The Fed Submits?

America's central bankers have, in the aggregate, lowered the "appropriate" path for interest rates despite an improved growth outlook and a worsening inflation picture. There is no good explanation.

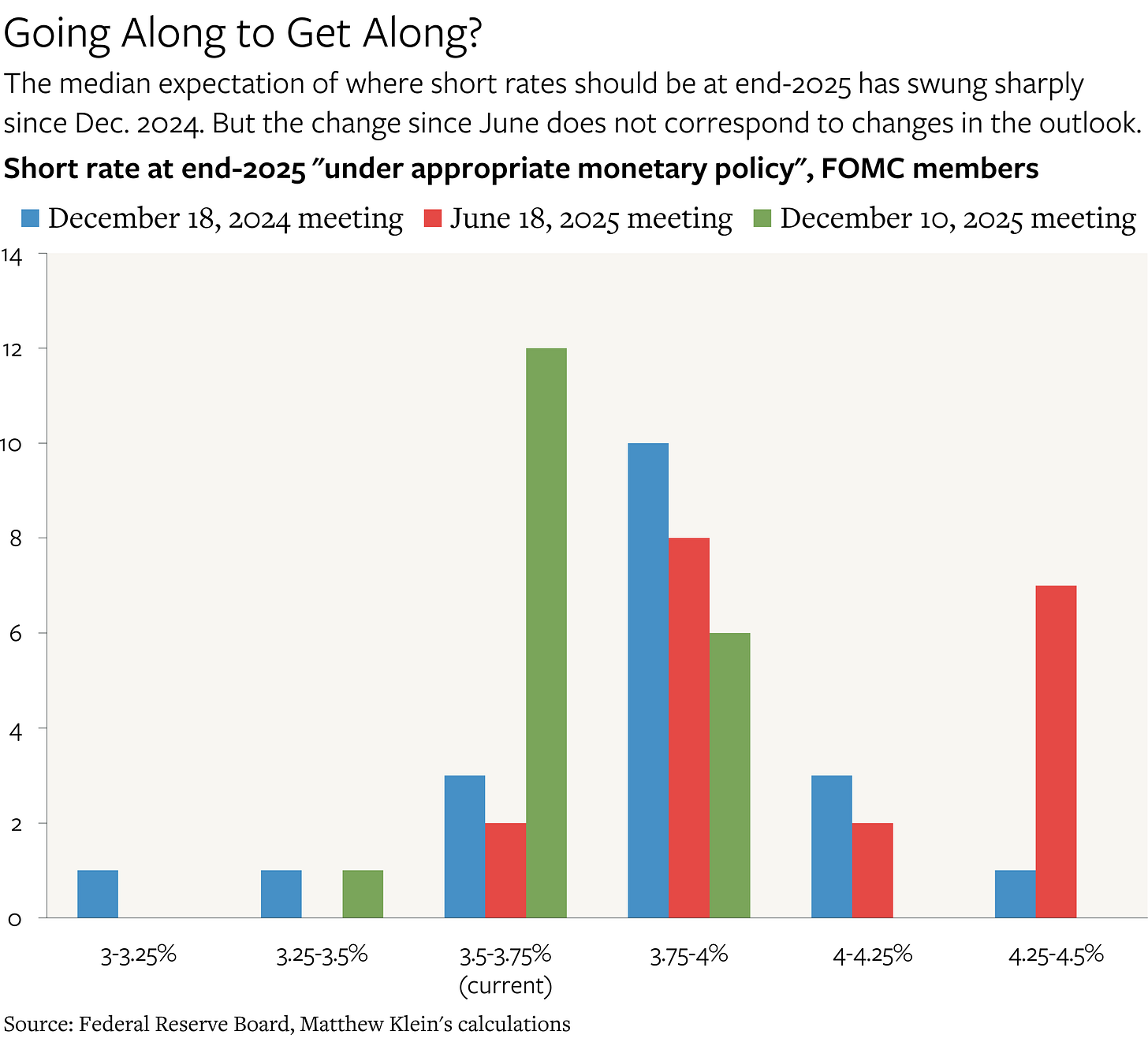

Federal Reserve officials are more optimistic about the growth outlook, less worried about unemployment, and just as worried about inflation as they were six months ago. Yet the median official now expects that short term interest rates “under appropriate monetary policy” will be lower than what was expected in June through at least 2027.

For the most part, this shift cannot be explained by changes in the underlying economic data, to the extent that we have it. (While the statistical agencies will eventually catch up, the federal government shutdown has ensured that most of the numbers available as of this writing only run through September.) The more plausible explanation is that a small but growing cadre of Fed officials have been reinforcing the pressure from administration officials for larger and faster reductions in interest rates. Against them is a sizable contingent of Fed officials—consisting mainly of the reserve bank presidents, who are somewhat more insulated from Washington politics—that is resisting the attempt to suborn the central bank.

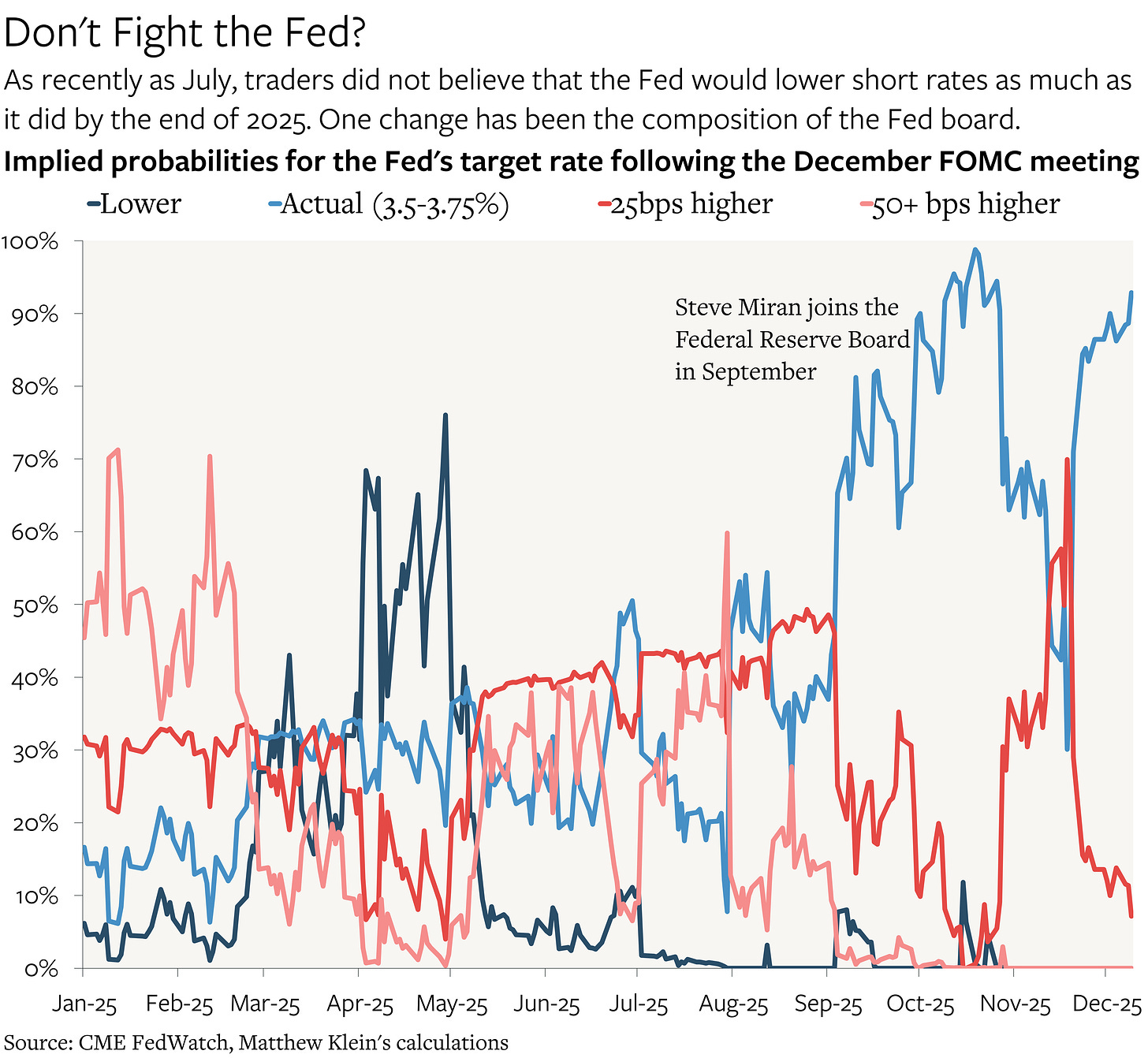

So far, the latter camp has been fighting a rearguard action. The target band for short-term interest rates has already dropped by 0.75 percentage points just since September (to 3.5-3.75%), even though, as recently as July, traders had been betting against most, if not all, of those cuts, in line with what Fed officials had been saying.

From this perspective, the apparent preferences of the median official may not be particularly helpful for anyone trying to understanding how Fed officials as a group will actually respond to changes in the outlook. Instead, what matters most are changes in the relative size and strength of the emerging voting blocs within the Fed. Abstract institutional preferences matter far less than the choices of the specific individuals empowered to make decisions, and those decisions may be affected by external pressure as much as anything else.

What follows is a closer look at the shift within the Fed over the past 12 months and how it corresponds—or fails to correspond—to changes in the data.

The Dashed Dreams of 2024 (in 2025H1)

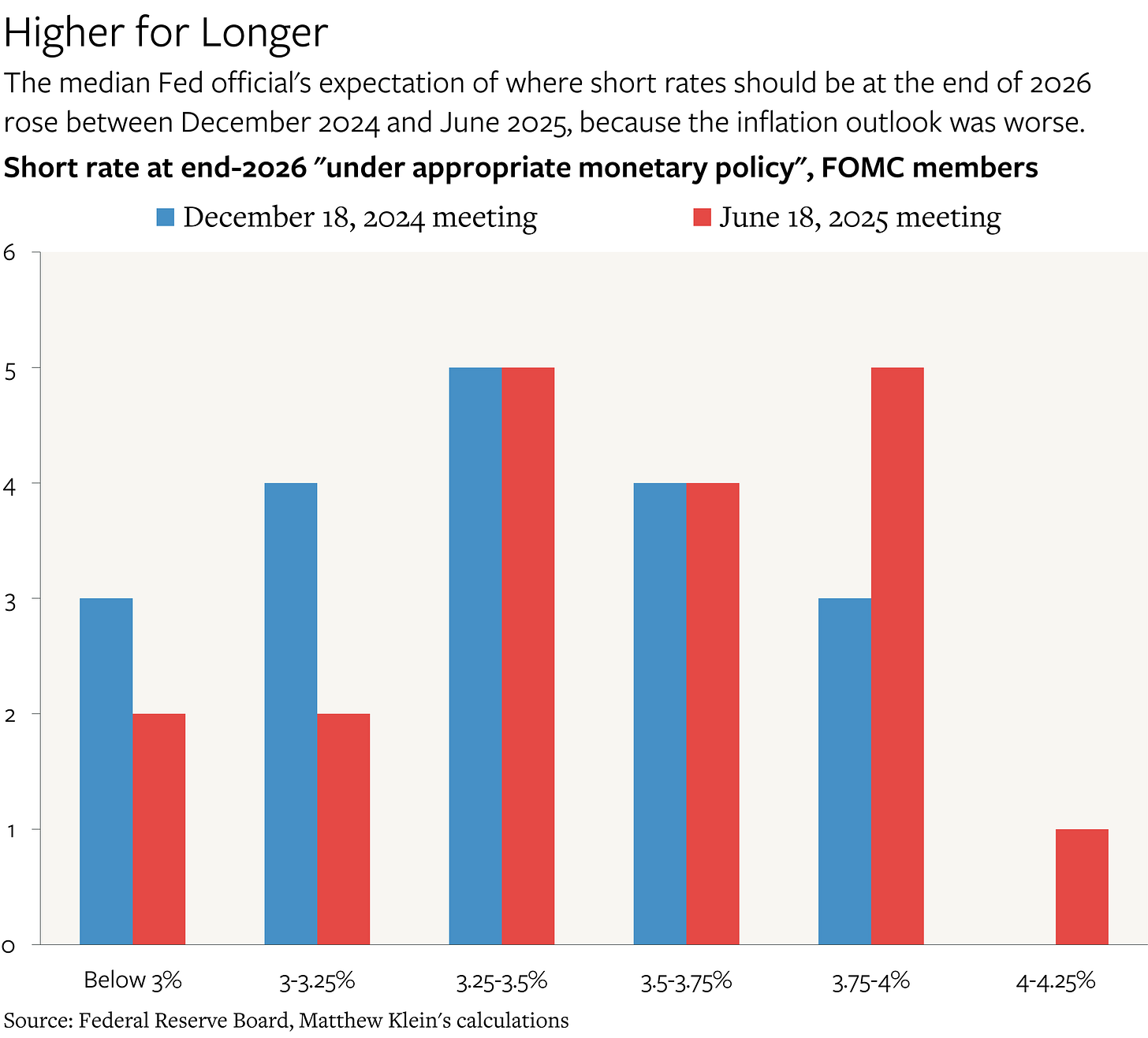

At the end of 2024, Fed officials were optimistic. “Under appropriate monetary policy,” excessive inflation would be essentially over by the end of 2026, and this would occur without unemployment rising and without any hit to real growth. Back then, the assumption of most officials was that short rates would need to be between 3.75% and 4% at the end of 2025 (0.25 percentage points higher than now), would not need to change much throughout 2026 “under appropriate monetary policy”, and then maybe fall slightly by the end of 2027.

A few things have happened since then.

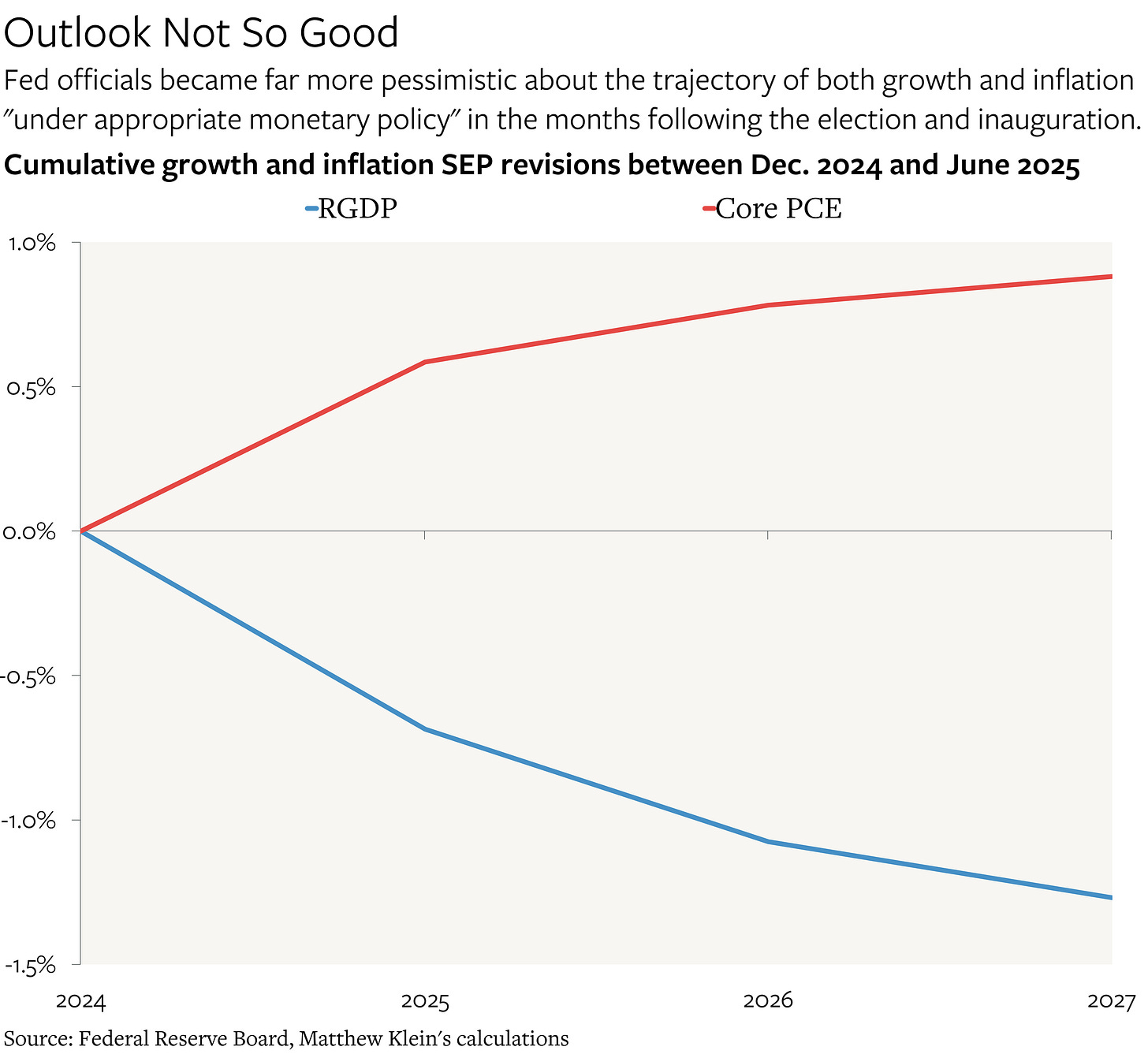

By March—before the announcement of the “liberation day” tariffs, but after the new administration had already demonstrated its intent on everything from antagonizing Canada and Mexico to slashing support for scientific research to attacking law firms—Fed officials had concluded that Americans would be poorer even under the most benign scenario, with consumers paying higher prices while enjoying fewer goods and services. “Appropriate monetary policy” did not change (much) from December 2024 to March 2025, because Fed officials’ unemployment outlook did not change, but that was essentially a coincidence.

By June, the picture had become clearer (and worse). The risks to growth were slow-moving and secular, but unlikely to have much of an immediate cyclical impact.1 The risks to inflation, however, were both short-term and long-term. Tariffs and other supply disruptions attributable to policy choices were pushing up goods prices. More worryingly, these “one-off” disruptions were occurring at a time when underlying inflation was still running faster than the Fed’s 2% yearly target and at a time when consumers, workers, and businesses had already become primed to react, if not overreact, to changes in prices by adjusting their behavior in ways that would only reinforce the inflationary impulse.2

The implication, back in June, was that nominal interest rates would have to be somewhat higher “under appropriate monetary policy” to prevent inflation from getting competely out of control.

Even then, Fed officials expected that Americans would have to endure an additional 1% increase in the price level by the end of 2027 relative to what had been expected back in December 2024, while the real volume of goods and services produced in the U.S. would be 1.3% lower. Fed officials also thought that unemployment would have to be slightly higher “under appropriate monetary policy”, although they hoped that they could hold the line at 4.5%.

The Revival of Confidence and the Asymmetric Policy Response (in 2025H2)

Since then, Fed officials have become far more optimistic about the real growth outlook, although they have not gotten more optimistic about inflation “under appropriate monetary policy”. The net result is that the real volume of goods and services produced in the U.S. is now expected to follow essentially the same trajectory that had been hoped for back in December 2024, despite everything, while the price level will be higher.