Australia Is Raising Rates. Why Not the Fed?

The U.S. economy is accelerating, yet policymakers are still unreasonably concerned about downside risks.

Based on the data we’ve seen and the conditions here and around the world, the Board now thinks it will take longer for inflation to return to target and this is not an acceptable outcome…Our updated view, driven by the latest data is that demand was stronger than expected over the second half of 2025 and we think some of that strength has carried into 2026. That strength has also meant that conditions in the labour market have held up well and unemployment has remained lower than thought…the global economy has turned out to be much more resilient than we thought despite the ongoing high level of uncertainty and unpredictably. And finally financial conditions have eased, and it is uncertain now whether they remain restrictive overall.

—Michelle Bullock, governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia (February 3, 2026)

Australia is a world away from the U.S., and the forces affecting its economy are often different from the ones on the opposite side of the planet. But Americans could learn something from the RBA’s recent about-face, because in this case, the circumstances are remarkably similar. The latest data imply that fears of U.S. economic weakness were overdone. If anything, cyclical sectors, including construction and manufacturing, have begun to re-accelerate. And all of this is happening as inflation remains persistently faster than the Federal Reserve’s ostensible 2% target, especially when focusing on measures that better reflect underlying demand. That should have implications for monetary policy, as it did in Australia.

Before digging more into the U.S. numbers, it is worth briefly examining what happened down under.

Behind the RBA Pivot

Australia had a relatively good pandemic, with far fewer deaths than in most other countries, as well as a vigorous rebound in economic activity. In fact, real Australian domestic spending grew substantially faster in 2019Q4-2022Q4 than in 2016Q4-2019Q4.1 Since the end of 2022, inflation-adjusted domestic final demand has continued to rise faster than it did in the pre-pandemic period, thanks in large part to faster growth in housing construction and business investment.

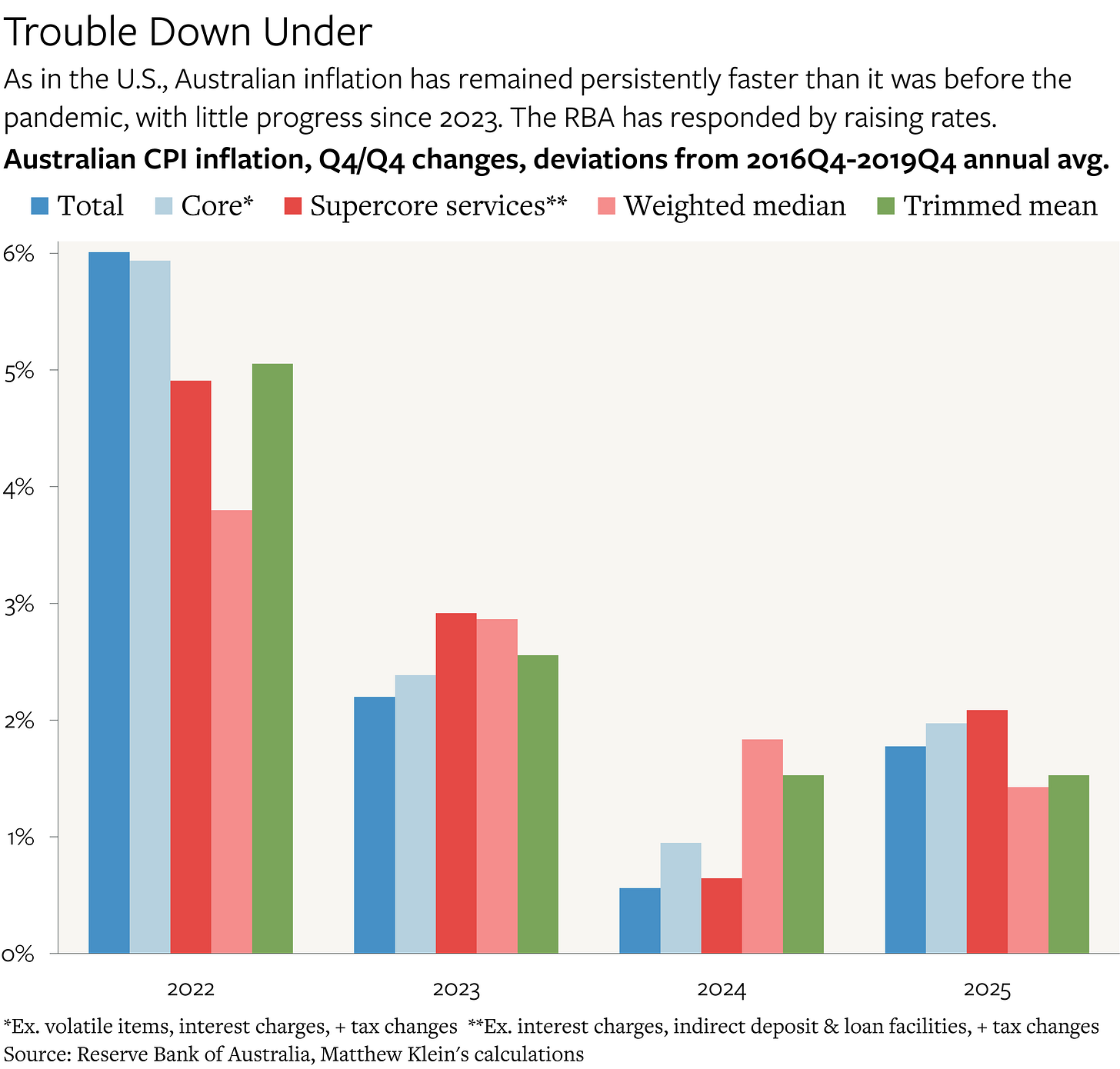

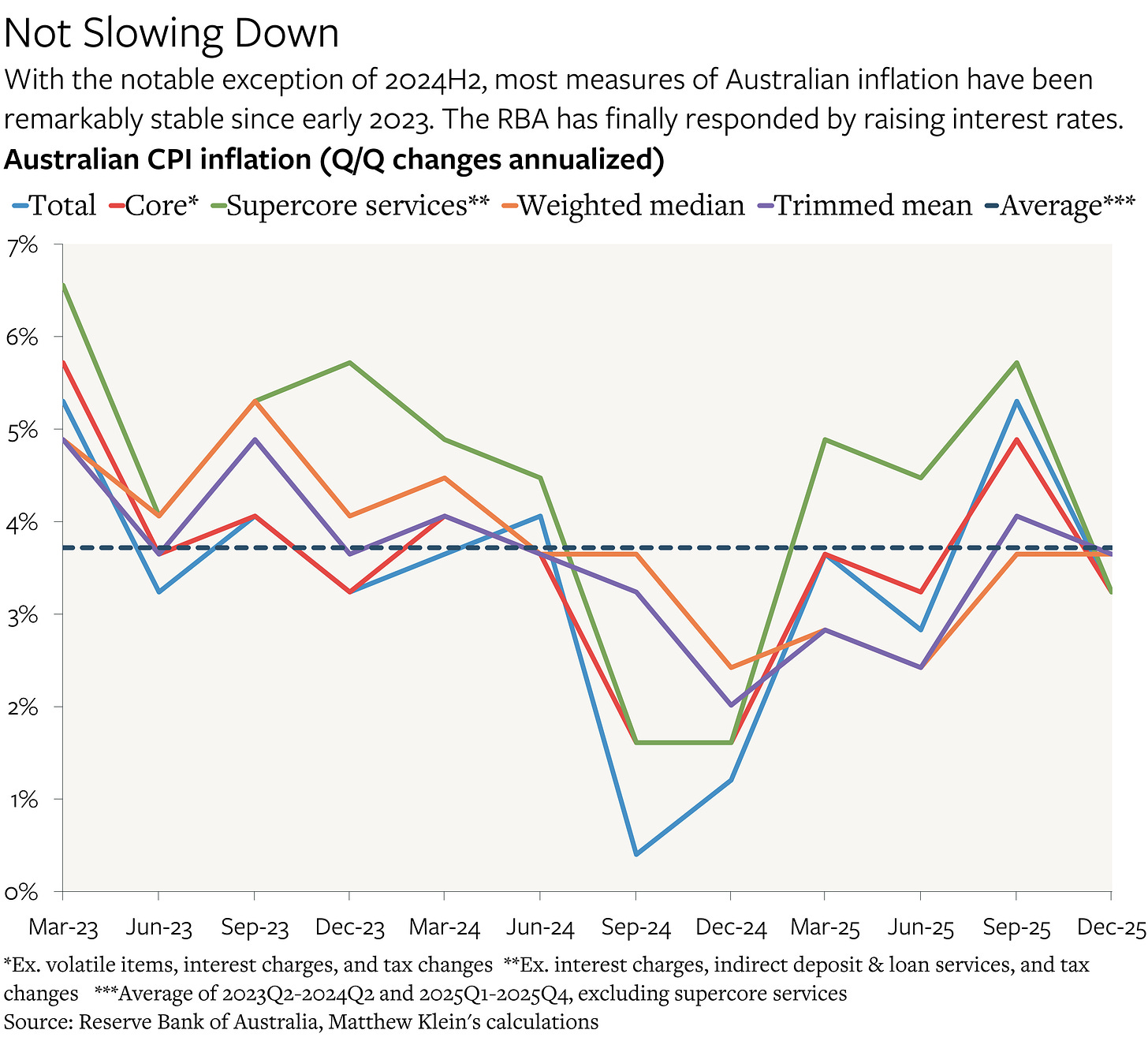

Nevertheless, Australia was still affected by the post-pandemic inflation shock that hit the rest of the world. Annualized inflation peaked in 2022, as in many other countries, at about 8% a year. As in the rest of the world, inflation decelerated sharply from that peak. But, as in the U.S., Australian prices since then have been rising modestly but persistently faster than in the years before the pandemic—and faster than the central bank’s target. With the odd exception of the second half of 2024, when prices barely rose at all, the growth rate in Australian prices has consistently averaged about 3.7% a year ever since the beginning of 2023.

That is not that much faster than the RBA’s target of 2.5% (technically the midpoint of the range between 2% and 3%) but RBA officials are evidently concerned by the lack of progress, especially after having been tricked by the misleading slowdown in inflation in 2024H2 into lowering the cash rate by 0.75 percentage points in 2025H1.

Part of the reason why the RBA was willing to start lowering rates was that the job market had been gradually weakening. Similar to the U.S., the Australian unemployment rate hit a multi-decade low of 3.5% at the end of 2022 / beginning of 2023. Since then, as in the U.S., the Australian jobless rate has been grinding higher. This occurred in two distinct moves. First, unemployment rose to 4% by the end of 2023, and stayed there through the end of 2024. Then unemployment began rising again, reaching 4.4% by September 2025.

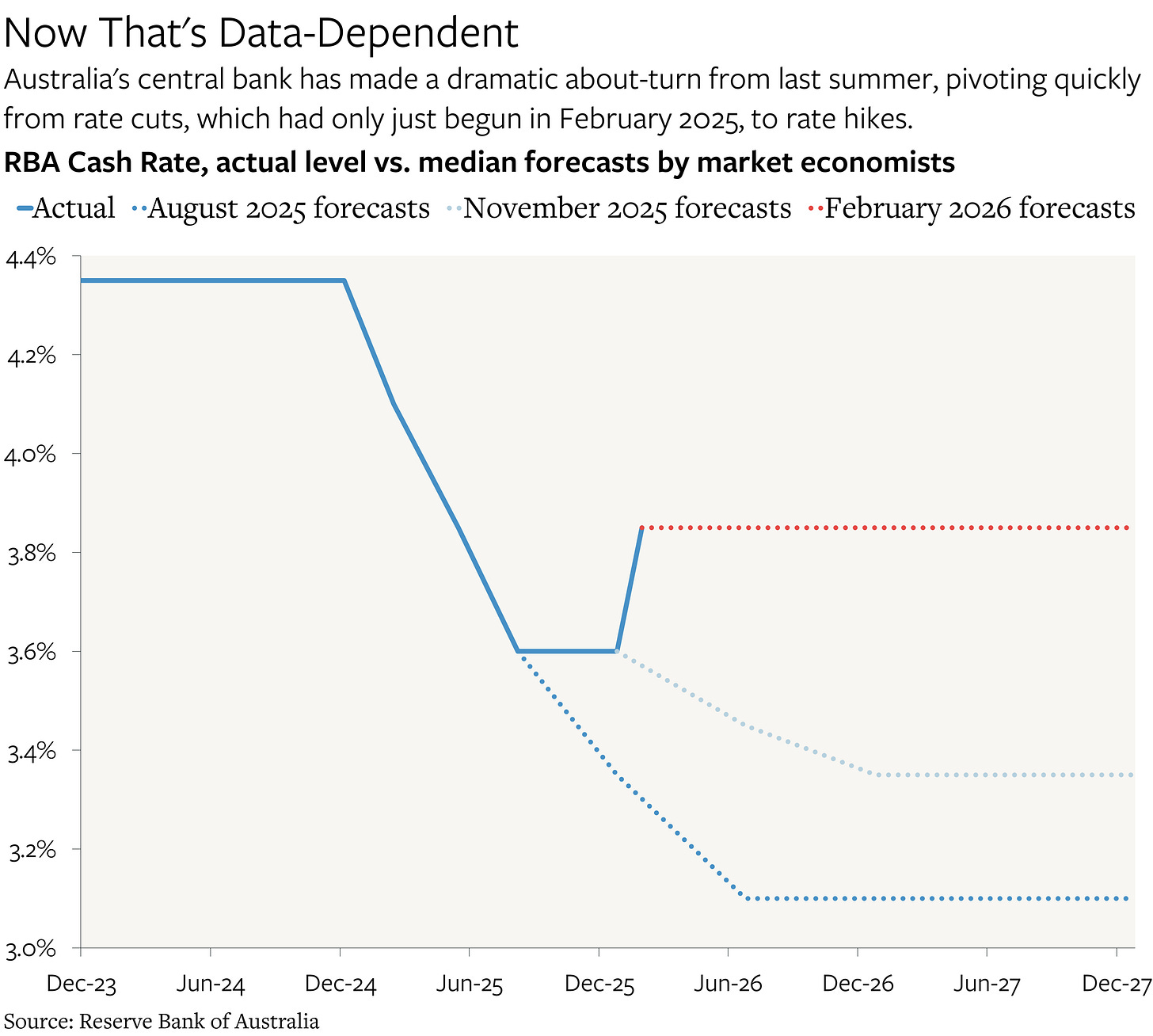

Compared to the Fed, the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of England (BOE), the Bank of Canada (BOC), the Bank of Korea (BOK), or the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ), the RBA was relatively late to begin lowering its policy rate, with the first cut occurring in February 2025. Until then, the modest weakening of the job market was not enough to justify a change in policy, especially as long as inflation was coming in relatively hot. Once inflation appeared to decelerate—at the same time that the job market looked to be rolling over, no less—RBA officials thought that conditions finally justified lowering rates.

But it turns out that this was an illusion. Not only did inflation quickly revive, so did employment. As of December 2025, the unemployment rate was back down to 4.1%. Meanwhile, Australia’s nominal wage growth has consistently been coming in around 4.5% a year, compared to about 2.5% a year before the pandemic. Just as in the U.S., the modestly faster trend in wages has corresponded with a modestly faster trend in prices.

To give credit where due, the RBA has been quick to change course, having last lowered the cash rate as recently as August 2025 and, at the time, having convinced RBA-watchers that the cash rate would continue to drop by another 0.5 percentage points by the middle of this year. Forecasts have changed accordingly.

The Fed may not end up following the RBA’s example, especially if the current administration succeeds in suborning the central bank, but there are good reasons for policymakers in America to consider following their colleagues down under.