Is the Fed Preparing to Taper Its Bond Redemptions?

Parsing the links between the Fed, money market funds, commercial banks, and the appropriate pace of balance sheet shrinkage.

The Federal Reserve spent about $4.5 trillion buying Treasury and agency-backed mortgage bonds between February 2020 and April 2022. That portfolio has since shrunk by about $1.3 trillion.1

The question is what happens next.

While all Fed officials agree that the plan is to “slow and then stop the decline in the size of the balance sheet when reserve balances are somewhat above the level it [the Fed] judges to be consistent with ample reserves”, there is now an active debate as to what exactly that means for policy.

A recent speech by Lorie Logan, the influential president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas who had previously been in charge of market operations at the New York Fed, suggests that the Fed may want to slow or halt its balance sheet shrinkage within the next few months. (Recall that Logan’s October speech on financial conditions provided the justification for the Fed to stop raising interest rates.) Others, such as John Williams of the New York Fed, seem more inclined to wait.

Understanding this disagreement—and the implications for markets—requires understanding how the various components of the Fed’s balance sheet fit into the broader financial system, particularly commercial banks and money market funds.

What Fed Officials Are Trying to Do

Fed officials have two related but distinct objectives.

First, they want the central bank to hold fewer bonds (especially mortgage bonds), because they believe that the size and composition of the Fed’s portfolio affects how everyone else prices risky assets.2

The Fed bought about $2 trillion in bonds in the first months of the pandemic to stabilize markets as forced sellers liquidated bonds for cash to make payments. By May 2020, the Fed had switched to buying bonds at a more measured pace with the aim of supporting economic recovery, adding another $2.5 trillion until April 2022.

Once the Fed had pivoted from promoting growth to fighting inflation in 2022, it made sense that officials would want to begin unwinding their earlier asset purchases. Whatever stimulus may have made sense before was no longer necessary. Even though the Fed may soon begin lowering interest rates, officials still want to see how far they can shrink the bond portfolio because they want to get back to using a single policy instrument (short rates) to influence financial conditions and the broader economy.

At the same time, Fed officials also want to reduce the supply of reserves in the banking system independent of what happens to the asset side of the balance sheet. This is why they say they want reserves to be “ample” rather than “abundant”.

Lorie Logan explained back in November that the goal is to balance the safe asset needs of banks with other financial businesses. Only banks can hold reserves, which are deposits offered by the Fed and backed by claims on the U.S. government (more or less). If the Fed offers “too many” reserves to banks, the concern is that “the central bank adds to the supply of liquidity for banks but may increase non-banks’ cost of liquidity.” I am not sure I buy this argument, especially now that the Fed has a reverse repo facility that many non-banks can use to store cash safely overnight, but it is the most compelling one that I can find.

Offsetting these two complementary goals is one overarching priority: Fed officials want to make sure they do not inadvertantly deprive the banking system of an essential asset necessary to lubricate the flows of commerce. A balance sheet that is “too big” might be less than ideal, but a balance sheet that is too small creates the risk of payment failures and cash crunches.

The challenge is that nobody knows how many reserves are needed to balance these priorities. “Ample” and “somewhat above” are deliberately vague terms that are supposed to capture this uncertainty. The last time the Fed was shrinking its balance sheet, it was forced to reverse course because it had underestimated the amount of reserves needed to keep the banking system and broader financial system lubcricated. While the Fed has made some important changes since then, there are still reasons to be cautious.

“Ample Reserves” vs. “Enough Reserves in the Right Places”

The Fed tries to estimate the amount of reserves that the banking system needs through surveys. If you ask a representative sample of bankers what their “lowest comfortable level of reserves” is you could theoretically aggregate the answers up to estimate what banks as a whole would require. That number would be too small, however, since most banks say that they prefer to hold substantially more reserves on deposit at the Fed than the “lowest comfortable level”. Adding this all up can provide a rough estimate, but only a rough one.

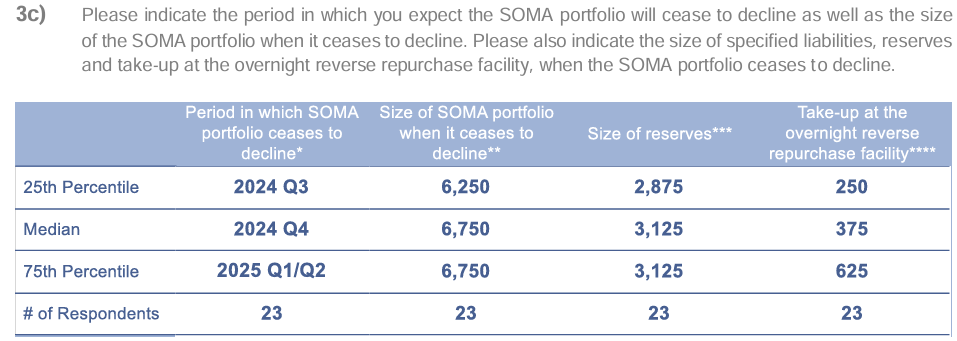

The Fed also asks trading desks what they think is going to happen. In December 2023, most primary dealers thought that the Fed would stop shrinking its balance sheet once reserves hit $3.1 trillion, which they expected will happen sometime in 2024H2-2025H1.

The problem is that these aggregate estimates may overstate the “ampleness” of reserves because they ignore issues of distribution. Stress could show up even when reserves levels seem “ample” if those reserves are concentrated in a few institutions and cannot easily be lent or otherwise transferred to other banks that might need them to make payments or cover deposit outflows. That is what happened in 2019, and it could potentially happen again, even if there are some important differences between now and then.

Lorie Logan’s argument is that this is a reason for the Fed to be ready to start slowing its bond redemptions:

Individual banks can approach scarcity before the system as a whole. In this environment, the system needs to redistribute liquidity from the institutions that happen to have it to those that need it most. The faster our balance sheet shrinks, the faster that redistribution needs to happen…Normalizing the balance sheet more slowly can actually help get to a more efficient balance sheet in the long run by smoothing redistribution and reducing the likelihood that we’d have to stop prematurely.

Quantitative “Tightening” and Rising Reserves

This has not been an issue so far because bank reserves have moved somewhat independently of the Fed’s bond portfolio.