Back to Square One on the Russia Sanctions?

As Russia's import volumes hit new highs, the allies are now compelled to try different approaches, from targeting third countries with sanctions to capping the price of Russia's oil exports.

Wars are not always won by the side with the greatest access to commodities and advanced manufactured goods, but that’s the safe way to bet.1

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine initially seemed destined to succeed precisely because of the aggressor’s apparent advantages in materials and materiel.2 Yet more than a year later, the Russians have not only failed to subdue the Ukrainians but they are even in danger of losing the territories they conquered in 2014. While much of credit must go to the Ukrainians themselves, credit is also due to the considerable economic resources deployed by the global alliance of democracies to tilt the battlefield.

External support has allowed the Ukrainians to sustain their imports of civilian goods despite losing control over substantial portions of their territory, suffering a population exodus, and enduring relentless attacks on their civilian infrastructure. The Ukrainians have also been receiving substantial inflows of increasingly potent weapons—most recently, F-16s and other fouth generation fighters—to compensate for deficiencies in their domestic production and stockpiles.

At the same time, the allies have squeezed the Russian military by restricting access to critical parts and components necessary to replace lost tanks, missiles, aircraft, and other equipment. As I put it more than a year ago:

While it would be inappropriate for NATO aircraft to bomb Russian tank factories, shipyards, and missile assembly plants today, it would also be unnecessary. The democracies can replicate the effect of well-targeted bombing runs with the right set of sanctions precisely because the Russian military depends on imported equipment from the very same set of countries it has angered with its brutal attack on Ukraine.

This has clearly had an impact, with the Russian business press regularly publishing stories on how shortages of imported goods are affecting everything from helicopter maintenance to trucking.

The net effect is that the material balance has shifted in favor of the defenders.

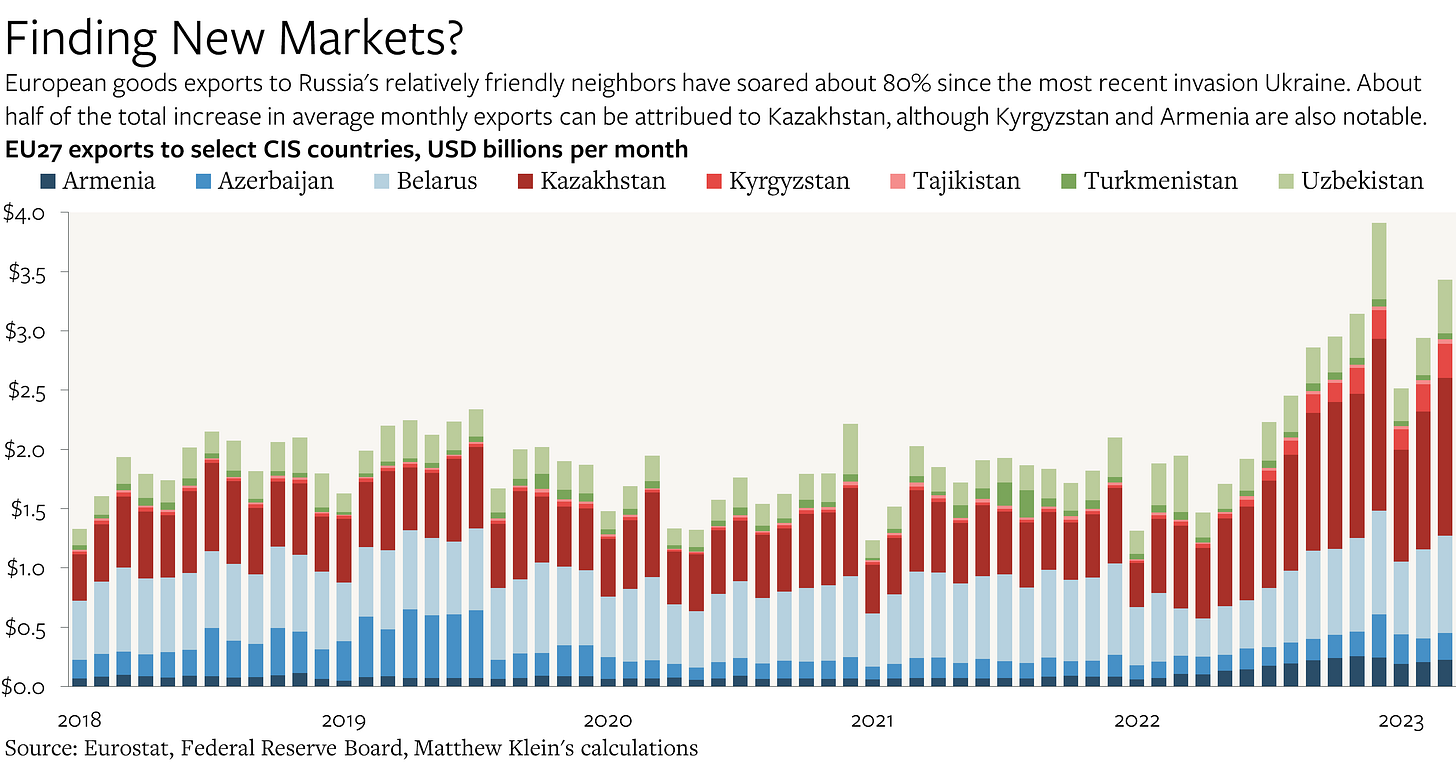

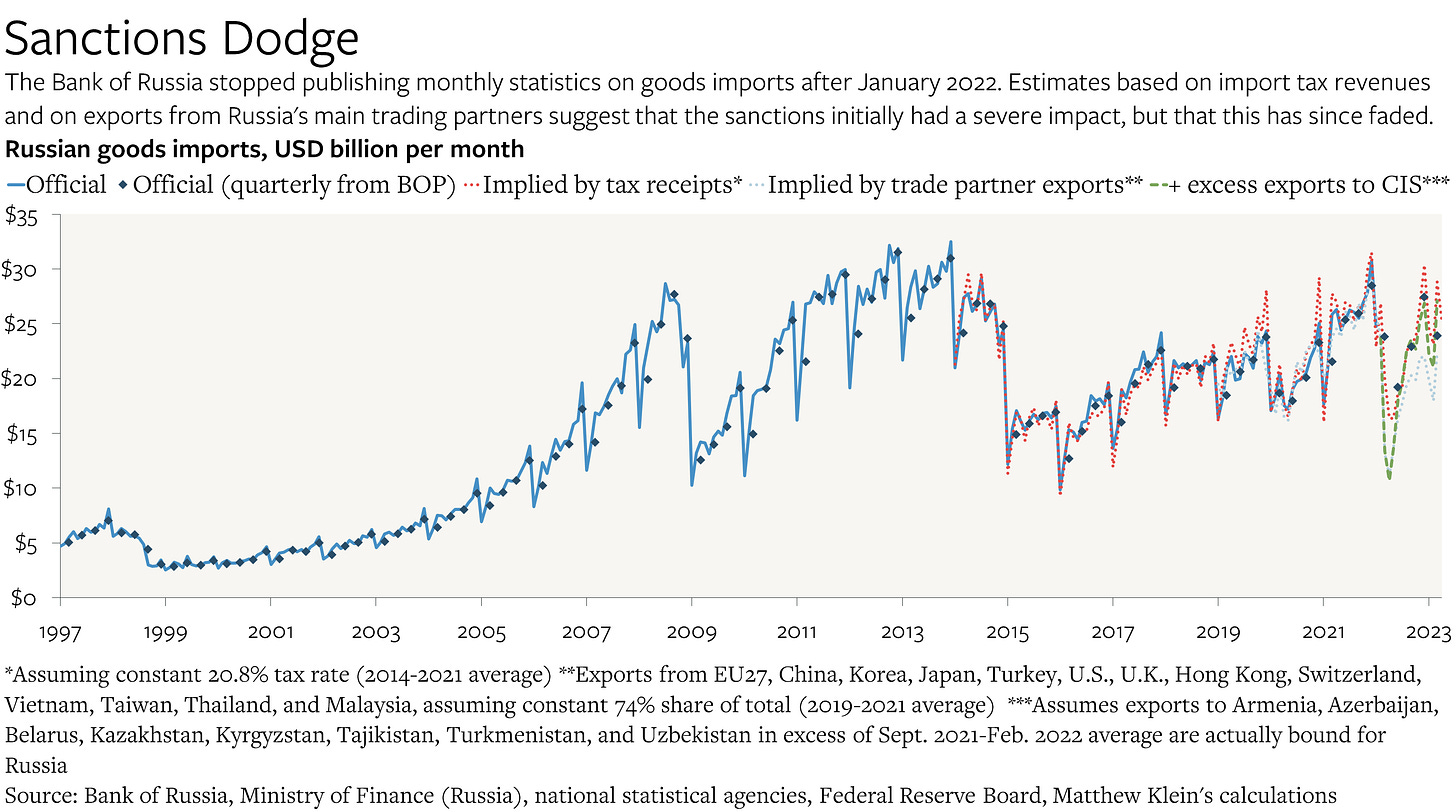

Unfortunately, the trade restrictions that had been so effective in the initial months of the invasion have become increasingly porous. Exports from many jurisdictions directly to Russia have rebounded at the same time that exports to Russia’s relatively friendly neighbors—which then get re-exported to Russia—have soared. While the Russian government no longer publishes monthly trade numbers, the data available imply that Russian imports of goods have returned to pre-invasion levels.3

Policymakers are aware of the problems, which explains why some Europeans are looking for ways to ban certain exports to third countries and why the U.S. government is continuing to hunt those who help the Russians gain access to critical parts and components for weapons.

Nevertheless, there are clear limits on (some) allies’ willingness to do more. When U.S. officials proposed an embargo on most goods sold to Russia ahead of the G7 meeting, their European and Japanese counterparts refused. Since they declined to explain their positions publicly, I can only speculate that those governments are prioritizing their businesses’ export markets over Ukrainian lives. This is an absurd choice—and an entirely avoidable one, as I explained over a year ago with Jordan Schneider and David Talbot—but it appears to be the choice they are making.

Back to the Beginning?

Instead, the allies seem to be focusing on new measures to restrict imports from Russia, most notably the price cap on Russian crude oil, which took effect earlier this year. The theory is that reducing Russian hard currency earnings will force Russians to cut spending on imports and also put a hole in the government’s budget. These sorts of measures were often proposed at the beginning of the war as alternatives to the sanctions that were initially enacted.

From one perspective, the oil price cap is clearly working: Russia’s export earnings in 2023Q1 were 35% lower than in 2022Q1, while federal revenues from oil and gas taxes in January-April 2023 were 48% lower than in January-April 2022 (in USD).

But this has yet to translate into the outcomes that matter.