Is Japan "Normal" Again?

After decades of trying, it looks as if inflation and nominal income growth have finally reset to a new, faster baseline. That explains the actions in bond yields, and why the yen has not appreciated.

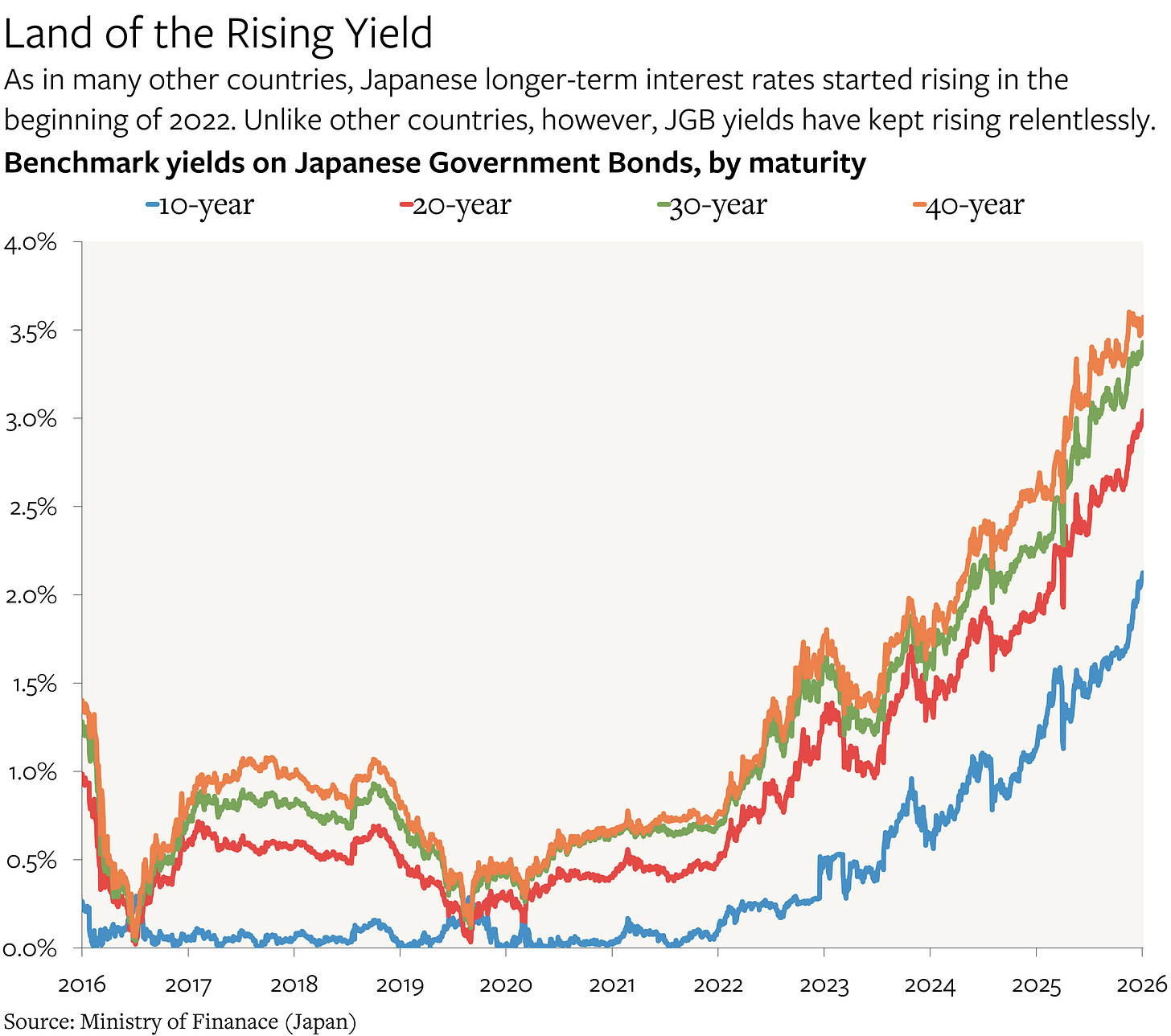

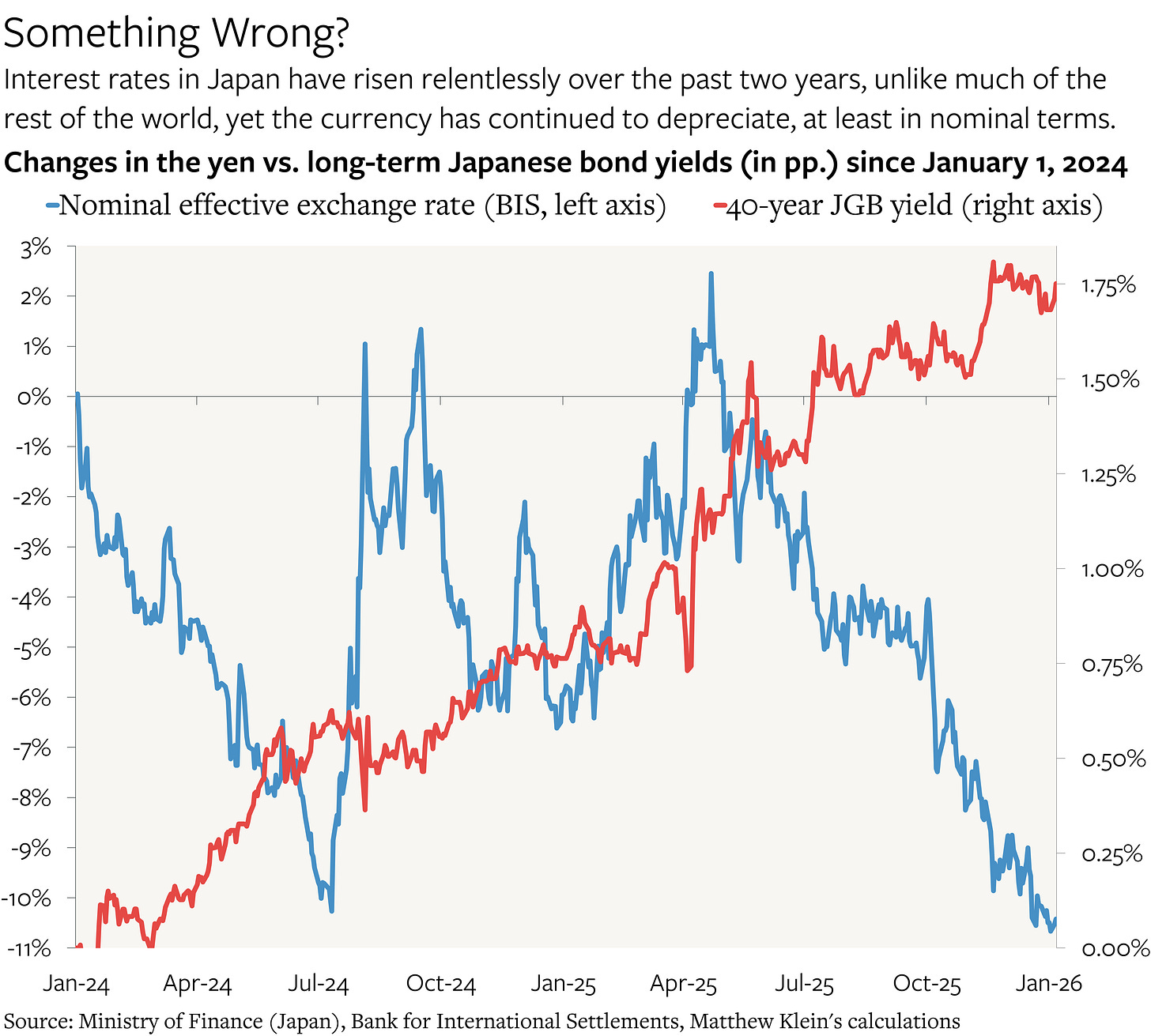

Japanese bond yields have been rising relentlessly over the past few years, especially at the longer maturities that were never directly targeted by the Bank of Japan (BOJ). Yields on long-term Japanese government debts are now higher than at any point since the 1990s. Yet the yen has not only failed to appreciate against the currencies of its trading partners—all of which have experienced either smaller increases in interest rates or falling rates since the middle of 2023—it still looks cheap relative to its history.

At first glance, this seems extremely odd.

Some have argued that the apparent interest rate / exchange rate disconnect can be explained by concerns about the Japanese government’s ability to continue servicing its debts. The central government currently owes about 1.3 quadrillion yen, or about 2x Japan’s national income. As that debt is gradually refinanced at new, higher, interest rates, the budget deficit may get pushed up, leading to even more debt issuance at even higher rates, etc.

Those who believe that the debt is unsustainable believe that the government will eventually be forced to choose between outright default and “debasement” that would cheapen nominal yen claims relative to assets in other currencies as well as relative to real assets. For those who have spent decades warning—or scaremongering—about Japanese public indebtedness, the persistent (nominal) weakness of the yen in the face of rising (nominal) interest rates over the past few years therefore seems like vindication that this process is finally starting.

As of now, however, there is a more benign explanation: Japan may have finally exited its post-bubble stagnation.

The return of modest inflation alongside persistently faster wage and income growth should align with higher interest rates than those that prevailed when the economy experienced essentially no growth in yen terms between 1997 and 2019. Moreover, if the recent growth in nominal incomes is sustained, Japanese government borrowing costs would still be lower, relative to expected revenue increases, than in much of the past few decades. (That helps explains why the yen has not appreciated recently despite the apparent convergence of nominal yields with the U.S. and other G10 economies.) Far from indicating trouble, Japanese bond prices are implying that Japan has converged, in at least one important way, with the rest of the rich world.

The Long Stagnation

Japan’s post-1980s bust was a harbinger of what would afflict much of the rest of the rich world in the 21st century.1

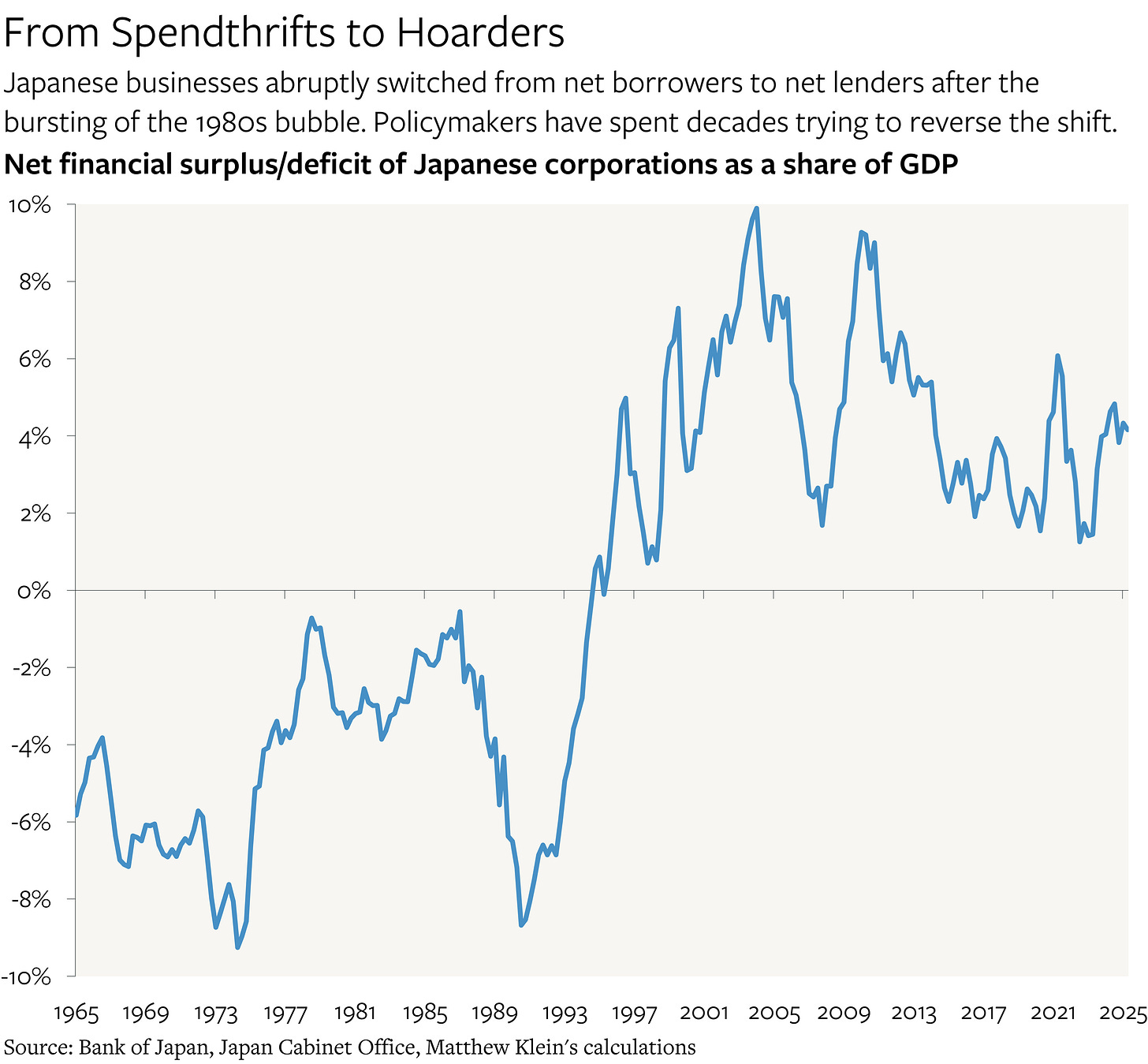

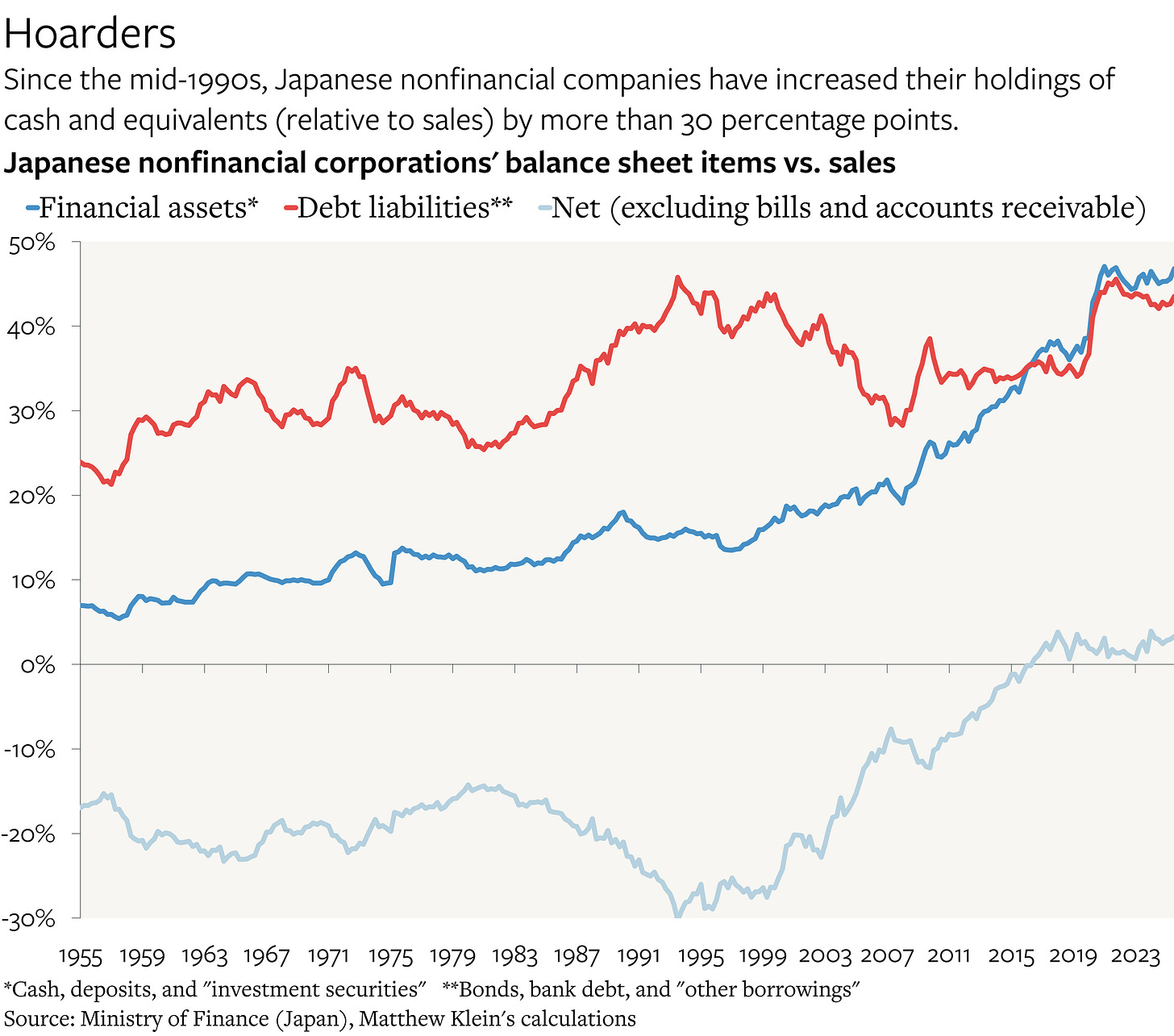

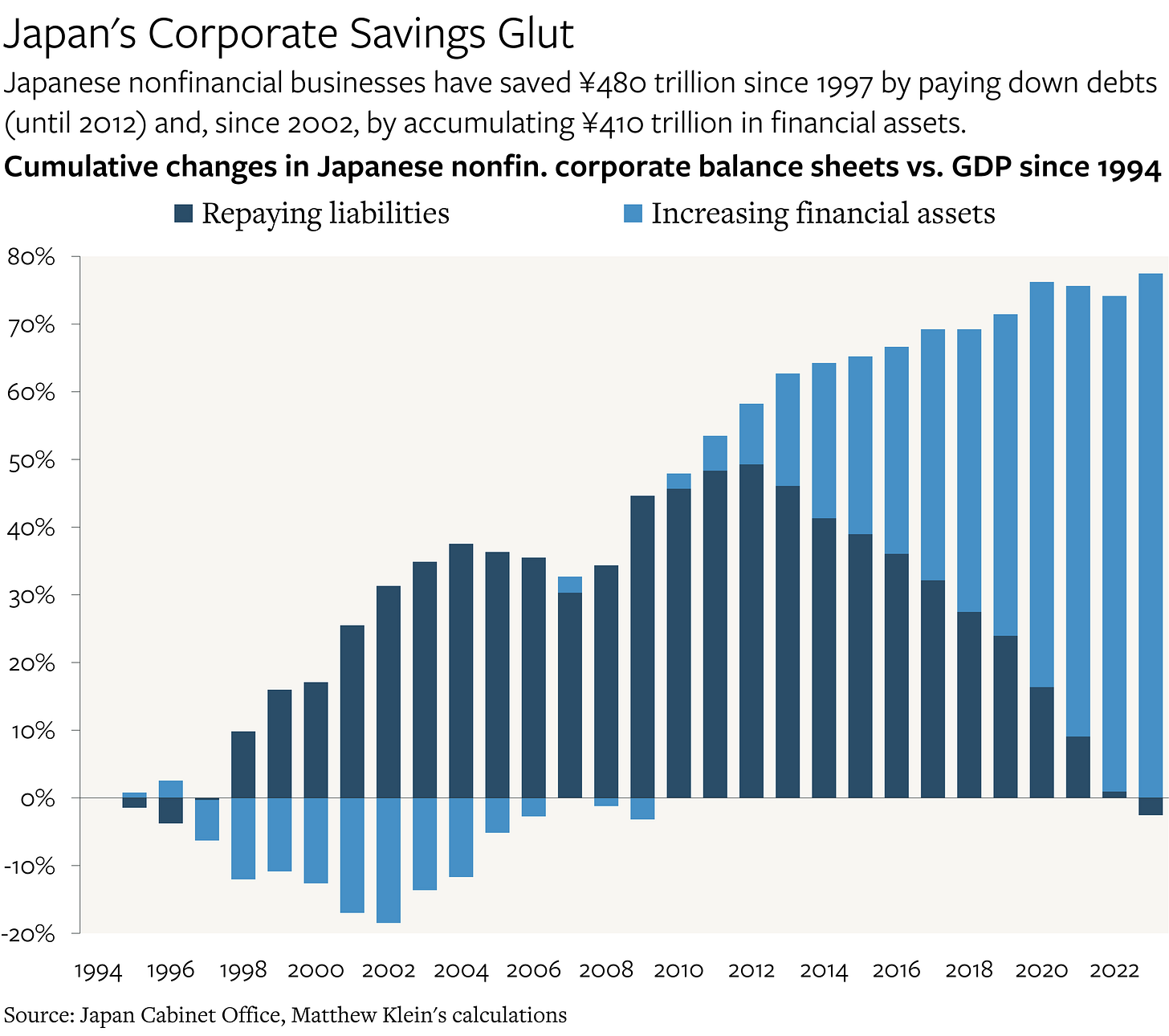

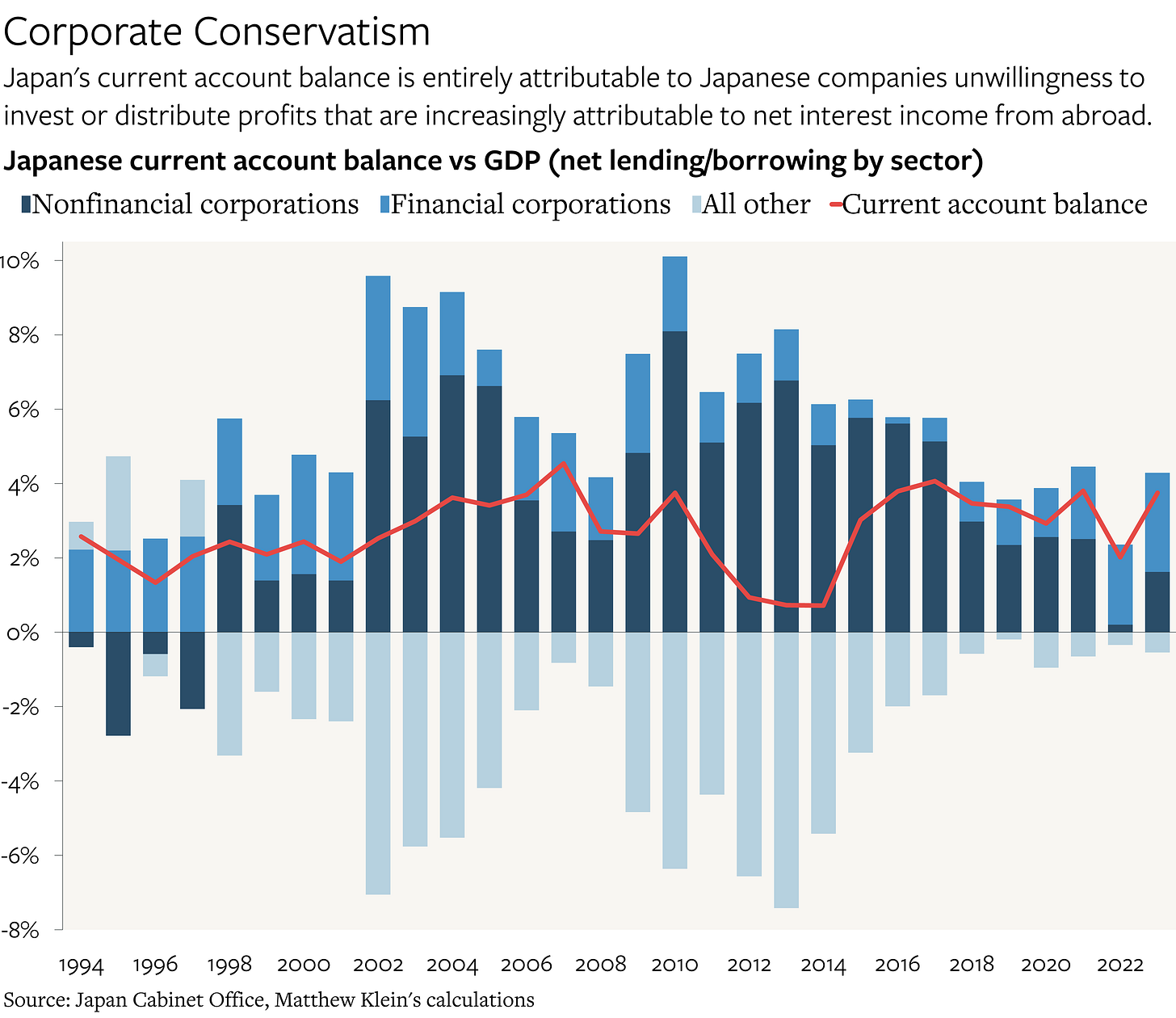

Companies that had borrowed too much in the second half of the 1980s slashed spending in the face of losses, so wage and price growth slowed sharply. Once they finished repaying their debts, they compulsively hoarded cash and equivalents. The Japanese corporate sector swung from a net financial deficit of nearly 9% of national income in 1990 to a net surplus of 10% of GDP by 2003. While the excess of profits over capital spending2 has shrunk somewhat since then, it has remained a large.

As of the end of 2025Q3, the latest available data, Japanese nonfinancial corporations held nearly 1 quadrillion yen in liquid assets, of which ~¥270 trillion were cash and deposits, ~¥233 trillion were bills and accounts receivable, and ~¥460 trillion were investment securities. Net of debt liabilities, nonfinancial corporations’ overall financial asset position relative to their total sales has shifted by more than 30 percentage points since the mid-1990s (or about ¥460 trillion). Put another way, the cumulative net saving of the entire Japanese nonfinancial corporate sector over the past thirty years is currently worth about 80% of Japanese GDP.

Government deficits exploded and public indebtedness soared in response, but it was not nearly enough to restore nominal income to its prior trajectory, so interest rates fell close to, if not below, zero, as Japanese lived below their means.

Japanese policymakers have tried to break this cycle for decades, with the goal of higher corporate investment powering faster wage growth and profit increases that would encourage further investment, raising living standards and boosting tax receipts. Koizumi Junichiro3 hoped that an agenda of deregulation and competition would get companies to spend, but that proved insufficient. More recently, Abe Shinzo and Kuroda Haruhiko had tried to use fiscal and monetary stimulus to change executives’ mindsets. Inflation was not the main goal in and of itself, but was supposed to be a mechanism to encourage capital spending and hiring (or at least shareholder payouts) because it functioned as a tax on corporate cash holdings.

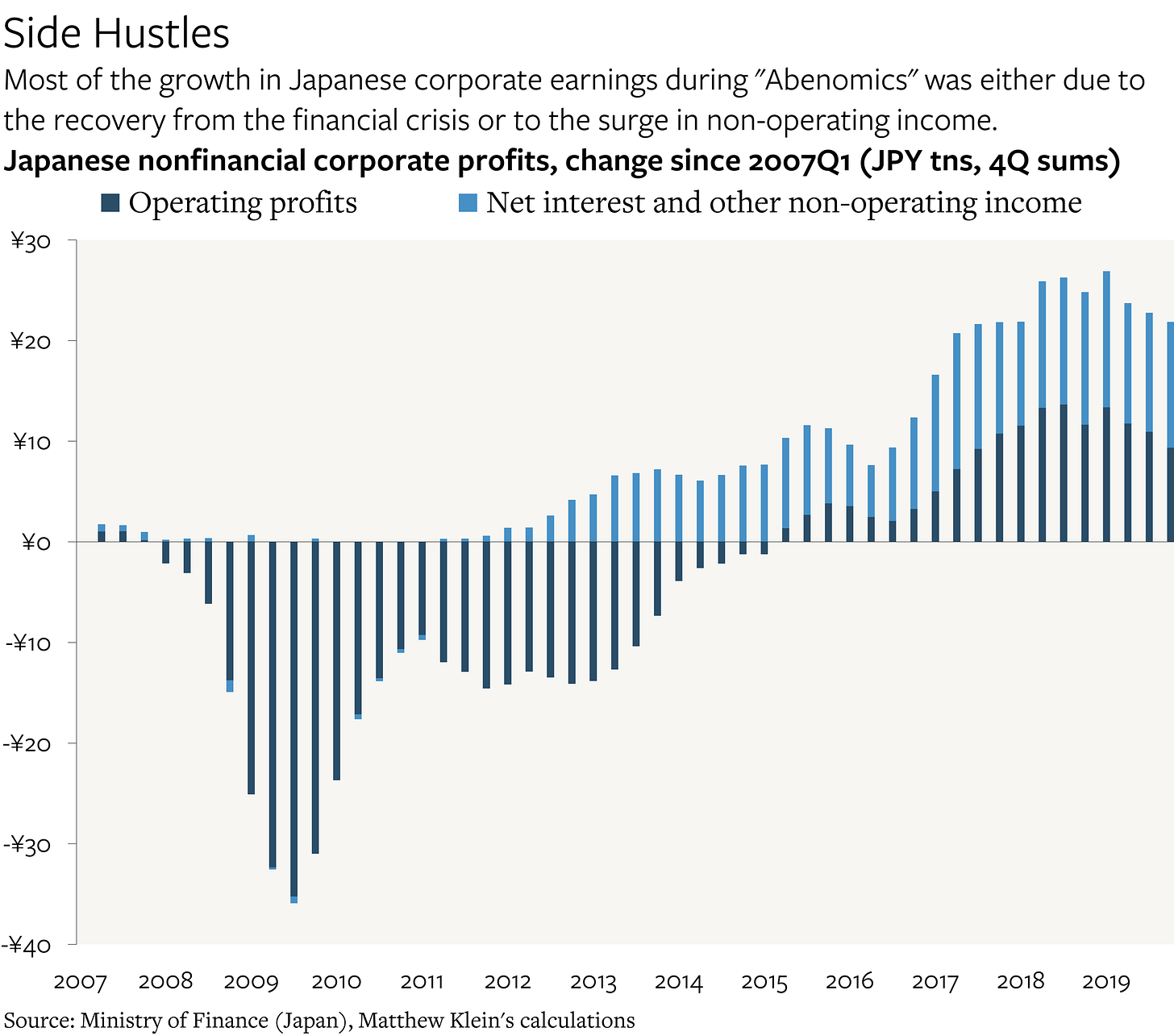

From this perspective, “Abenomics” failed on its own terms, even if it did have a meaningfully positive impact on Japanese stock returns.

Corporate profits surged, but this was largely attributable to windfalls from the depreciating yen and interest rate differentials with the rest of the world. By contrast, Japanese wages, prices, and capital spending all remained stuck in the doldrums on the eve of the pandemic. Even then, profit growth had mostly stalled out by 2017. Japanese corporations outside of finance and insurance earned ¥56 trillion in operating profits in 2007 vs. ¥67 trillion in 2017 (+19%), ¥68 trillion in 2018, and ¥65 trillion in 2019. “Ordinary profits”, on the other hand, which includes net interest income and other forms of non-operating income, rose from ¥60 trillion in 2007 to ¥81 trillion in 2017 (+35%), ¥84 trillion in 2018, and ¥81 trillion in 2019.

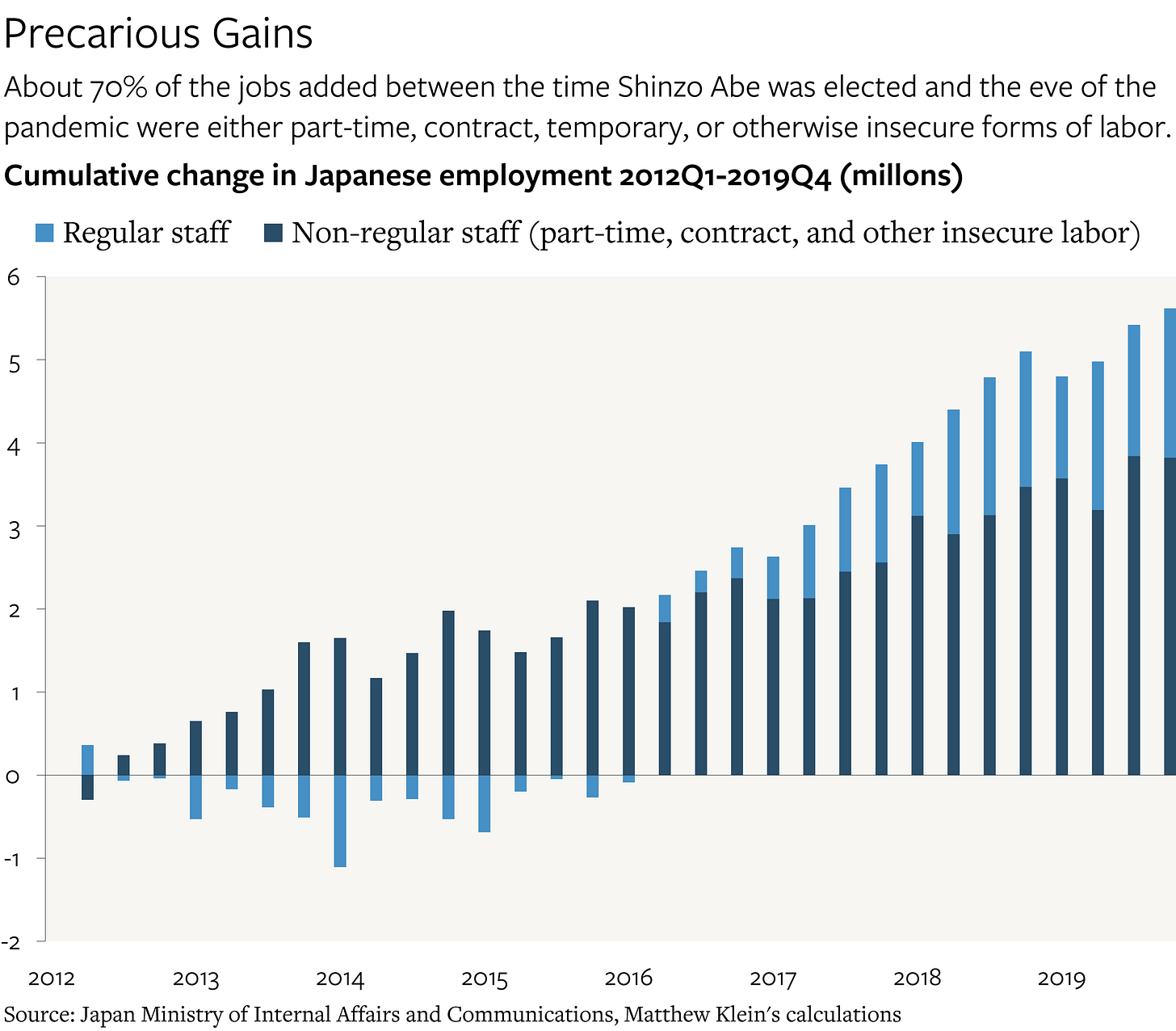

Similarly, while employment had boomed, particularly among women and the elderly, the gains were overwhelmingly in precarious part-time, contract, and other “non-regular staff” positions.

Yet the pandemic and the response to it seem to have broken Japan out of the trap. As in the rest of the world, most notably the U.S., the experience seems to have reset expectations and altered behaviors in ways that should correspond to persistently faster nominal income growth and faster inflation. That should coincide with higher interest rates, especially at the long end. Encouragingly, hiring and investment have also been perking up, which means that the hoped-for passthrough from improved nominal outcomes to improved real outcomes is finally happening.