Is This Disinflation "Immaculate" or "Transitory"?

The June CPI and PPI numbers are encouraging, but there are still reasons for caution. The challenge is disentangling the underlying trend from the unwinding of idiosyncratic one-off factors.

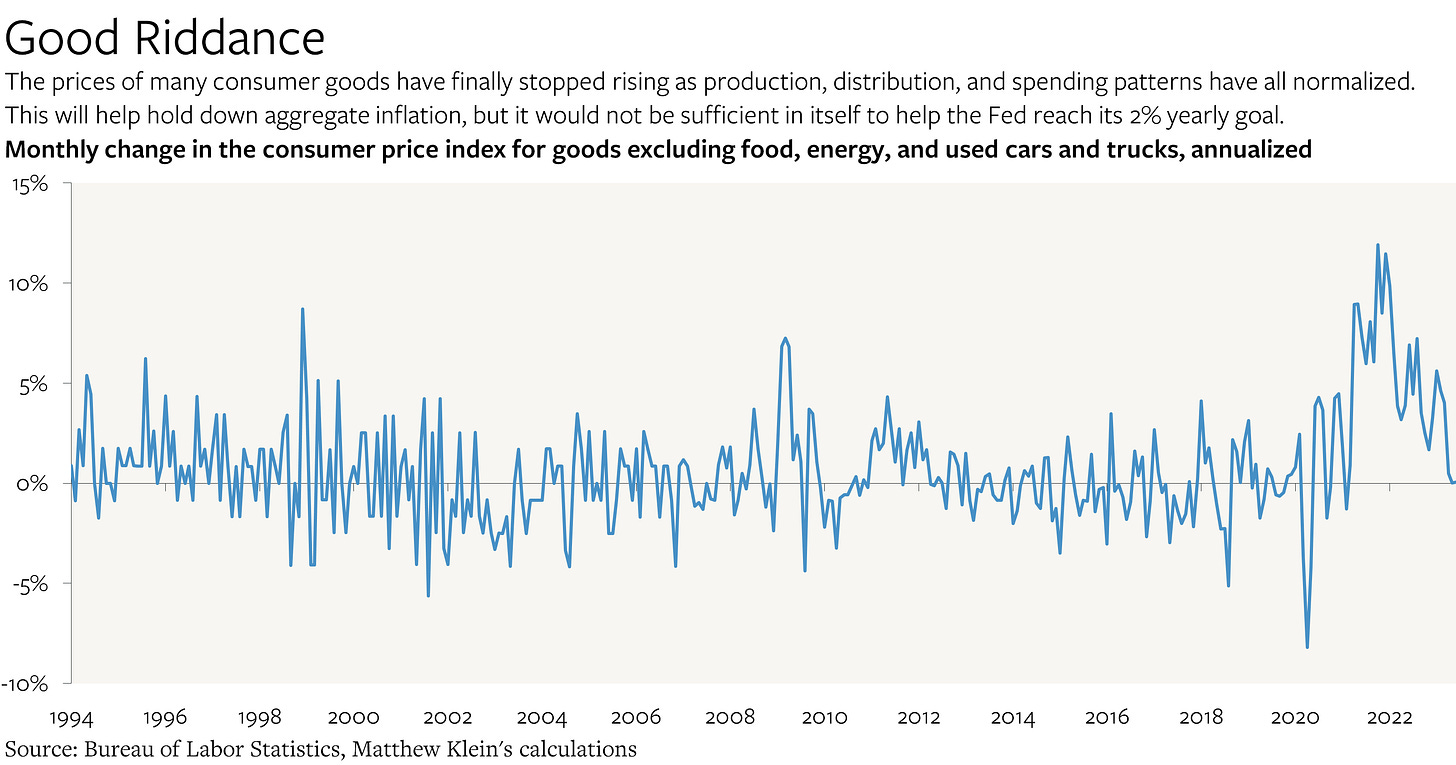

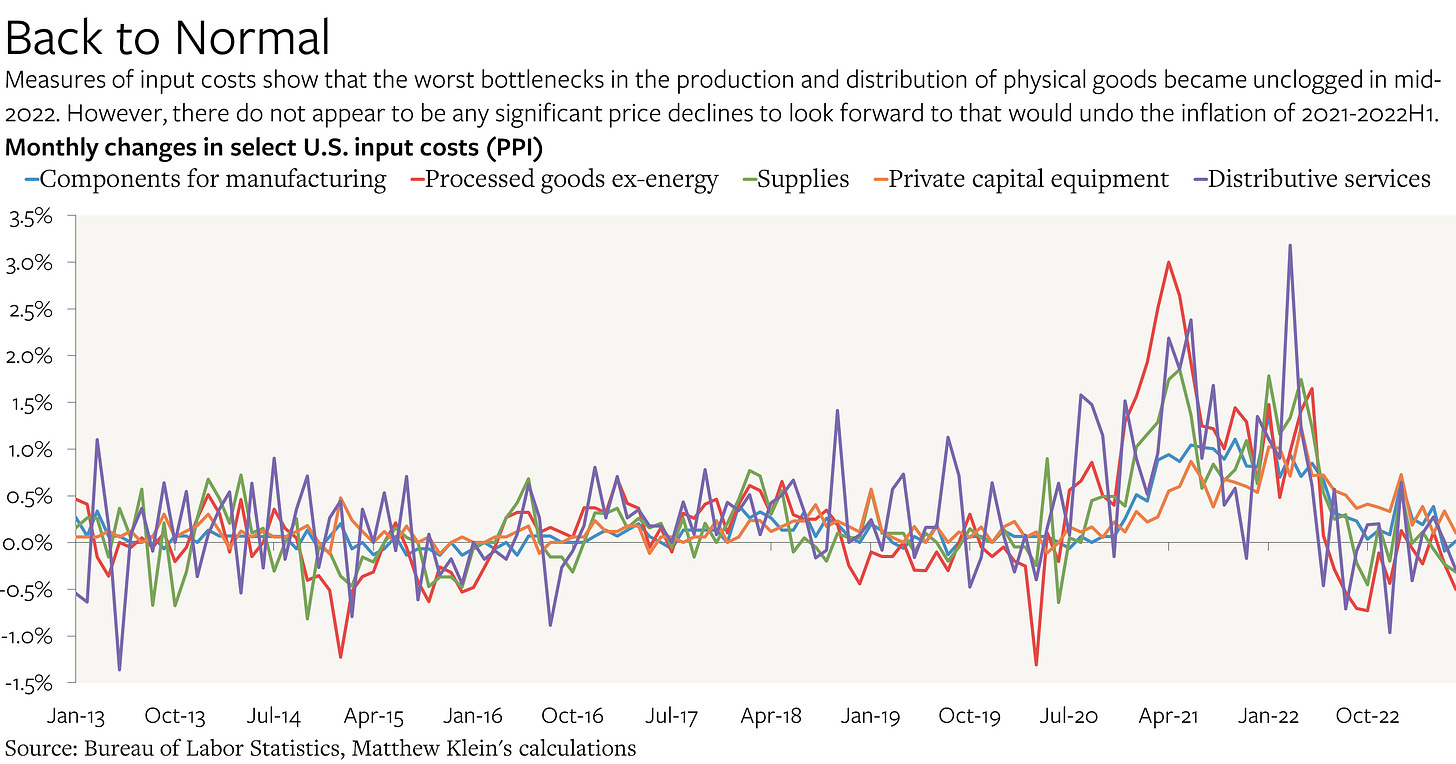

U.S. inflation has slowed sharply since the peak last summer. Monthly price changes as measured in both the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Producer Price Index (PPI)1 have been broadly consistent with the Federal Reserve’s 2% yearly goal for at least four months in a row.

Even better, this has happened without the kind of job losses that many had warned were necessary. In fact, U.S. employment is now higher than what forecasters had been expecting before the pandemic, with particularly large gains in higher-paying full-time jobs. On the surface, it would seem as if the “immaculate disinflation” has been achieved.

Unfortunately, there are reasons to think that the headline numbers are being distorted downwards by the same sorts of temporary factors that made inflation look worse when prices were rising at double-digit annualized rates. While the current benign pricing environment could persist for months, the data on wages (still) suggest that (modest) inflation will return once those temporary factors unwind.

But first: how did we get here?

Getting Over Long Covid-flation

Most of the excessive price increases of 2020-2022H1 were attributable to disruptions associated with the pandemic. People suddenly changed what they wanted to buy—nights on the town and dental checkups were out, kitchen renovations and hand sanitizer were in—at the same time that a highly-contagious respiratory virus was making it extremely difficult for businesses to produce and distribute anything. Businesses that had been optimized to satisfy a particular mix of consumer desires needed time to adapt, which led to shortages. You cannot manufacture exercise equipment out of empty planes and grounded pilots, nor can you simply put furloughed dentists to work in empty movie theaters to churn out N95s or laptops.

Making matters worse, businesses in key sectors such as motor vehicles and energy decided to preemptively cut both current production and future capacity to avoid getting stuck with excess inventories. While those decisions were understandable in the harrowing months of March-April 2020, the consequences for everything from oil refining to car rentals were still being felt years later.

Scarcity was managed through a mix of quantity controls (“please only take one toilet paper roll”), delivery delays (“your bike/couch/washing machine will arrive in four months”), and price increases.

In the first year of the pandemic, unusually rapid price increases in some categories were offset by unusually slow price increases—or even falling prices—elsewhere. Once mass vaccinations made it possible for the economy to reopen, prices spiked in categories that had been depressed, such as airfares, hotels, and clothing. But there was no countervailing decline in the prices of electronics, appliances, cars, or furniture, which meant that the overall inflation rate was much faster.

A one-off surge in prices was a natural consequence of the fact that governments around the world disbursed tens of trillions of dollars to support incomes at a time when workers and businesses were not producing as much goods and services as before. This was the right choice, because the alternative would have been a massive financial crisis. A bump in the overall price level also made it easier for relative prices to repeatedly adjust in response to consumers’ shifting desires.

In principle, this sort of inflation should have gone away on its own as the public health situation normalized, job churn slowed, and businesses’ output finally aligned with what people wanted to buy. And that more or less seems to have happened, although the process was delayed by the most recent Russian invasion of Ukraine, which disrupted the production and distribution of many essential commodities.2

From this perspective, there was never any need to squeeze inflation out of the economy at all. It simply faded away, just as many of us said it would.

Permanent Damage?

But there was always the risk that a prolonged period of excessive inflation—even if it were entirely attributable to temporary issues such as the pandemic and the war—would eventually lead to persistent changes in behavior that might cause the underlying rate of inflation to accelerate. This might not be visible in the headline numbers if it were relatively small compared to the wild swings associated with the virus. It might only be apparent after the post-pandemic disinflation had run its course. The challenge for analysts and policymakers is disentangling the various forces affecting inflation and determining which ones are temporary and which ones are not.

There are good reasons to be sanguine. Survey data have consistently showed that Americans never seriously considered buying things solely because they were trying to get ahead of future price increases.

While market-based measures of forward inflation briefly implied that inflation would temporarily exceed the Fed’s goal, bond prices have been consistent with on-target inflation since last fall.

The main reason to worry is that nominal wages have consistently been rising about 5%-6% a year since last summer. The drop in the share of workers quitting their jobs for better opportunities elsewhere and the declining wage premium for workers switching jobs do not seem to be having an impact (yet).

Since consumer spending tracks wage growth better than anything else, real volumes of goods and services would have to rise about 3-4% a year for the current pace of wage increases to be consistent with 2% inflation. That would certainly be my preference, and there are good reasons to think that productivity might accelerate, but the likelier outcome is that underlying inflation is closer to 4% than 2%.

Squinting at the Bill

The recent action in my favorite inflation indicator—sit-down restaurant meals—reflects the current uncertainty. Dining out is a discretionary purchase that is sensitive to economic conditions, while the input costs are a mix of local rents, taxes, and wages, as well as equipment and groceries. Despite accounting for a small share of the overall CPI, movements in the price index for “full service meals and snacks” tend to track the broader price index remarkably well. The question is how to interpret the recent data.

From one perspective (the dashed light blue line), it looks as if inflation has normalized. But that could be a headfake attributable to the volatility of the data. It would not be the first time that short-term changes in the sit-down restaurant price index were misleading. By contrast, the 6-month moving average of monthly changes (the dashed red line) is remarkably consistent with the data on overall wages.

Regardless of what I want to happen, the experience of the past three years makes me reluctant to conclude that something fundamental has changed after only a few months of somewhat encouraging data. (Remember that the Fed’s preferred measures of underlying inflation have shown almost no progress at all over the past year.) Broad price inflation cannot remain disconnected from nominal income growth by very much over any meaningful time horizon. At this point, the hope is that the current bout of disinflation buys time for wage growth to (somehow) slow down on its own without the need for any active measures to hurt the economy. The alternative does not seem to be priced in.

The CPI is supposed to track the prices seen directly by American consumers on their out-of-pocket expenses. Category weights are based on surveys of what Americans say they buy, and the largest category is housing. The PPI tracks the prices that American businesses charge to their customers. Neither imports nor housing are included. Weights are based on actual production according to the quinquennial Economic Census, and the largest component is healthcare. The CPI tracks healthcare prices based on co-pays and other out-of-pocket charges, while the PPI looks at what providers charge to insurers. Despite these and other differences, the two measures mostly move together, which reflects their common sensitivity to changes in nominal spending power and production.

The normalization of government spending and of interest rates also played a role, but I do not see why the withdrawal of temporary measures imposed during an emergency should be considered economically significant compared to the end of the emergency itself. There has been a notable slowdown in bank lending since the end of last year, but it is not clear how much that matters given the relative unimportance of credit growth in this cycle.

Medical care services has been a persistent drag on inflation for the past year. It’s my understanding that the way this is measured lags significantly. Is there a more accurate way to track what is going on in this space? Or how it might be impacting overall inflation?