U.S. Job Market Still (Surprisingly?) Good. Inflation Risk Is Paramount.

Core measures of labor demand remain strong, while wage growth is holding steady (or re-accelerating). But there are a few pockets of weakness that bear watching. Plus: China's investment slowdown.

It is tempting, after several years when the U.S. economy was the envy of the world, to conclude that the cycle has turned thanks to the malignant policymaking of the people currently in power. And while there will likely be severe and lasting harms to the U.S. economy—and to the world more generally—from many of this administration’s policies1, the data do not yet imply that the business cycle has rolled over.

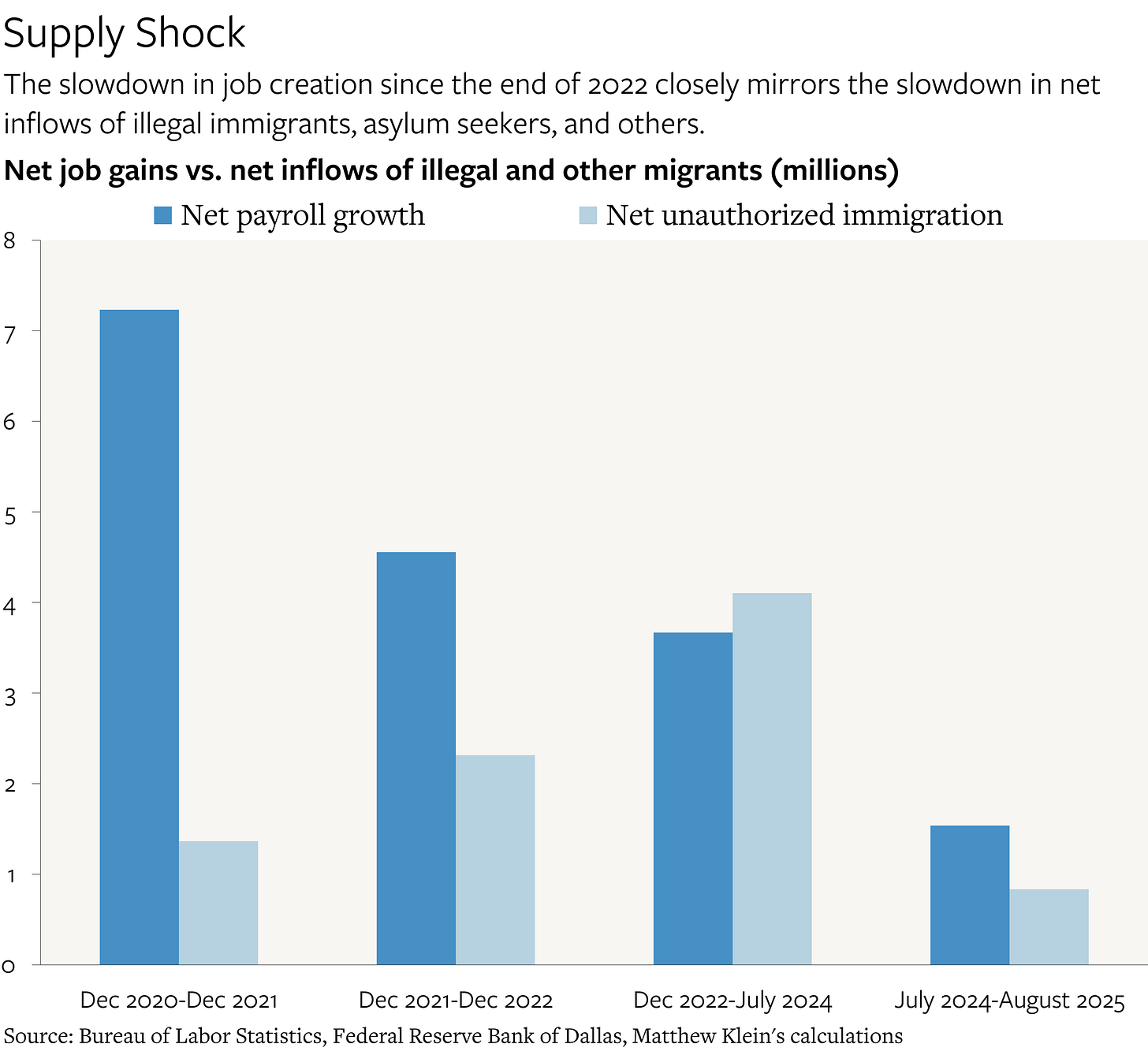

Instead, the latest numbers on jobs and incomes are consistent with the view I have had for some time: real growth has been relatively stable after accounting for changes in net immigration, while nominal growth remains persistently faster than would be consistent with 2% inflation. This suggests that it would be unwise for the Federal Reserve to unleash the latent financial firepower of consumers and businesses by lowering borrowing costs much further from current levels, if at all.

Broad-Based Gains, Concentrated Pain

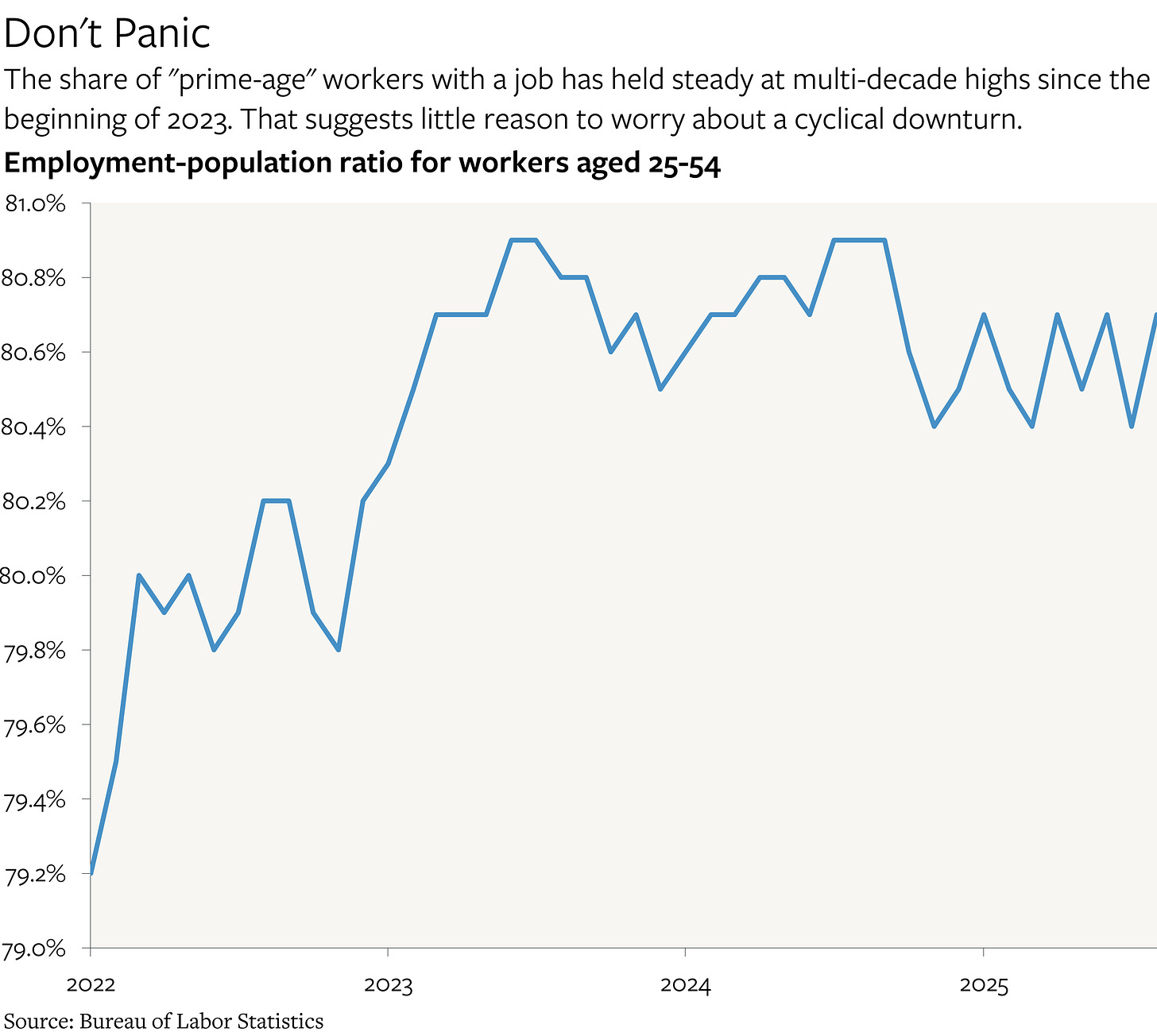

The single best indicator of job market health is the share of workers aged 25-54 who say that they have a job. This measure is insensitive to longer-term trends in education and retirement preferences, and it is also immune to confusions caused by changes in whether people are officially classified as “unemployed” or “not in the labor force, want a job now”. This measure was quicker to catch both the downturn of the early 2000s and the financial crisis. It also did a better job of capturing the persistent job market weakness following both of those episodes than the headline unemployment rate (also known as U-3).

It is therefore encouraging that the “prime age employment rate” remains essentially unchanged over the past 2.5 years at a multi-decade high. The current reading of 80.7% is only just below the recent peak of 80.9%. For perspective, this indicator had dropped by 1.6 percentage points between January 2000 and August 2001.

This reflects healthy demand for labor, because the total number of hours worked has been rising in 2025 (0.65% annualized) at about the same rate as in 2019 (0.75% annualized), even though the growth rate in the number of payroll jobs has been about half as fast due to the sharp swing in net immigration.

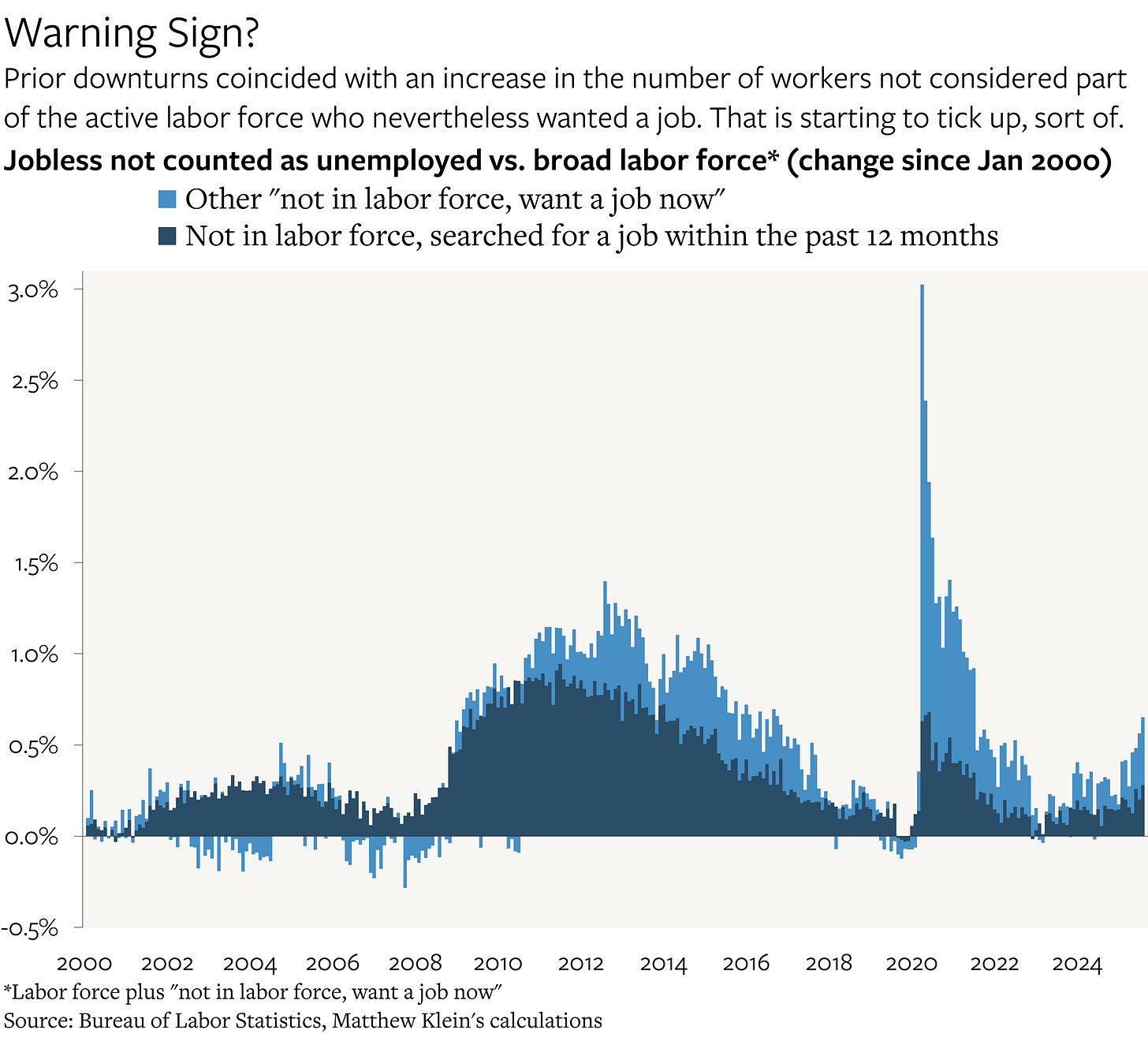

The stability of the prime age employment rate and the robust growth in hours worked stands in contrast to the overall unemployment rate, which seems to be breaking out of the range it had been sitting in since last summer. Alarmingly, this has coincided with a rise in the share of Americans who are not counted as unemployed, because they have not searched rigorously for a job within the past four weeks, but nevertheless say that they “want a job now”. The good news is that the subset of these workers who say that they have searched for a job within the last 12 months has been rising much less, as is the (even smaller) subset who have not looked recently because they are “discouraged”.

By definition, if prime age employment has been stable at the same time that U-3 has been rising and at the same time that workers have been dropping out of the labor force, job market weakness must be concentrated elsewhere. Specifically, Americans under 25. While jobless rates for the 16-24 age cohort have historically been both higher and more volatile than for workers with more experience, that does not explain the relentless surge since the beginning of 2024.2 And even though there are far fewer American workers in that age bracket than in the 25-54 or 55+ categories, the magnitude of the unemployment rate increase has been big enough to affect the aggregate numbers, particularly when it comes to unemployment by people who are either new to the labor force or who are re-entering the labor force after taking time off from job search.