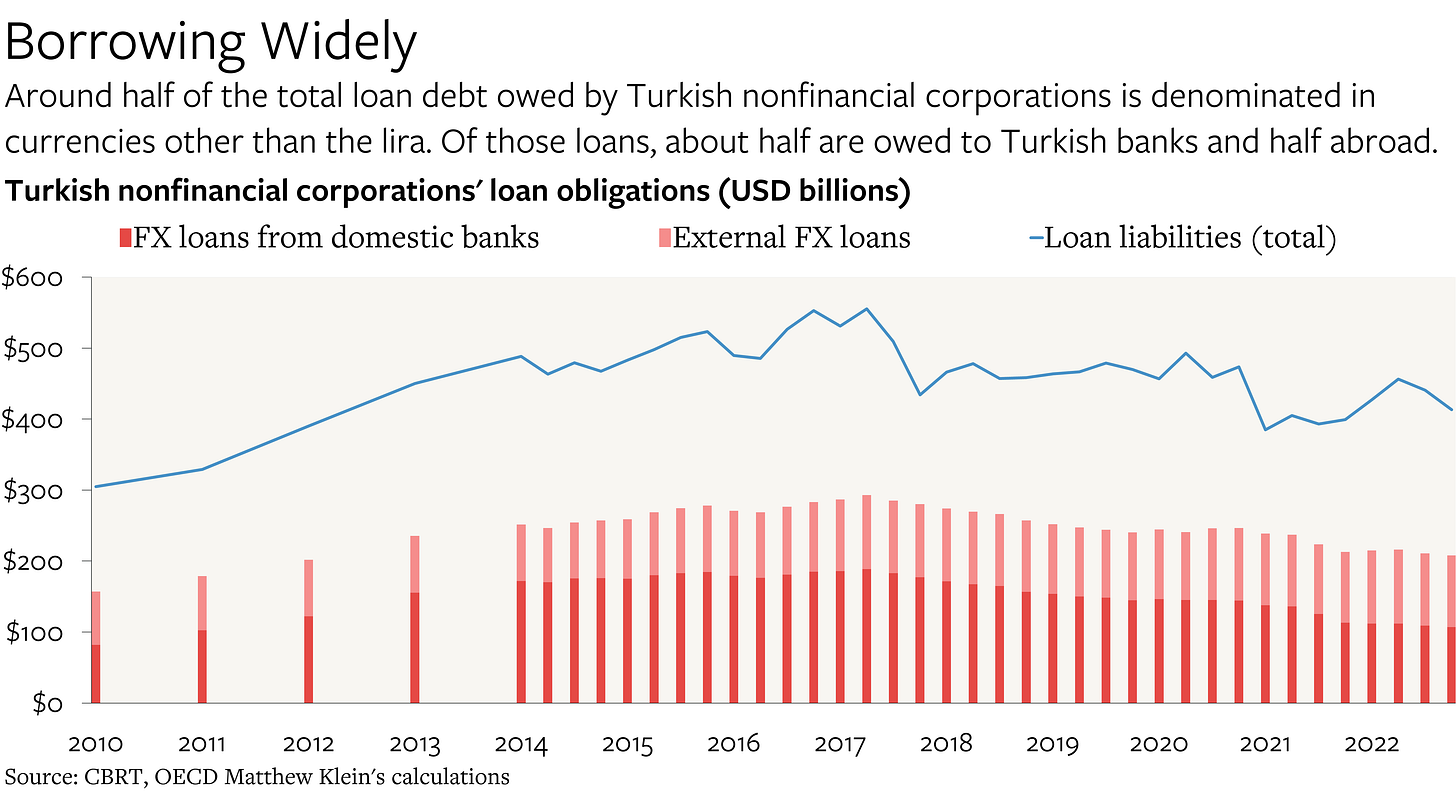

On the other side, Turkish nonfinancial corporations hold about two-thirds of their ~$170 billion in cash and equivalents in FX-denominated accounts (mostly in Turkish banks). Half of their total loan borrowing is denominated in FX, with that split about equally between FX loans from Turkish banks and external loans.

Thanks to aggressive deleveraging over the past six years, Turkish nonfinancial corporates now hold (in the aggregate) about as much FX deposits in the Turkish banking system as they borrow in FX-denominated loans from Turkish banks. They are still substantial net FX debtors, however, due to their modest holdings of FX in banks outside Turkey and their large but stable external debt position.

The CBRT Becomes Profligate on Everyone Else’s Behalf

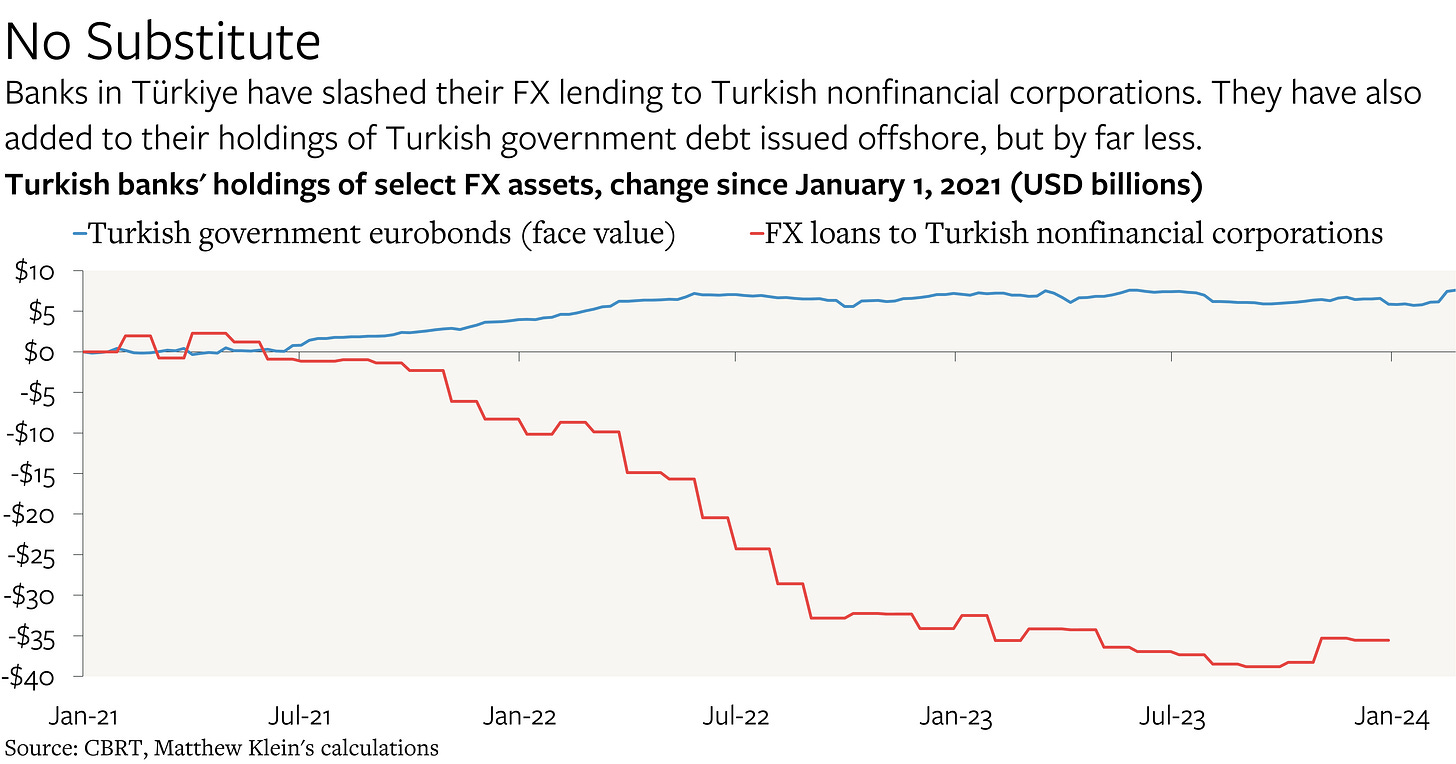

If Turkish banks have been lending less to Turkish nonfinancial corporations in foreign currency without cutting their FX deposit liabilities commensurately, someone else must be picking up the slack.

But Turkish households are not borrowing in FX—and not borrowing much in lira, either. And while Turkish residents as a whole have been buying up some Turkish government debt that was originally issued abroad, the impact has been partly offset by reductions in foreigners’ holdings. Moreover, Turkish banks’ purchases of Turkish government eurobonds since the start of 2021 (about $8 billion in additional face value) have been far smaller than the drop in their holdings of FX loans to Turkish nonfinancial corporations over the same period ($36 billion).

Instead, the CBRT itself has been borrowing hard currency from both the local banking system and the rest of the world to help prop up the lira and to finance Türkiye’s peristent current account deficit.