Russian War Spending May be Maxed Out

The official budget deficit surged last year, as did off-balance sheet military spending via the banking system and unpaid bills. That might be tough to sustain, especially with lower oil revenues.

Russian military spending and other war-related expenditures surged last year even as oil and gas revenues fell, with the difference covered by a mix of higher taxes on the domestic non-O&G economy, cuts in non-military spending, public borrowing, liquidation of reserve assets, monetization of gold holdings, and a massive credit expansion via the banking system. Yet, even with the Ukrainians squeezed by the reduction of support from the U.S.1, the faster tempo of operations financed by these extraordinary measures failed to generate meaningful breakthroughs on the battlefield.

That has implications for the negotiations currently underway in Abu Dhabi.

Russian officials have repeatedly insisted that they will only end their war on Ukraine if, among other things, they are given territories in Donetsk and Luhansk that they have been unable to conquer. The land in question is filled with defensive fortifications and difficult terrain, protecting the rest of Ukraine from Russian infantry and armor. Having failed (so far) to take it in battle, the Russian strategy over the past 12 months has focused on trying to convince U.S. officials to pressure the Ukrainians into surrendering the territory without a fight. The Russian argument is that their victory is inevitable, and that conceding now would be better than accepting the (far worse) terms of any future peace deal.

It takes heroic levels of squinting to notice meaningful changes in the Institute for the Study of War’s maps of assessed control of terrain between now and last year. The Russians have managed to advance a little bit compared to where they were three years ago, although not very far considering how much effort they have expended. They have proven far more capable of terrorizing Ukrainian civilians than gaining territory.

The latest official data from Russia’s Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) suggest that the Russians may find it difficult to ramp their spending further. In fact, the publicly-available information suggests that they are already responding to constraints by raising taxes even more and planning for spending increases smaller than inflation. Those constraints are being exacerbated by the increasing pressure on oil exports due to tighter sanctions and the seizure of Russian ships, which should limit how hard they can continue to fight.

And if the Russians cannot increase their efforts from current levels, they will find it difficult to make much further progress—as long as Ukraine retains the support of its democratic allies. Rather than pushing the Ukrainians to accept a potentially unsatisfactory deal, the allies’ goal should be to force the Russians to realize that it is futile for them to keep fighting. The rest of this note covers the following points:

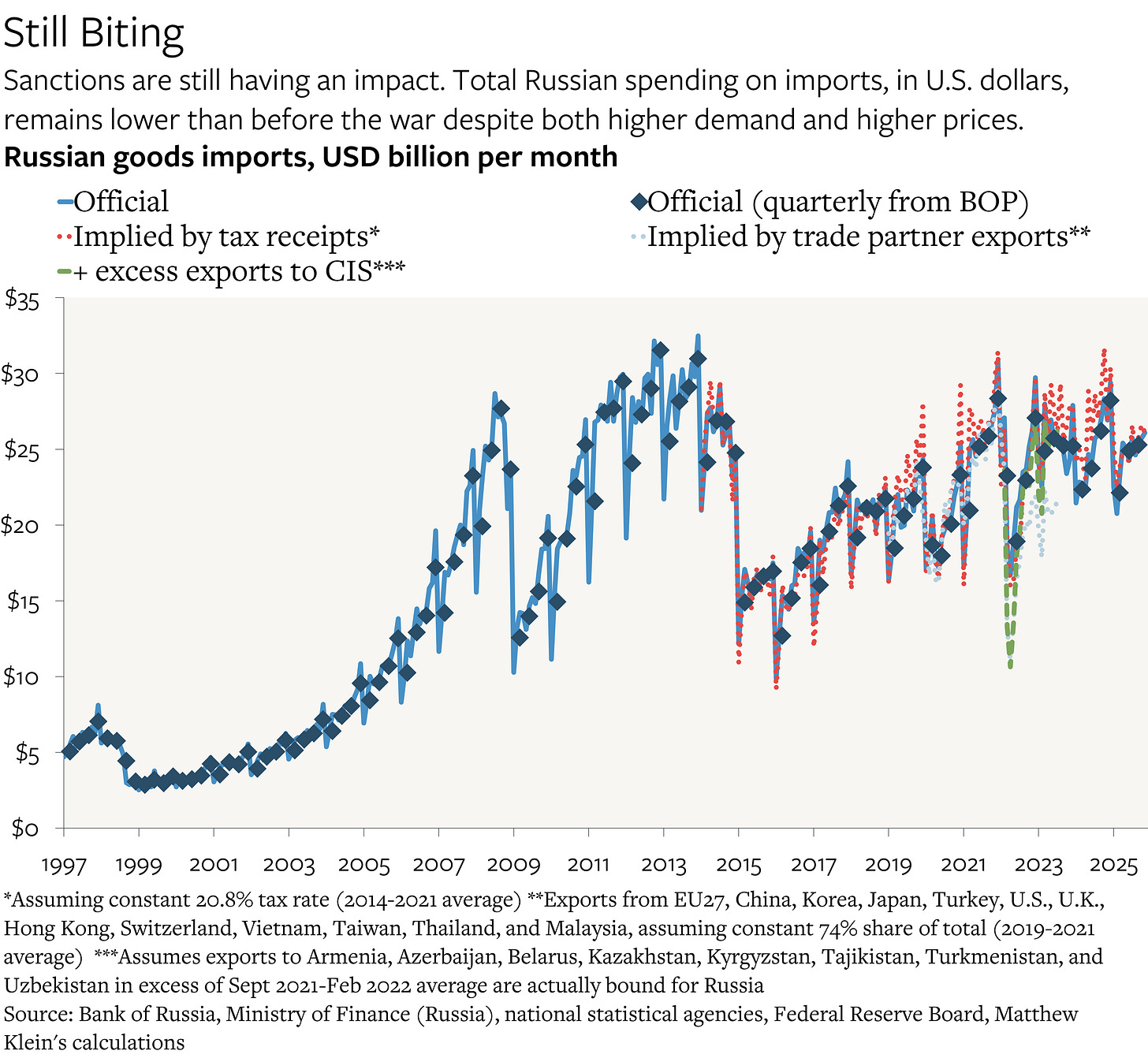

Russian imports of critical goods remains constrained by sanctions, but it is less clear how much, if at all, the drop in oil and gas revenues is limiting imports

Russia’s official numbers show that spending by both the federal government and the “constituent entities” rose sharply in both ruble and U.S. dollar terms, mostly thanks to a rise in the budget deficit, while the “Pension fund and social insurance fund of the Russian Federation” has also moved into a sharp deficit

The “National Welfare Fund” has been selling gold for rubles to provide additional support to the military

The Russian banking sector has sharply increased its lending to businesses associated with the war effort even as the government’s uncollected bills from the private sector have soared

Sanctions Are Still Constraining Russian Imports

The Russian military is extremely dependent on imported parts and components, and even the producers who manufacture weapons in Russia rely on imported capital equipment. The allies were able to inflict significant damage on Russia’s ability to fight via financial sanctions and export controls, which severely limited the Russians’ ability to import critical military goods.

The impact of those restrictions has weakened somewhat over time, both because European producers have been exporting to cut-outs in Central Asia and the Middle East, and because Chinese producers have decided to push the limits of the enforcement regime, but even so, the Russians are still unable to import as much as they would like from the rest of the world. After accounting for inflation and Russia-specific markups, the real value of imports, particularly of strategic goods, is substantially lower than implied by looking at the dollars spent.

Economists at the Bank of Finland estimate that “the median price change in exports to Russia was 75% for sanctioned goods and 0.2% for non-sanctioned goods” between 2021 and 2024. And the amount of dollars spent on goods imports is still (slightly) lower than in the pre-war period, which is why (different) economists at the Bank of Finland estimate that real imports of sanctioned goods fell by 27% by the end of 2023, which imposed large and persistent costs on Russian businesses involved in the military and high-tech sectors.2

Limits on Russia’s exports, particularly its exports of crude oil, refined petroleum products, and natural gas, have had less of an effect. The biggest reason, as I have warned for years, is that Russians earn so much more from their exports, including their non-energy exports, relative to what they spend on imports that it would be difficult to constrain their international purchasing power solely by suppressing their revenues from fossil fuels. The combination of lower oil prices and the oil price cap has done relatively little to dent Russia’s overall export earnings from selling goods to the rest of the world, which were $420 billion in 2019, $425 billion in 2023, $434 billion in 2024, and about $413 billion in 2025.

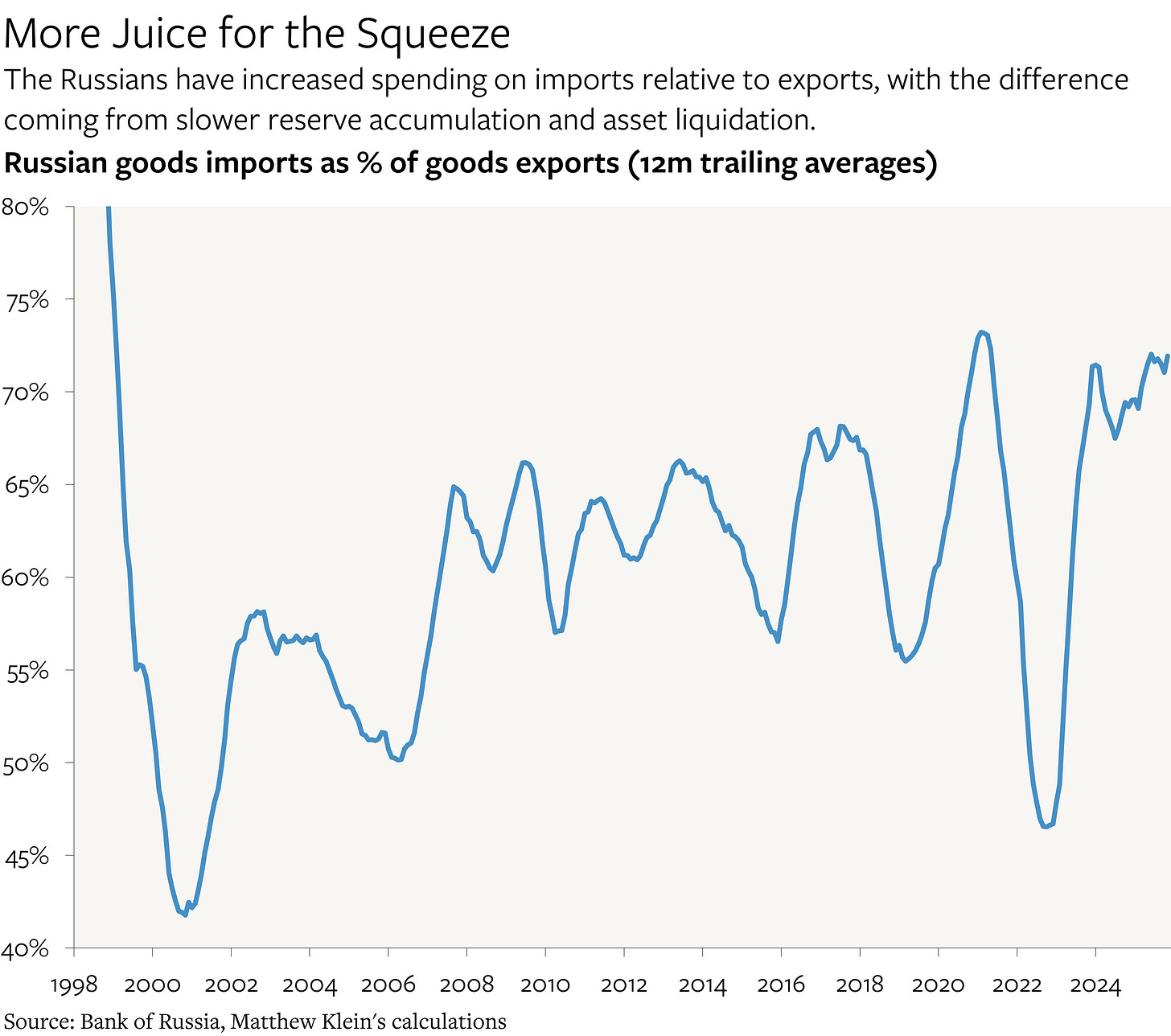

And to the extent that goods export revenues are slightly lower, Russian importers have offset the impact by simply spending slightly more on imports, relative to exports, than they did in the pre-war period (about 72% of goods exports in 2025 vs. 63% in 2014-2021).

There is plenty of room for the allies to tighten their export controls to limit transshipment through third countries. That should have been done years ago, but it would also be helpful to do it now, especially if the Russians continue to be intransigent about territory or other issues during the peace talks.

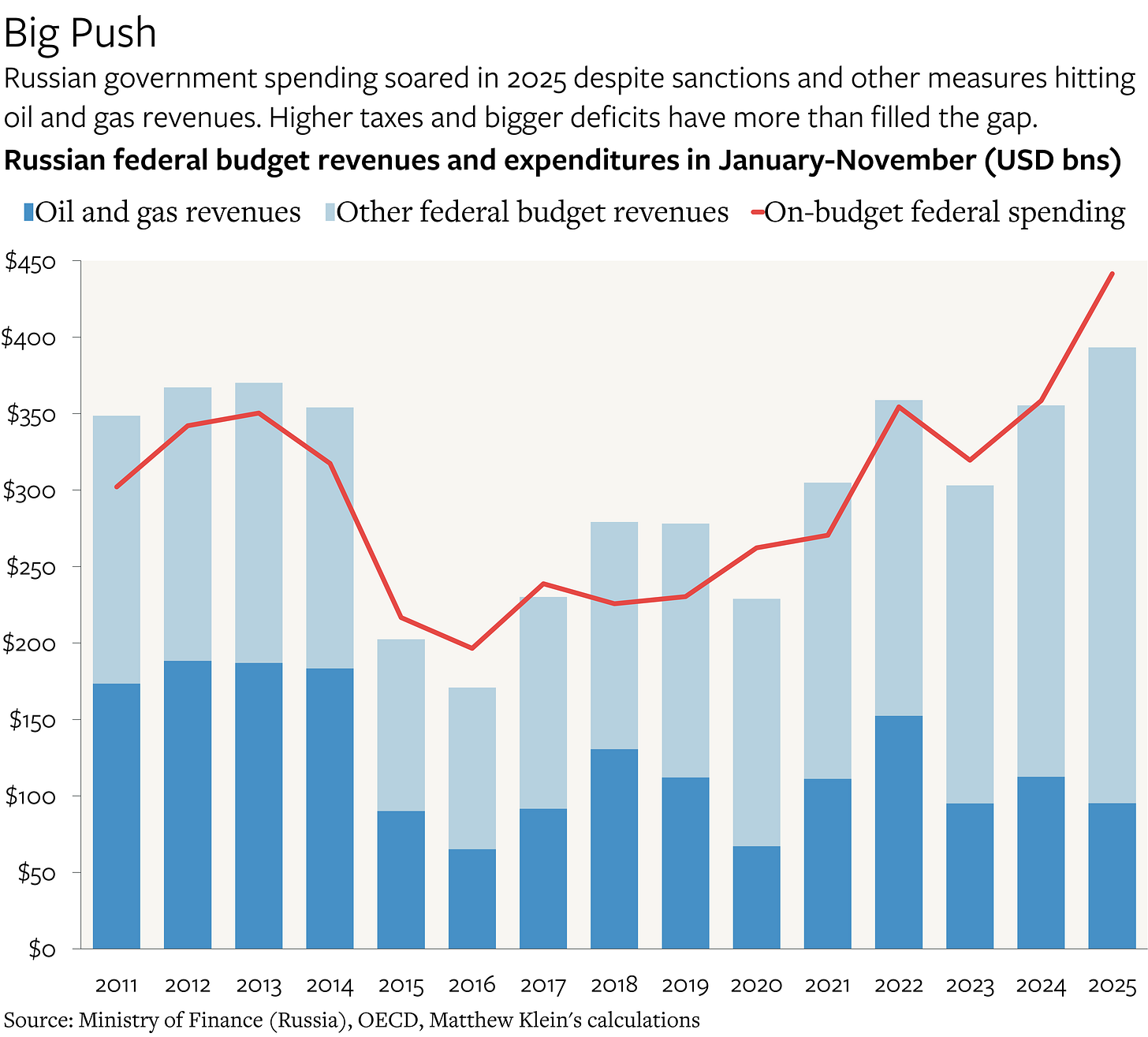

The Russian Government’s Spending Spree

According to the Russian ministry of finance, federal government spending—excluding transfers to “constituent entities” of the federation—in the 12 months ending in November 2025 was 15.3% higher (₽5.3 trillion) than in the 12 months ending in November 2024 in ruble terms. By contrast, revenues were up only 3.1% (₽1.1 trillion). Oil and gas revenues fell 19.4% (₽2.1 trillion), while tax revenues from import duties were down 11%. Taxes on the domestic non-oil and gas economy jumped by 30% (₽3.7 trillion).

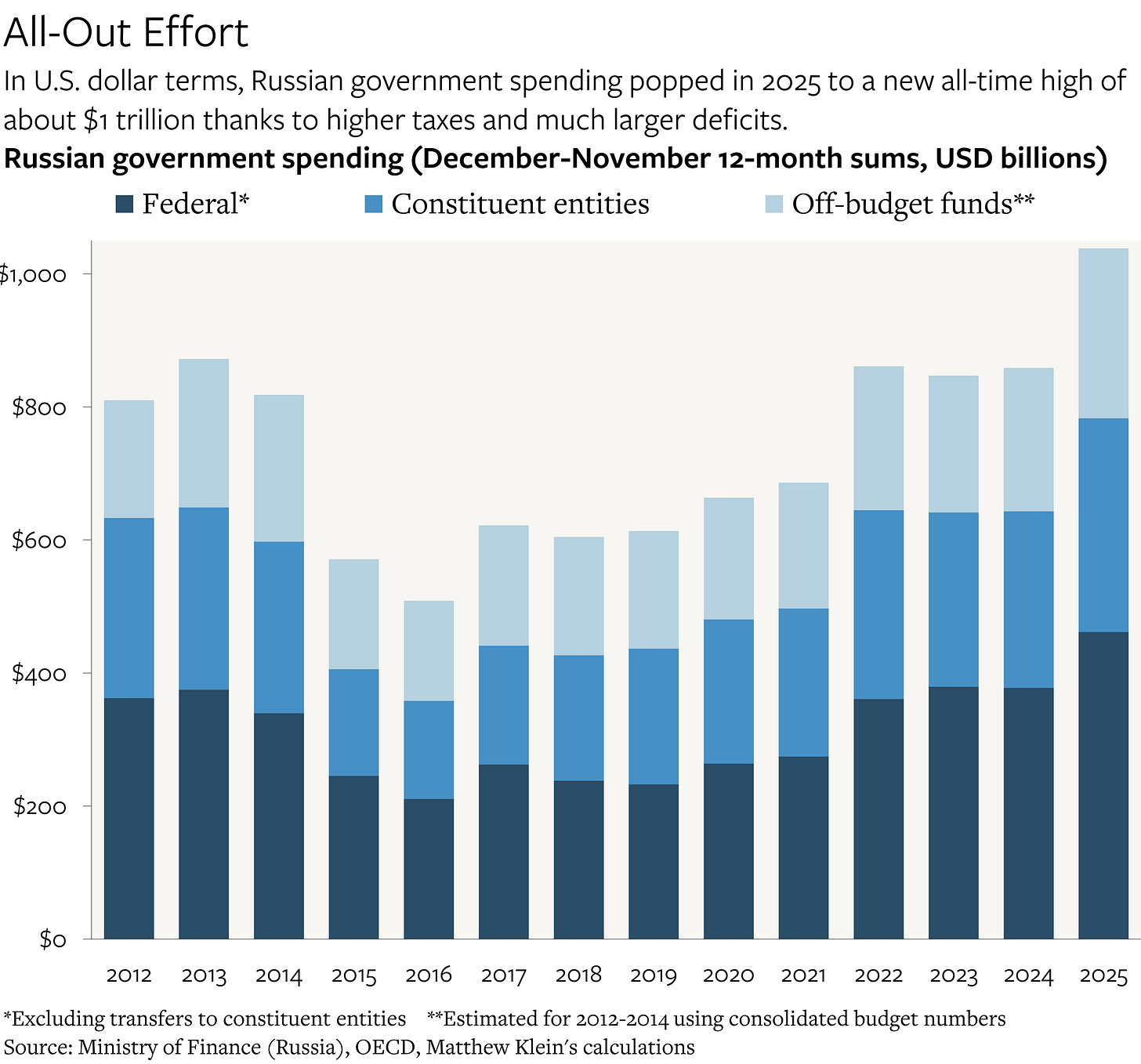

For Russia’s “constituent entities”, which are responsible for substantial amounts of total spending, including for “national security and law enforcement”, spending was up 13.8% (₽3.4 trillion), while revenues excluding federal transfers were up only 6.3% (₽1.3 trillion) and transfers were up 8.1% (₽320 billion). The “off-budget funds” saw spending rise by 9.7% (₽1.9 trillion), mostly because the “pension and social insurance fund of the Russian Federation” saw expenses rise by about ₽1.4 trillion over the previous year. Revenues rose by 4.7% overall (₽950 billion), with revenues for the pension and social insurance fund up only 2.4%.

The pace of spending growth (in rubles) for the federal government, constituent entities, and “off-budget funds” was not much different from the year before, but revenue growth was much slower for all three (~5% vs ~20%). The result is that the combined budget deficit of the federation and constituent entities soared from about ₽2.8 trillion (4.7% of net spending) in December 2023-November 2024 to ₽9.1 trillion (13.3% of spending) in the 12 months ending in November 2025, while the balance between revenues and spending of the off-budget funds swung from +₽264 billion to negative ₽700 billion, for a total increase in the consolidated deficit of about ₽7.3 trillion.

Even with massive increases in value-added taxes, excise taxes, income taxes, and social insurance taxes, more than 80% of the increase in Russian federal spending over the past 12 months was financed by an increase in the deficit and more than 70% of the increase in spending by the “pension and social insurance fund of the Russian fund” was financed by an increase in the deficit. Across the consolidated budget, incremental deficit increases financed about two-thirds of the overall spending increase (in rubles).

Relative to the Russian economy, which is more than ₽200 trillion, these numbers are still relatively small, and Russian government debt is extraordinarily low relative to national income, especially when viewed in comparison to other countries. Nevertheless, Russian officials seem to believe that the additional rubles pumped into the economy via these budget deficits are unwelcome, which is why they are planning for slower nominal spending growth going forward, including no additional spending on the military and national security in 2026 compared to 2025 (in rubles).

It is perhaps more informative to consider the evolution of the budget in U.S. dollars, which helps adjust for changes in Russian inflation and for changes in the international prices of goods imported for the war effort. According to Russia’s official statistics, consumer prices rose by 7.4% in 2023, by 9.5% in 2024, and by 5.6% in 2025, which implies that real government spending rose much more in 2025 than in 2024. Somewhat counterintuitively, the ruble also appreciated against the dollar even as the price of Brent crude oil fell and as the discount of Urals crude to Brent rose.

The result is that Russian federal government spending, in USD, was 23% higher in January-November 2025 than in January-November 2024, which itself was essentially unchanged vs. January-November 2022. Energy revenues were lower in 2025 than in 2024, but perhaps not as low as one might have expected given the tightening in sanctions, the drop in oil prices, and Ukrainian strikes on Russian refineries. (Monthly spending numbers are often lumpy, with big spikes each December, but the picture looks the same when comparing 12 month sums from December-November.)

Similarly, spending by Russia’s constituent entities was up 21% in 2025 vs. 2024 and 2023 (in USD), while spending by the pension and social insurance fund was up 17%, after having been roughly flat in USD terms throughout 2022-2024. The official numbers imply that combined spending across all the layers of government was about 20% higher (in USD) in 2025 than in prior years, which is a meaningful increase relative to both the start of the war and the prior peak before the 2015-2016 oil price crash.