Are Consumers Retrenching?

"Immaculate disinflation" works best if consumer spending rises less than incomes. That may finally be happening.

There are hints of something very encouraging in the latest numbers on incomes and spending, as well as the latest detailed estimates of wealth, saving, and borrowing. Consumers might be cutting back on spending even as wages continue to rise at a solid clip, with the difference showing up in the form of improved household balance sheets. Should it continue, this combination would help trend inflation to slow without any hit to the job market.

For nearly two years, I have been skeptical that inflation would sustainably return to the Federal Reserve’s 2% yearly goal without some deceleration in the pace of wage growth.

My reasoning was simple: since inflation is the difference between spending on goods and services (in dollars) and the real production of those goods and services (in…whatever units you prefer)1, since most spending on goods and services is financed out of wage income, and since most wage income is spent immediately on goods and services, inflation is, over time, mostly determined by the pace of pay increases. Wages rising steadily at 5% a year, for example, would only be consistent with 2% yearly inflation over time if the real volume of goods and services that people wanted to buy rose at a trend rate of ~3% a year—which has barely ever happened before.

But the math could change if workers collectively decided to spend a smaller share of their paycheck on goods, services, and housing. Instead of extra income feeding directly into higher demand, which would put upward pressure on prices to the extent that production is constrained, some of the higher pay would translate into healthier household balance sheets.2 While it is unlikely that spending could rise slower than wages for very long—sooner or later, consumers would realize that they were leaving money on the table—it could lead to a period of relatively benign disinflation, which in turn might make it easier to accept slower nominal wage growth afterwards.

This is all very tentative, and subsequent data revisions might change some of the points I am currently making, but it is something to watch.

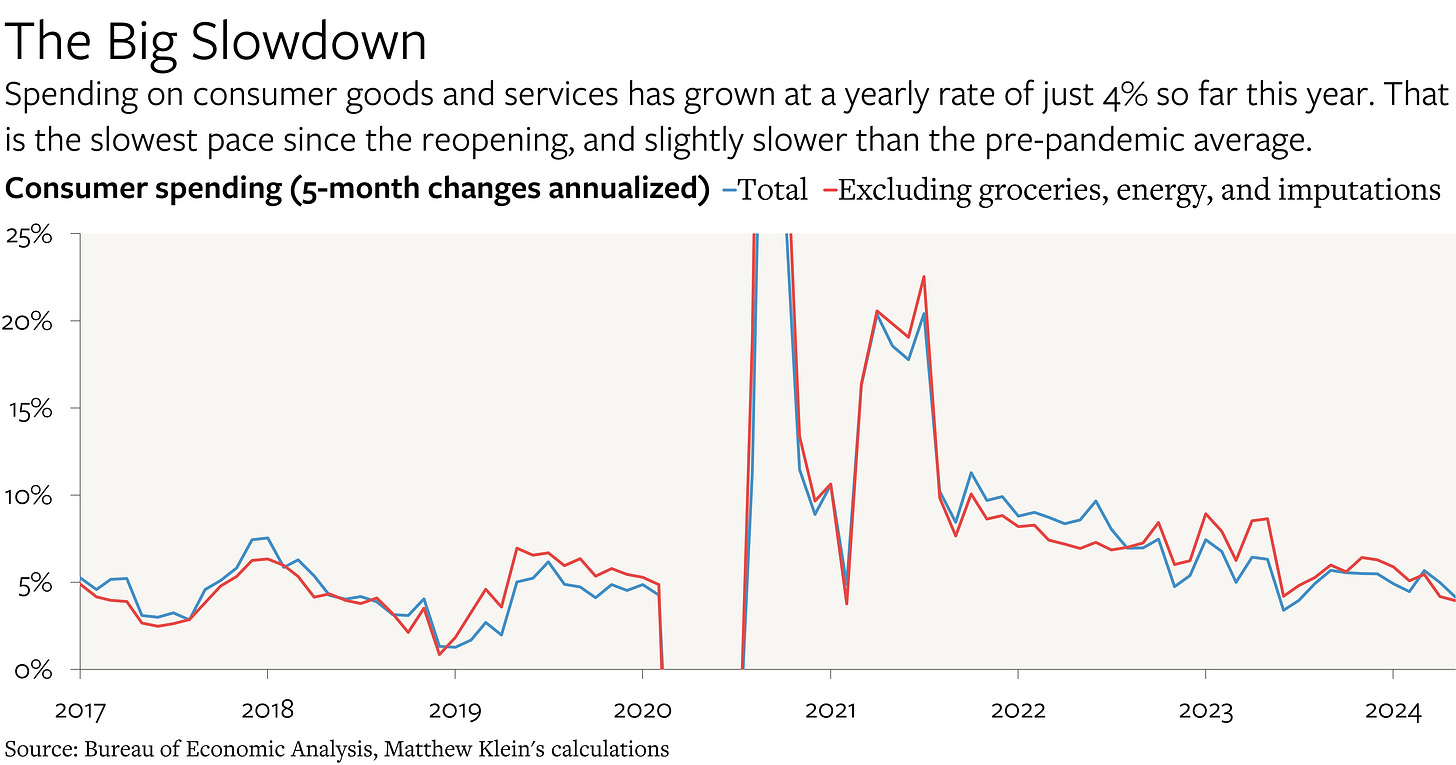

The Consumption/Income Disconnect

Since the end of 2023, the total amount of dollars earned as labor income net of social insurance taxes has grown at a yearly rate of 6%. Over the same period, nominal consumer spending has grown at a yearly rate of just 4%. (Capital income has grown by 3% annualized.) Focus specifically on the subset of consumer spending that excludes imputations as well as volatile food and energy prices, and nominal spending growth year-to-date has been slower than in any five-month period since the great reopening. In fact, the annualized growth rate in the dollar value of core “market-based” consumer spending so far this year is about half a percentage point slower than the January 2018-February 2020 yearly average of 4.4%.

By contrast, net labor income is currently rising about 1 percentage faster than the pre-pandemic pace.

While the relationship between labor income and consumer spending is never exact, especially over shorter time periods, this divergence is still striking. In the first few months of this year, the nominal spending slowdown seems to have translated into relatively weak real growth as inflation temporarily accelerated. But more recent news on inflation has been better, especially when it comes to Fed officials’ preferred measure of underlying price pressures. If that holds, it should improve the real growth numbers.

The disconnect between consumption and incomes is also showing up in households’ balance sheets.