Appeasing the Chinese Government "For the Climate" Makes No Sense

China's leaders have their own reasons to rapidly decarbonize and have already committed to achieving net zero greenhouse emissions.

China is the world’s largest polluter, responsible for 31% of global carbon emissions as of 2020. Moreover, about two thirds of the increase in global emissions since 2007 can be attributed to rising pollution from China. There is no effective response to climate change that excludes China.

The good news is that China’s leaders are keen on rapidly decarbonizing for their own reasons: national security and public health. Importing oil and gas from across the oceans is risky, while burning coal to generate heat and electricity makes the air unbreathable. We should all hope that they succeed in greening their energy system—but if they fail, it won’t be because of anything Western diplomats did or didn’t do. What matters are China’s internal dynamics.

Some people, however, seem to believe that the Chinese government will only cut emissions if it’s given a free hand to continue committing atrocities against the Uyghur and Tibetan minorities. Appeasing the Chinese government on these issues for the sake of the climate might sound like the type of diplomatic “grand bargain” that Metternich or Kissinger might have negotiated—but it would be a catastrophic mistake grounded in a misunderstanding of China’s own priorities.

China’s own diplomats seem happy to perpetuate this misunderstanding, with Foreign Minister Wang Yi warning that “China-U.S. cooperation on climate change…cannot sustain without an improved bilateral relationship.”

Thus, Robert Kuttner of The American Prospect claims that senior officials within the Biden administration have been pressuring members of Congress to hold off on passing legislation that would ban U.S. imports of Chinese goods made by Uyghur slave labor. Spokesmen for both the National Security Council and the State Deparment have vehemently denied the report, with the NSC calling it “absolutely false”. I hope that the denials are correct and that Kuttner is wrong, because there is no good reason to appease China “for the climate”.

China’s dependence on fossil fuels is dangerous for China

China is rapidly becoming dependent on imported energy—and the only way it can guarantee that it won’t get cut off from essential supplies in faraway countries is by totally decarbonizing.

China consumed about 145.5 exajoules of energy in 2020, according to the latest BP Statistical Review of World Energy. Of that, just over 82 exajoules came from burning coal, 28.5 from oil, 12 from natural gas, 12 from hydroelectric power, and the rest from wind, nuclear, solar, and other alternative energy sources such as geothermal and biomass. In other words, fossil fuels satisfied about 84% of China’s total energy needs. But that’s down from 94% as recently as 2007, because Chinese consumption of alternative energy has grown much faster than demand for dirty fossil fuels.

The mix of fossil fuels has also changed dramatically, with coal losing ground to oil and natural gas. Chinese coal consumption has been essentially flat since 2013, and even before that, demand was rising more slowly than for oil and gas.

The relative decline of coal is significant not just because coal is dirtier, but also because it’s the only fossil fuel that China produces domestically in sufficient quantities. More oil and gas means more imports—and therefore less energy security.

But it’s not as if the Chinese government has a choice to stick with coal. In 2020, China had about 143 billion tons of proved coal reserves and Chinese coal miners dug up about 3.9 billion tons. That means that China would completely run out of domestic coal by 2057 if there were no new discoveries and a constant rate of mining. This helps explain why the Chinese government has been so aggressive in pushing the transition to alternative energy sources.

Coal has three main uses in China: as the most important fuel for the country’s electric power plants, as an essential ingredient for making steel, and as the main fuel for northern China’s system of centralized heating.

Chinese steel output has risen sharply in the past few years. That’s boosted demand for coking coal, much of which is imported. But this probably isn’t sustainable over the long term given China’s history of steel overproduction and the government’s stated desire to cut back on wasteful construction projects. While demand for metallurgic coal may be strong now, the longer-term outlook is bleaker.

China also continues to build more coal-fired power plants fueled by local supplies, with the number of terawatt hours of electricity coming from coal up more than 20% since 2013. But that’s occurred in a context of soaring investment in alternative energy sources and extremely rapid growth in total demand for electricity. The share of electricity generation coming from coal has dropped from 75% in 2013 to 63% as of 2020.

Chinese coal consumption has been flat even as steelmaking and electric generation have grown because coal has become less important as a heat source in the winter. Burning coal in urban centers is terrible for the breathability of the air—and that’s something the Chinese government cares about. Despite being an authoritarian regime that puts the interests of ordinary people far below the perceived needs of the Communist Party, the Chinese government is sensitive to complaints about the quality of the environment, both as a matter of national pride and because it’s one of the biggest reasons why Chinese choose to emigrate.

The big replacement for coal as a heat source has been natural gas.1 While China produces about 5% of the world’s natural gas, it consumes almost 9%. More than 40% of China’s gas needs are now satisfied by imports, up from essentially zero as recently as 2008.

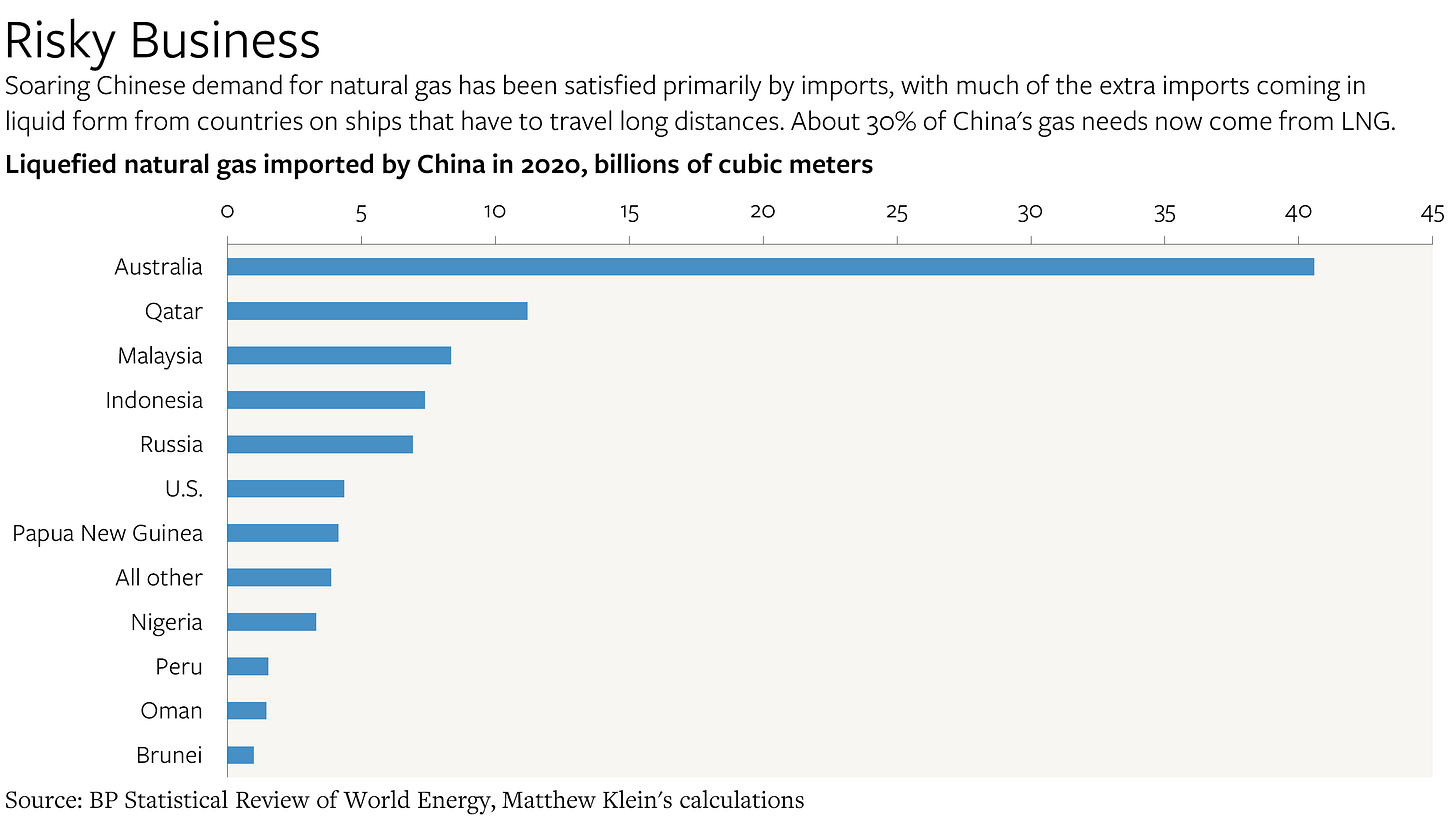

Most of China’s additional gas imports since 2015 have come from liquefied natural gas (LNG) rather than from pipelines. About 30% of China’s total gas consumption comes in by ship as LNG, with much of that gas coming from countries that might not supply Chinese customers depending on the international situation. Australia and the U.S. alone supply half of China’s LNG imports.

China is even more dependent on imports of crude oil. Despite being one of the world’s largest oil producers—behind Canada but ahead of Iraq, Brazil, the U.A.E., and Kuwait—China is now the world’s biggest net importer of crude.

As recently as the early 1990s, China was a net oil exporter, but production growth slowed and began to decline after 2015. As of 2020, Chinese oil production was 20% higher than it was in 2000, but consumption was three times what it was two decades ago. As a result, the deficit between Chinese oil production and consumption is now worth about 10.3 million barrels a day, or 73% of total oil consumption. That’s up from 31% in 2000 and 52% as recently as 2008.

The main reason is that Chinese consumers are much more likely to own cars and drive around the country than in the past. The number of passenger vehicles in China has grown from 9 million in 2000 to 61 million by 2010 to 225 million by 2019. Unsurprisingly, the government has been pushing consumers to buy electric vehicles to reduce the oil deficit, although those efforts haven’t yet made much of a dent.

As a result, China’s combined oil and gas energy deficit is worth about 25.6 exajoules—more than double what it was as recently 2011. Including coal imports, almost 20% of China’s energy now comes from abroad. That’s an uncomfortably high—and rising—level of dependence on foreign supplies.

China would be vulnerable to losing access to most of those oil and gas imports if shipping lanes were restricted, particularly at the choke point of the Strait of Malacca. From this perspective, the AUKUS agreement on regional security could be more effective at encouraging China to decarbonize than any other diplomatic initiative.

The Chinese government is aware of all this

That’s probably why Xi Jinping, China’s current paramount leader, committed the country to total decarbonization by mid-century. Here’s exactly what he said in a speech to the U.N. General Assembly on September 22, 2020 (emphasis mine):

Humankind should launch a green revolution and move faster to create a green way of development and life, preserve the environment and make Mother Earth a better place for all…The Paris Agreement on climate change charts the course for the world to transition to green and low-carbon development. It outlines the minimum steps to be taken to protect the Earth, our shared homeland, and all countries must take decisive steps to honor this Agreement. China will scale up its Intended Nationally Determined Contributions by adopting more vigorous policies and measures. We aim to have CO2 emissions peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.

These aren’t just words. The CO2 intensity of the Chinese economy has plunged in recent years as the government restrained excessive investment in physical infrastructure and real estate. In fact, the recent ructions in global coal and natural gas markets are largely attributable to the Chinese government’s overzealousness in cutting back on domestic coal production and imports, as Alex Turnbull has explained.

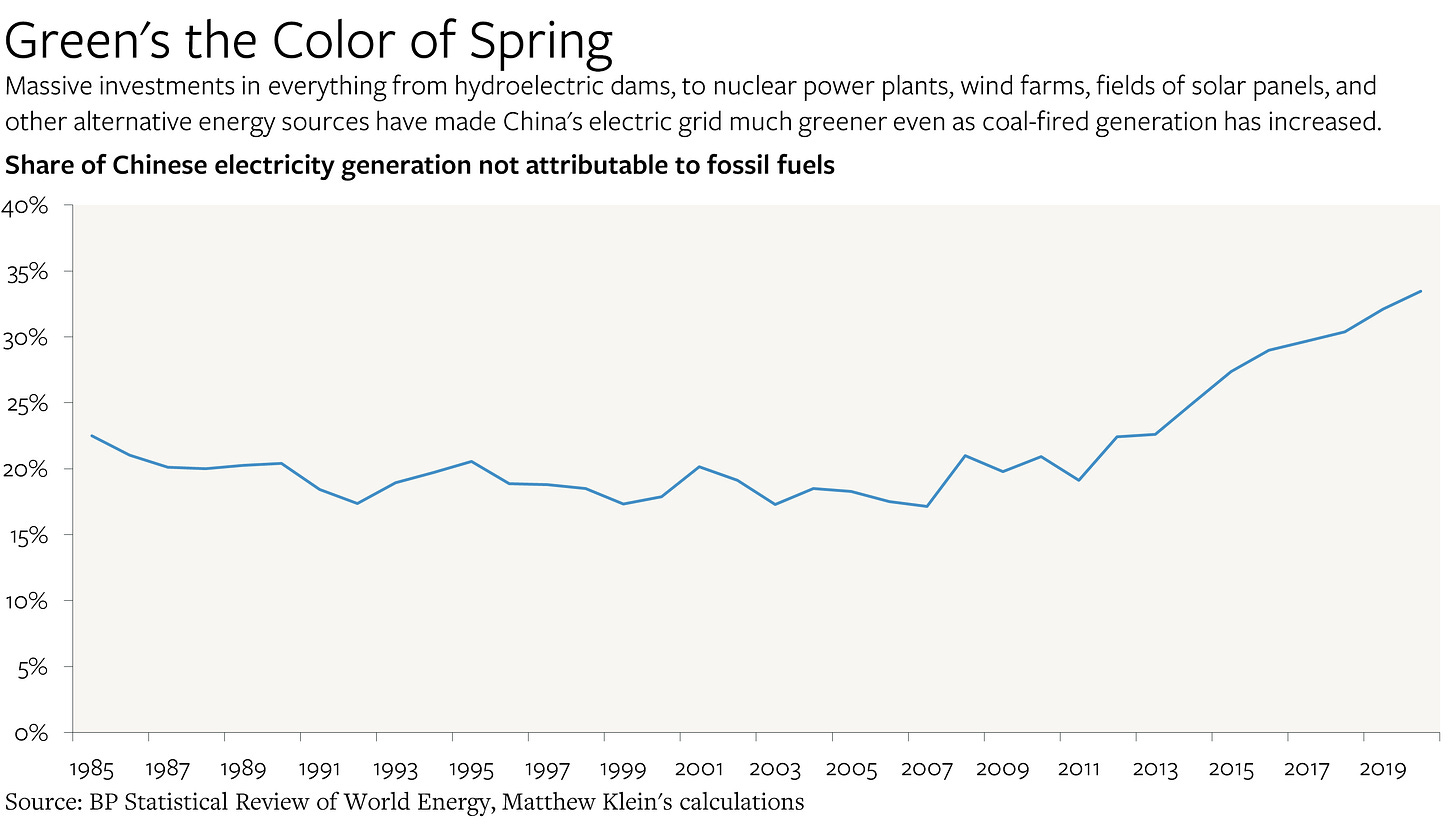

Moreover, the Chinese government has been rapidly greening the electric grid. A third of all terawatt hours of electricity generated in 2020 came from sources other than coal, oil, and gas, up from 19% as recently as 2011. From 2011 through 2020, coal-fired generation was up 33%, but hydroelectric power doubled, nuclear power quadrupled, geothermal and biomass output quintupled, wind power sextupled, and solar power increased by 95 times. If recent trends continue, China’s electric grid will be fully decarbonized before Xi’s 2060 deadline—and it’s likely that recent trends will only accelerate as natural gas and coal become increasingly unattractive.

Combine that with China’s efforts to electrify the vehicle fleet and the likely future deployment of carbon capture technology, and it suggests that the country is well on its way towards meeting its self-imposed climate objectives, which are in turn broadly consistent with the benchmarks laid out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

None of this is to say that China can’t do better—we can all do better!—but it does mean that there is nothing to be gained by caving in to PRC demands in the hope that it will encourage greener environmental policies. Even without the existential threat of climate change, China’s leaders are behaving as if decarbonization is in China’s interests.

Gas is also increasingly being used as a fuel to generate electricity, although it’s much less significant compared to both coal and renewables. Put another way, gas represents about 8% of China’s total energy consumption but only 3% of China’s electric power generation.