The Unresolved Tension Between Prices and Incomes

U.S. inflation numbers continue to come in nicely, but the data on wages still suggest that the recent disinflation should eventually reverse even without new supply shocks.

Back when U.S. consumer prices were rising at double-digit yearly rates, I was among those who insisted that the aggregate numbers were being inflated by temporary disruptions to the mix of goods of services people wanted1, as well as by temporary disruptions to our collective ability to produce and distribute any goods and services.

Eventually, I argued, those distortions would fade as society normalized, consumer preferences stabilized, and businesses had a chance to adapt. As that happened, some prices that had jumped up during the period of adjustment might fall outright, or rise unusually slowly, either of which might temporarily depress official inflation readings relative to underlying price trends. But sooner or later, those underlying forces—whatever they were—would assert themselves and dictate the path of inflation going forward.

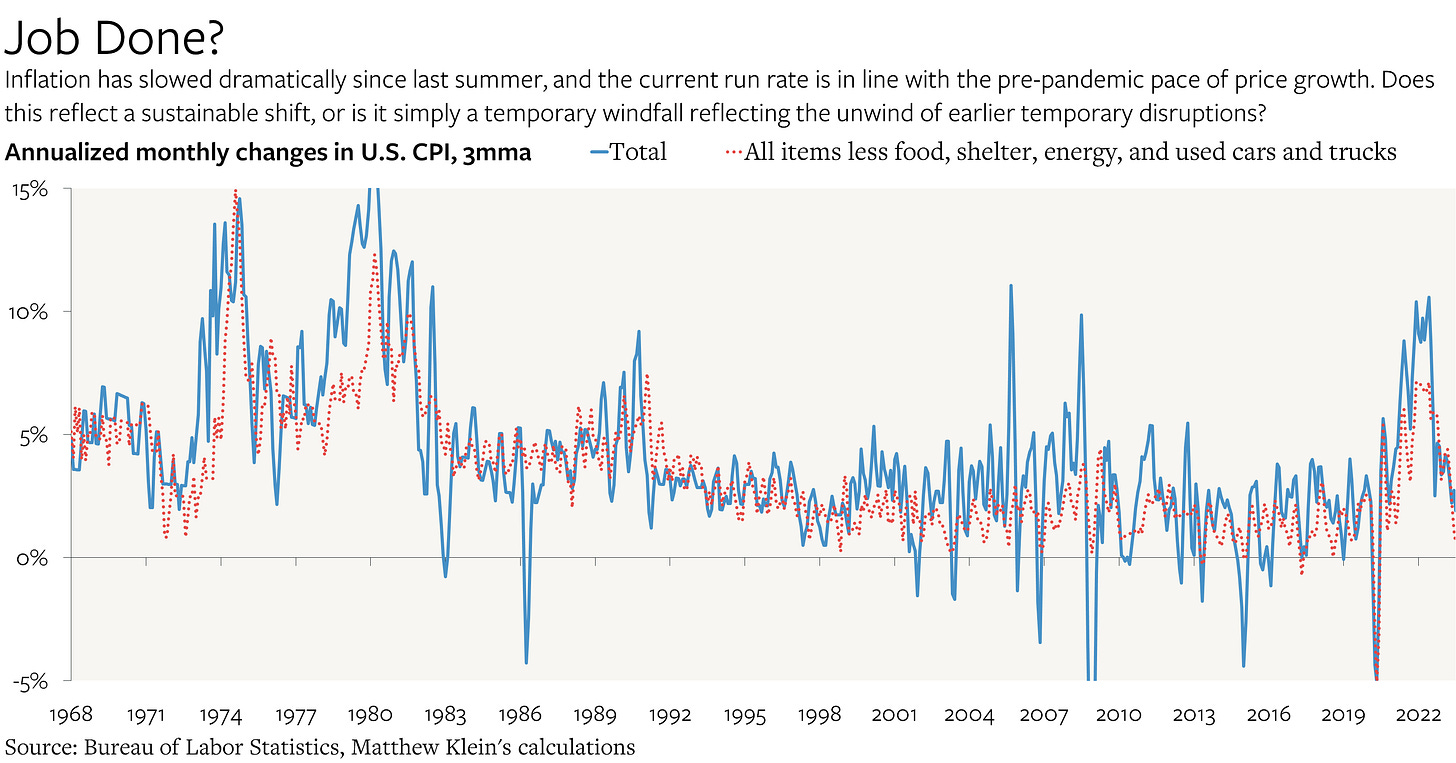

When inflation was raging in 2022H1 and some observers were calling for 8% interest rates, this perspective made me seem relatively sanguine (or naive, depending on your point of view). Things have changed. The latest Consumer Price Index (CPI) data show that, as of July, prices were rising at a yearly rate of just 1.9% on average over the prior three months, 2.6% over the past six months, and 3.0% since last summer.

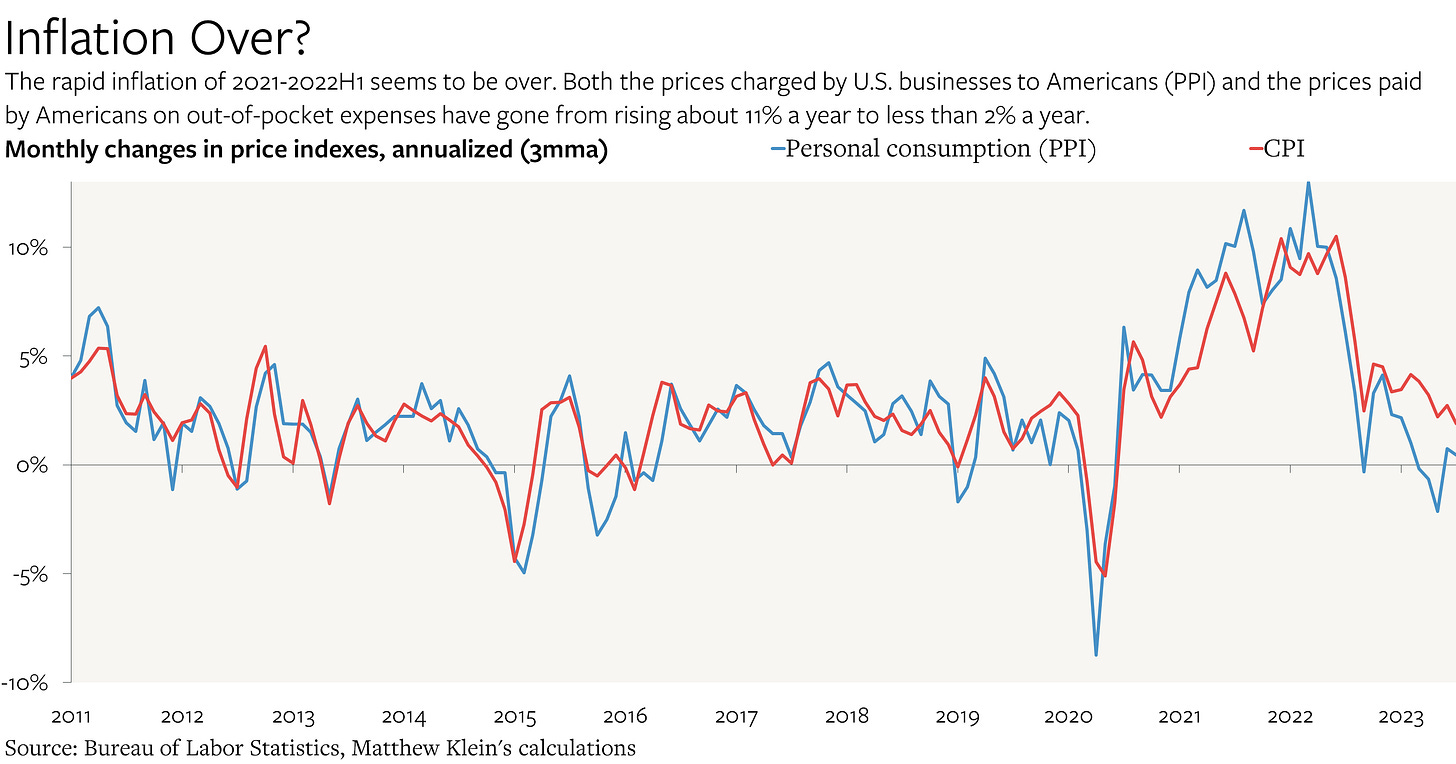

The prices charged by American businesses as reported in the Producer Price Index (PPI) are rising by even less2, with the “final demand” index down slightly since the peak in January and the “personal consumption” subindex up just 0.5% at a yearly rate on average over the past three months.

Much of this most recent improvement can be attributed to the falling prices of manufactured goods, which is exactly what those of us who had highlighted the temporary nature of the disruption were expecting.

Even prices at sitdown restaurants—which I continue to believe are the best single bellwether of underlying inflationary pressures—seem to be moving in the right direction.

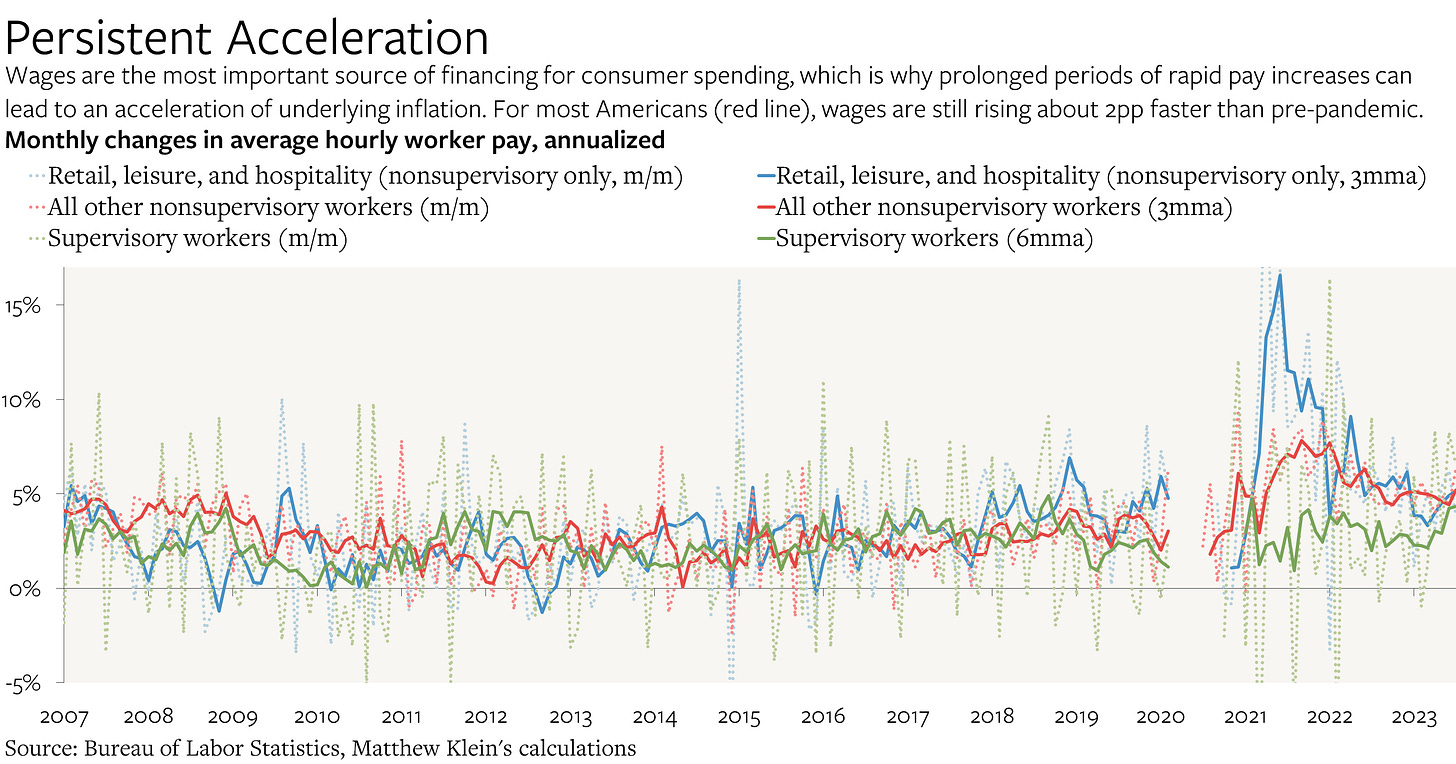

In this context, focusing on the upside risks to inflation might seem churlish. But it remains extremely difficult for me to reconcile persistent per-worker income growth of ~5% a year with any credible forecast of ~2% inflation.

I laid out the argument in a recent column for the Financial Times, as well as some of the potential implications for asset prices (do read the whole thing):

Just as investors and policymakers were right to look through the “transitory” inflation of 2021-2022, they should also strip out the “transitory” disinflation of 2022-2023 to get a handle on where such pressures will settle in the years ahead. Since inflation is just the difference between changes in nominal spending and real production, that means focusing on wage trends: the largest and most reliable source of financing for consumer spending…This explains Fed officials’ continued focus on “softening” the job market via higher interest rates. That presents a risk that interest rates may not come down as quickly as implied by market prices, which in turn could affect other asset valuations.

When people get more money, they usually end up spending it. If businesses can ramp up their production of goods and services commensurately, there is no impact on prices. If not, then the extra income is fuel for inflation.

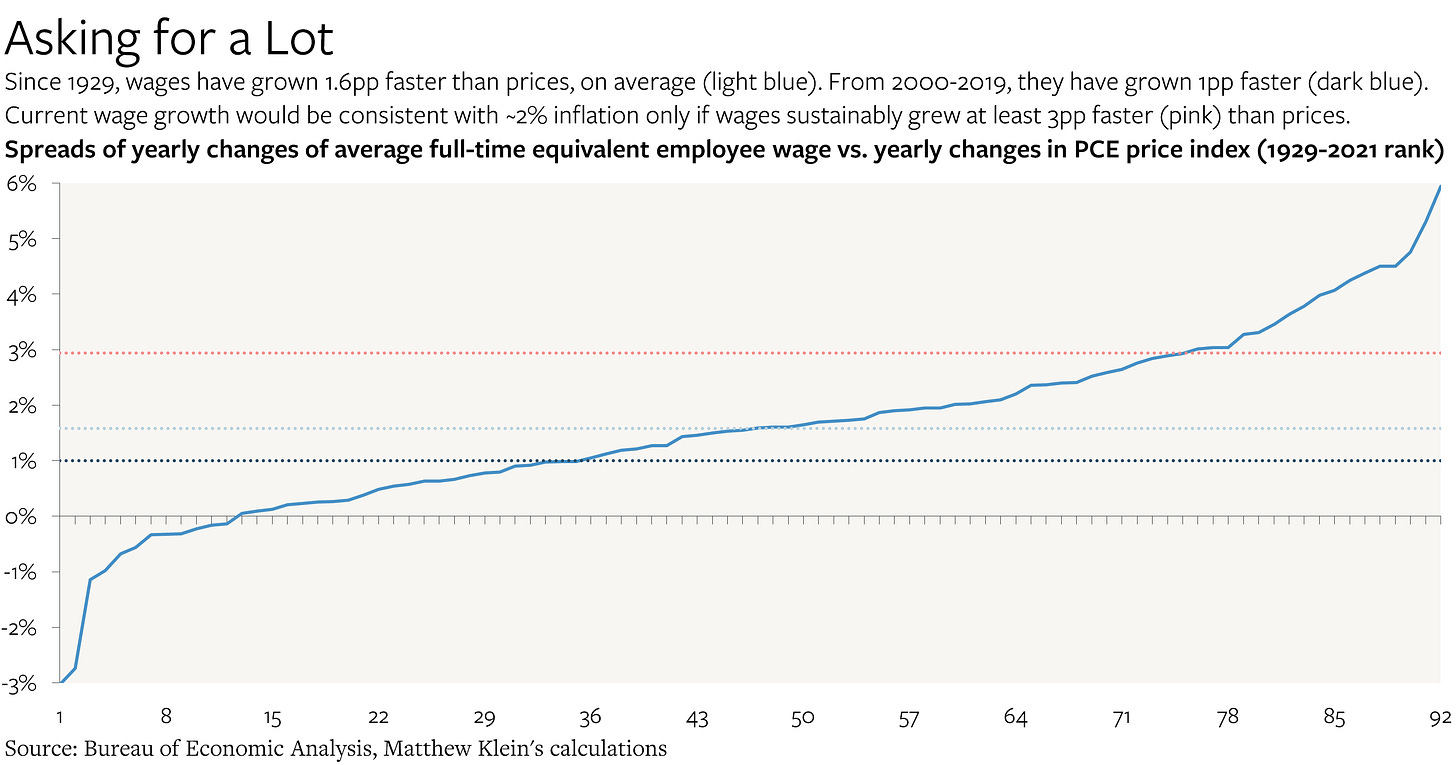

As I have pointed out before, we have yearly data on both the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) price index and average wage income per full-time employee going back to 1929. From 1929 through 2021, wages have grown about 1.6 percentage points faster than prices each year, on average. From 2000 through 2019, the average spread was just under 1%. There is plenty of variation year-to-year, and there have certainly been times when wages have grown at least 3 percentage points faster than prices, but those episodes have been exceedingly rare, especially since the mid-1950s.

Of the 92 years for which we have data, wages have grown at least 3pp faster than prices in only 17 years, most of which were during the Great Depression, WWII, and the Korean War. Exclude 2020—when average wages were inflated by the mass layoffs of lower-paid workers—and there were only five years since 1956 when wages rose at least 3pp faster than prices: 1964, 1968, 1972, 1998, and 2000.

To be clear, it is not impossible for wages to rise 3pp faster than prices over a multi-year period. American workers could choose to use an unusually large chunk of their incremental earnings to buy financial assets—or pay down debt—rather than goods, services, or housing. Latent untapped productivity gains could help businesses expand output without putting pressure on prices. Crises or policy errors in the rest of the world could depress global demand for goods and services, thereby freeing up the supply available for Americans (at the cost of rising indebtedness to foreigners and downward pressures on the incomes of American producers).

Personally, I would be thrilled if persistent supernormal wage gains made it possible for Americans to de-lever, build wealth, and shift the distribution of income from the ultra-rich and the companies they control to ordinary people. It is even possible that higher interest rates and cheaper (eventually) asset prices would help encourage this by raising the prospective returns of saving relative to consuming. I would also love to see investment subsidies, cheap energy, and the hard lessons of the pandemic break us out of the multi-decade productivity slowdown that has held back living standards in the U.S. and around the world.

As welcome as those scenarios would be, however, I fail to see why they would be the likeliest outcomes. It seems more likely that consumers will simply choose to keep spending what they earn to buy the things they want without needing to rely on excessive borrowing, while productivity remains on its unimpressive but upward-sloping longer-term trend.

That is not a bad outcome by any means, but it is one where the apparent disconnect between wages and prices would be resolved in favor of persistently (slightly) faster inflation. As I put it in the FT:

Many Fed officials would be unwilling to force the economy into a downturn just because inflation stabilised around 4 per cent a year, instead of 2 per cent. It was not long ago that many leading economists were recommending 4 per cent inflation targets, or, in what amounts to roughly the same thing, a 5 to 6 per cent yearly nominal income growth target. But while a policy of benign neglect might make sense, it is not currently priced in.

If you find the arguments in the linked papers persuasive, this inflation reset would be a substantial improvement relative to what we have been trained to expect from living through the 2000s and 2010s. I am not sure that I am persuaded, but I am confident that the policy regime that preceded the pandemic was a failure that forced hundreds of millions, if not billions, of people to live below their means. We should welcome the emergence of something different.

Federal Reserve economists found that the shift in spending (think more home renovations vs. nights on the town) “explains a large portion of the rise in U.S. inflation in the aftermath of the pandemic” above and beyond any increase in the total amount of spending. That makes sense, as total consumer spending from January 2020 through June 2023 ($56.5 trillion) has only been 2.4% higher than what would have been expected based on a naive extrapolation of pre-pandemic trends ($55.1 trillion). Yet the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price level in June 2023 was 8.4% higher than what would have been expected based on the pre-pandemic trend. In the case of market-based consumer spending excluding groceries and energy, the cumulative amount spent since January 2020 is exactly what would have been expected, yet the price level is 7% higher.

The PPI does not line up perfectly with the CPI because they measure different things. U.S. companies sell goods and services to other businesses, to foreigners, and to the government, while the CPI only tracks consumer purchases. Similarly, American consumers buy goods and services from both American and foreign businesses. The largest component in the CPI, by far, is residential rents, which is not in the PPI at all. Then there is healthcare, which is notorious for opaque layers of intermediaries who stand between the prices charged by providers (PPI) and experienced by patients (CPI).

Two sides to this argument. One could argue that wages are a lagging indicator and that current wage increases are reflective of past inflation. There is another side though and wage growth does mirror recent interest rate increases in the intermediate to longer term tenors in the treasury market and recent rises in commodity prices. Possibly we're experiencing the end of the post GFC "savings surplus" and the onset of above trend (since the GFC) growth on the demand side. We shall see.

When you mention American Consumer de-levering, what're the primary sources of American Consumer leverage (not counting mortgage, I assume)? Credit cards?