The Latest Argentina Bailout will (Probably) Fail

The U.S. Treasury's interventions on behalf of Argentina are unlikely to succeed as long as the country's fiscal probity fails to offset monetary laxity and an overvalued exchange rate.

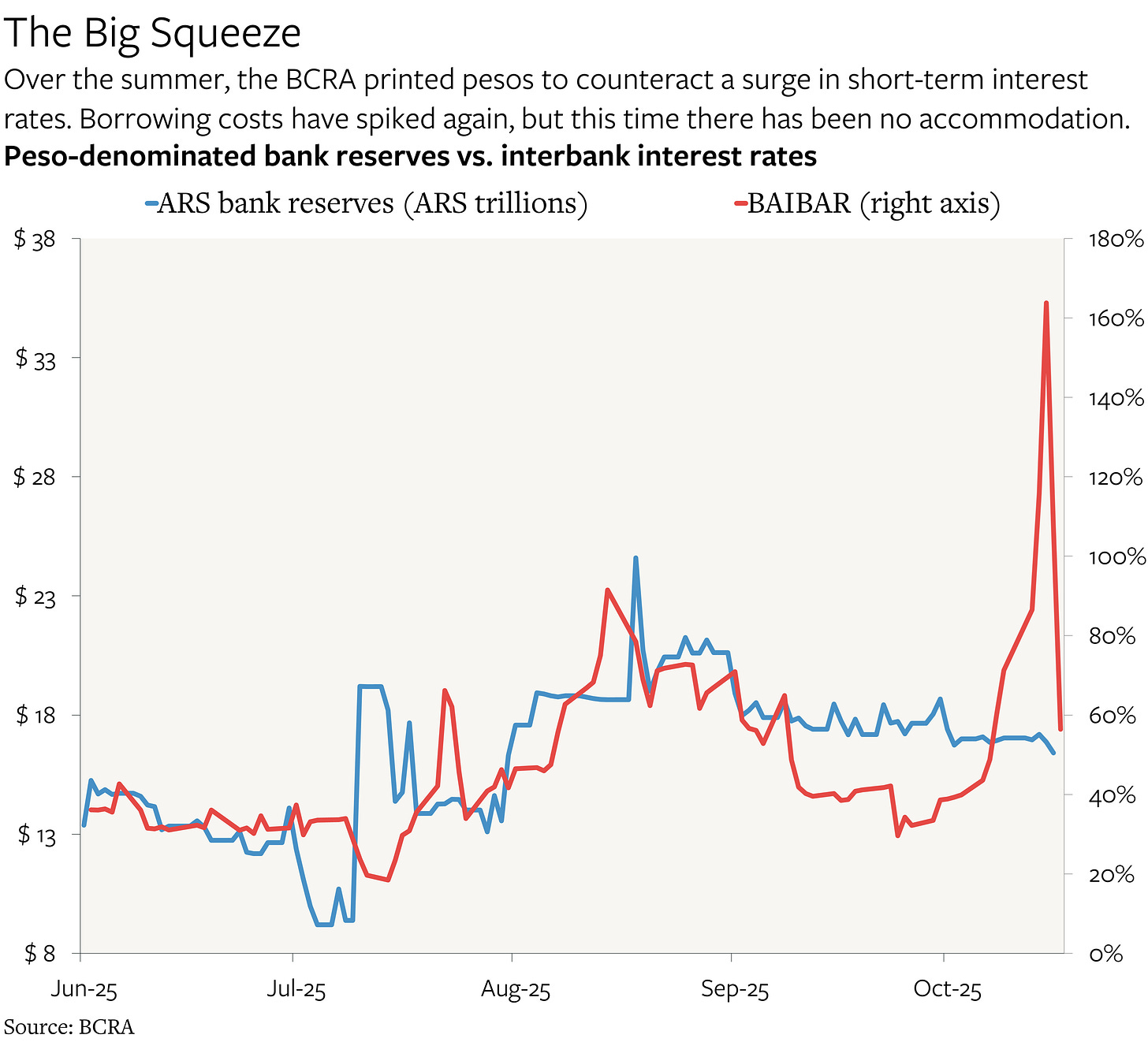

Argentina is in trouble. The short-term interbank interest rate benchmark (BAIBAR) had spiked to 165% last Wednesday, up from 40% at the beginning of October. Unlike over the summer—the last time borrowing costs spiked—Argentina’s central bank (the BCRA) did not relieve the pressure by printing peso bank reserves.

BCRA officials probably felt constrained by the ongoing pressure on the peso’s international exchange rate. BAIBAR has come down substantially since then as U.S. government officials have decided to increase their support for the Argentine peso by buying the currency outright, but the situation remains tenuous.

What happens next?

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent claimed on October 17 that “we have the capacity to act with flexibility and with force to stabilize Argentina”. The BCRA has also announced the agreement of an official swapline “with the United States Department of the Treasury for an amount of up to USD 20 billion”, although the terms are not public and there is no corresponding announcement on the U.S. Treasury’s website. While there is no hard limit on how many U.S. dollars the government can create, it is not clear what amount of USD, if any, would be sufficient to get Argentina out of its current predicament—to say nothing of whether that would be a good use of the money.

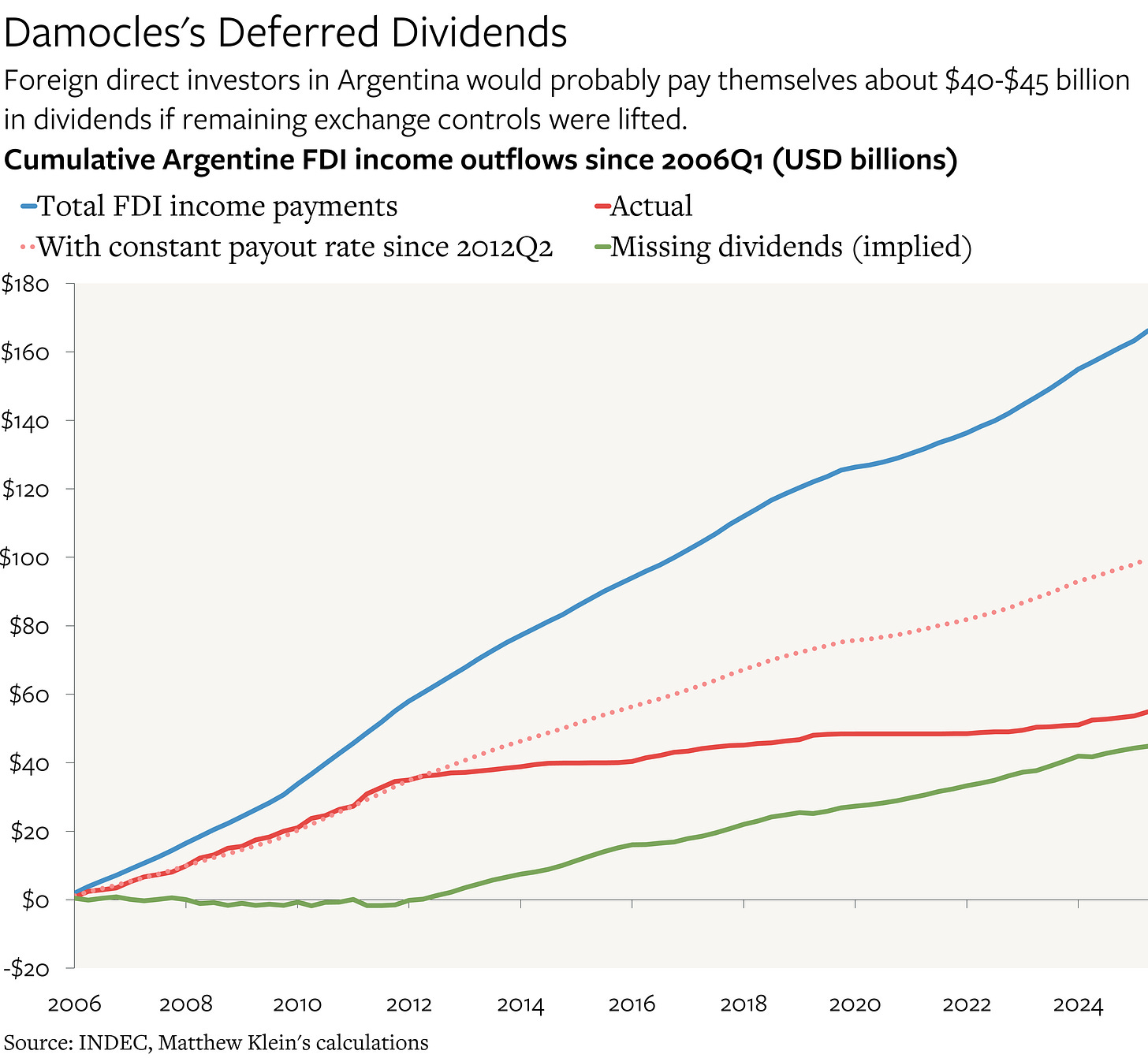

As a first approximation, there are about $90 billion of private sector Argentine bank deposits denominated in pesos that have yet to be converted into hard currency or pulled out of the banking system entirely, plus around $43 billion of unpaid dividends owed to foreign direct investors.1 Argentine officials are well aware of this latent pressure on the currency, which explains why they still refuse to let companies pay dividends out of retained earnings generated before this year.

Then there are the ~$137 billion in Argentina’s net external debts, most of which are denominated in USD, with their associated interest and principal obligations.2 So even if the U.S. donated $250 billion outright—equivalent to more than 1/3 of Argentina’s national income—it still might not be enough to satisfy Argentines’ desire to replace pesos with USD at current exchange rates. From this perspective, temporarily lending $20 billion does not seem likely to accomplish much beyond bailing out some of Argentina’s short-term foreign creditors. (The Argentine government has to pay about $18 billion in interest and principal to foreigners over the next 12 months.)

How did this happen? While I would encourage anyone interested to read my previous note on the subject, it is worth digging into how Javier Milei’s government undermined its stabilization efforts almost from the beginning. This note also tries to estimate the size of the U.S. Treasury’s intervention thus far.

Milei’s Mistake: Expansionary Austerity

Argentina’s budget cuts have been substantial. But they have not been nearly big enough to fix the country’s inflation problem, nor were they sufficient to stabilize the peso. Ironically, Milei’s problem was that he succeeded where many others have failed, boosting growth while slashing government spending. While this rare case of “expansionary austerity” bolstered his political support, at least at first, it also exacerbated the country’s balance of payments stresses.

The problem is that the Milei government more than offset the impact of fiscal tightening with a credit boom to the private sector. The U.S. dollar value of Argentine banks’ claims on individuals and businesses tripled between the end of 2023 and March 2025. The extra credit was worth about $56 billion, or almost 10% of Argentina’s national income.

Put another way, the consolidated government budget balance shifted from a deficit of 8.4 trillion pesos in January-December 2023 to a surplus of 1.8 trillion pesos in January-December 2024, which deprived the private sector of about 10.2 trillion pesos of purchasing power. But Argentina’s domestic financial system printed 45 trillion pesos (worth $39 billion at the time) of new ARS-denominated private sector credit in 2024, plus $8 billion of net new FX credit.