Why Have Rate Hikes Not Done Anything?

Houseolds and businesses have responded to higher interest rates by issuing less debt, yet the shift from borrowing to saving has not affected real output, consumer spending, or employment.

American companies and consumers have cut their borrowing in response to higher interest rates, but this has not affected their actual spending. The result is that the U.S. economy is still continuing to grow briskly in both real and nominal terms despite years of allegedly “tight monetary policy”.

The explanation seems to be twofold. First, borrowing has not been that important ever since global financial crisis, which limited the impact of any negative credit impulse. Instead, spending has been financed overwhelmingly out of income growth, which continues to be faster than before the pandemic. At the same time, healthy balance sheets—both in terms of lower indebtedness and persistently higher holdings of cash and equivalents—make it easier for businesses and households to look through any temporary income volatility and keep spending.

This has lasted far longer than many had thought possible, which suggests that the “neutral” calibration of interest rates may be substantially higher than it was before the pandemic.

Corporate Capex Cornucopia

American nonfinancial corporations mostly raise cash by borrowing money. In the aggregate, net equity issuance (including M&A) has been persistently negative since the mid-1980s, with gross issuance usually offset almost exactly by buybacks.1 Meanwhile, most of corporate America’s post-tax profits, including profits booked abroad, are paid to shareholders as dividends.

The implication is that capital spending is usually financed by debt. Changes in corporate borrowing have coincided with changes in capex since the mid-1970s. (Before that, investment cycles were far more volatile and seem to be independent of debt trends.)

Yet something different has happened over the past few years. Even as net issuance of bonds and loans by nonfinancial corporations has dropped to zero (blue line below), real nonresidential capital spending has continued to grow faster than it did before the pandemic (red).

In the aggregate, of course, business investment is self-financing, because buyers book the cost as an asset that can depreciate over time while sellers book revenues immediately. This is why rising investment and rising profits tend to go together. And profits have been booming recently, with pretax domestic nonfiancial corporate profits up by 8% in 2023.

This virtuous circle could break if recent investments are not validated via higher sales to consumers—but unless (or until) that happens, corporate America can continue to grow even if higher borrowing costs end up making debt less attractive.

Credit-Free Consumption

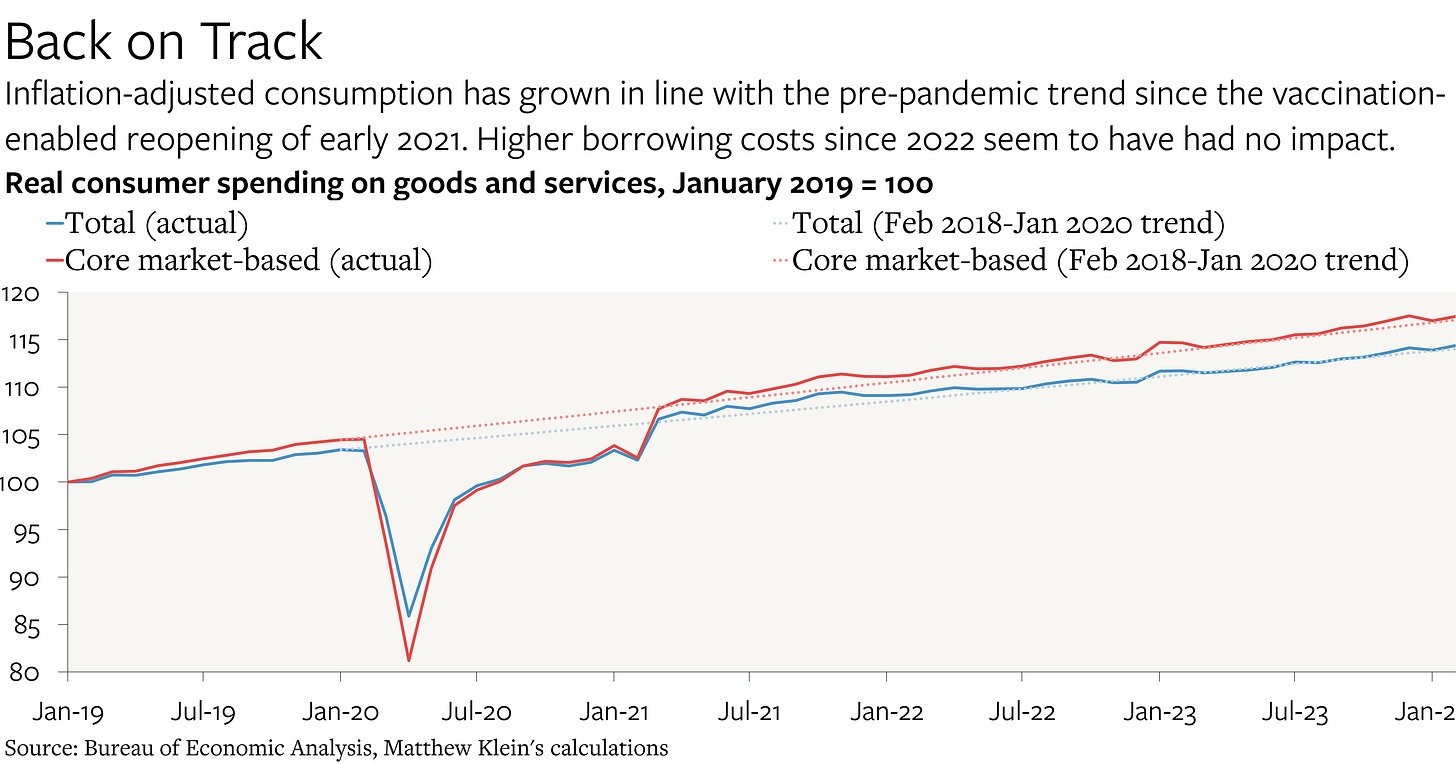

Encouragingly, consumer spending seems to be similarly divorced from the changes in financial conditions since the end of 2021. Robust nominal income growth has helped keep inflation-adjusted spending in line with pre-pandemic trends despite higher prices.

Higher consumer spending has been financed primarily by more people working (at better jobs), for longer hours, at higher pay.