What Should the U.S. Try to Achieve in Argentina?

Discouraging underconsumption abroad is normally a good use of American financial resources. But still.

It was only a few months ago that visiting Argentine officials were being feted at the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Spring Meetings in D.C. I got to see this firsthand when Santiago Bausili, the head of Argentina’s central bank (BCRA), presented his achievements to a fawning audience, as well as when Federico Sturzenegger, Argentina’s Minister of Deregulation and State Transformation, was cracking jokes on stage with IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva. At the time, I was among those impressed by their presentations, and was preparing to write a note about how Javier Milei’s government had made tremendous progress, even if there was still a lot of work to do.

Fortunately for me, I never got around to publishing what I was working on. In the months since, Argentina’s longstanding vulnerabilities to capital flight and inflation have reasserted themselves with a vengeance. Now the U.S. Treasury is preparing to commit tens of billions of dollars to Argentina through some combination of lending dollars to the BCRA, buying dollar-denominated Argentine government bonds, and (maybe) even buying Argentine peso assets. The IMF is apparently “coordinating support”, which could involve loans from the ~$175 billion of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) held by the Treasury. According to Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, the goal is to give Argentina “the tools to defeat speculators, including those who seek to destabilize Argentina’s markets for political objectives.”

At one level, this is incredibly stupid, because the Argentine government will almost certainly fail to repay the Treasury without doing something rash.1 At another level, however, I think that there is a germ of a good idea in Bessent’s proposal. The U.S. government should be more willing to take credit risk for the sake of mitigating balance of payments crises. The question is whether Argentina is the best case for doing this.

Lose Money Now, or Later

Ever since the 1920s, the biggest problem afflicting the international monetary and financial system is that the costs of excessive debt have been borne disproportionately by those who borrowed too much, while those who lent too carelessly were relatively shielded from any burden of adjustment. Aside from being unfair, this one-sided approach is guaranteed to retard global growth.

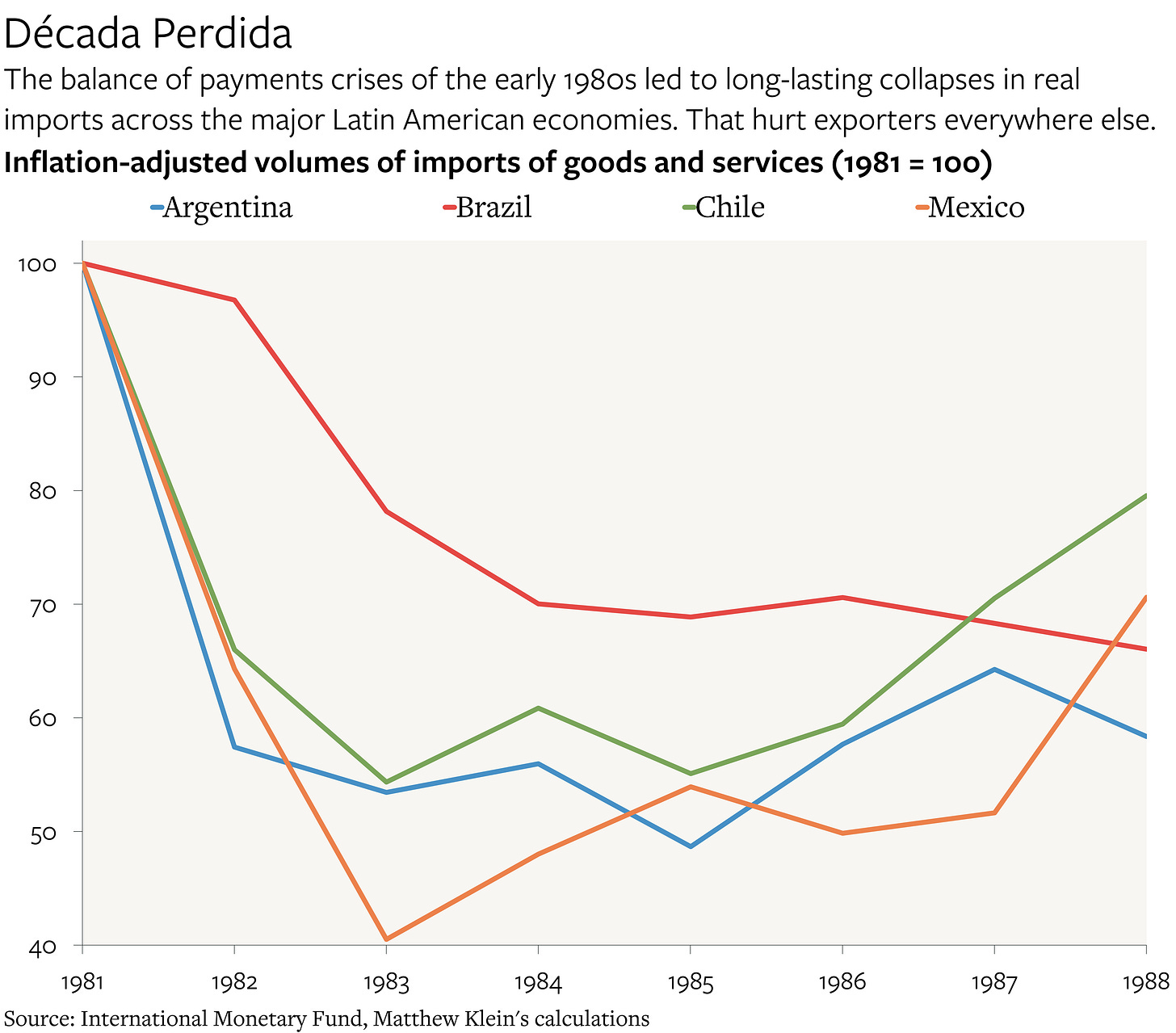

The immediate problem is that the people who were “living beyond their means” are forced to cut their spending—without any commensurate increase in spending by those who have the financial wherewithal to do so. The result is a drop in global demand that makes it harder for otherwise viable businesses to survive, no matter where they are based. That was what happened in the early 1980s, for example, when real import volumes plunged by as much as 60% in what were then called the “less developed countries” as they lost access to foreign financing. That corresponded to lost sales and company failures in the rest of the world. Creditors may have benefited from policy choices that prioritized their interests, but most people in the creditors’ home countries did not.

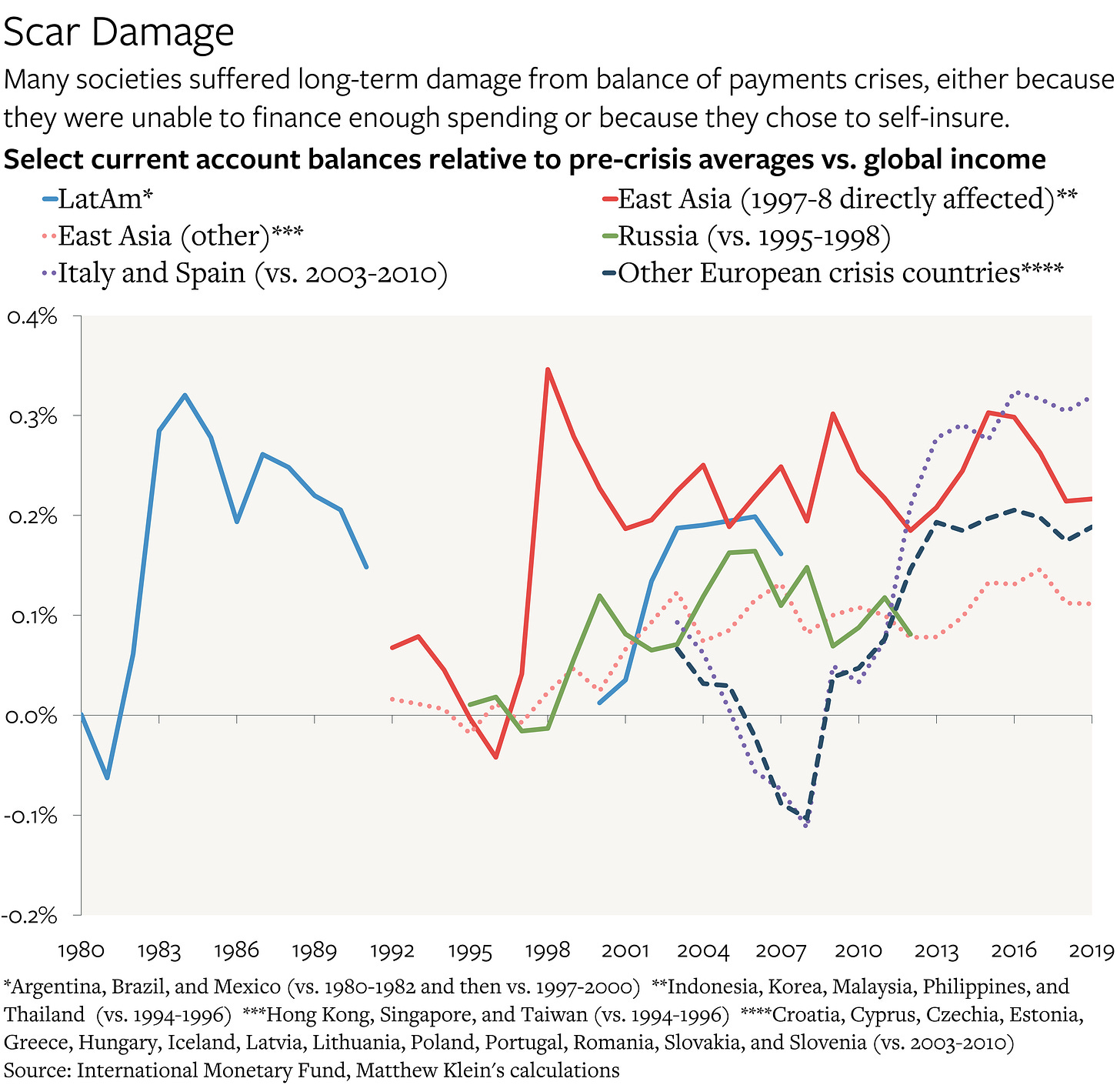

Even worse than the short-term effect is what happens when people learn that the only way to avoid painful sudden stops is to live perpetually below their means, spending less than they could on things that they want so that they can instead hoard reserves. That was what happened after the emerging market crises of 1997-8, and again after the euro crisis. The longer-term costs are persistent underconsumption and underinvestment, particularly in places that have experienced crises. The flip side is that many of the places that would benefit the most from additional capital investment are either paying punitive costs for financing, or are effectively transferring their own spending power to places that do not need it.

This has costs beyond the immediate economic ones, just as Keynes and the other founders of the IMF would have anticipated. Orbán’s authoritarian takeover of Hungary—and his tilt to China and Russia—was facilitated by the reluctance of the European Central Bank (ECB) and others to provide enough support during the financial crisis. He learned that lesson well enough to prevent being squeezed in the years since.

Perhaps even more consequential is what (may have) happened in Türkiye. I am far from an expert on Turkish politics, but one argument I have heard from people who are experts is that Erdoğan’s political transition can be at least partly explained by his supposed belief that Americans and Europeans have repeatedly let him down at crucial moments.2 The two most important episodes in this narrative are the French efforts to block Türkiye’s accession to the European Union in 2004 and the U.S. removal of its Patriot missile defense system from Türkiye during the Syrian civil war.

I do not know how much Erdoğan’s perceptions of these events actually explain his behavior, if at all, but if they are as significant as some suggest, then the decisions to exclude Türkiye from the Federal Reserve’s emergency lending in 20083 and again in 2020 should also be viewed as having contributed to the country’s authoritarian turn and its tilt towards Russia. From this perspective, it is notable that, unlike Hungary, Türkiye remains in a relatively fragile balance of payments position, although things have improved since 2023.

Preventing these sorts of outcomes is literally what the IMF is for, although it has sadly fallen short throughout its history. The good news is that the U.S. has both the ability and the self-interest to do much of the job by itself, should officials choose to pursue the path of enlightened self-interest. As I put it when asked for my thoughts on this question by members of the previous U.S. administration:

The U.S. government could build on its role as an intermediary of these destructive cross-border flows by massively expanding its provision of development finance and balance of payments support to the rest of the world. The catch is that the U.S. government would have to be willing to endure substantial losses on this international investment portfolio…There might be plenty of [market-based and official] financing going to poor places, but not nearly enough to sustainably raise living standards and protect against crises. Complaints about low yields in the rich countries make it clear that the constraint has been a lack of credible places to invest, rather than a lack of financing.

If even more money is going to go out the door, it will necessarily be going to borrowers who are even less capable of paying it back at market rates of return. So if the U.S. government were committed to meeting financing volume targets that were determined by macroeconomic objectives and development goals—to say nothing of strategic concerns—policymakers would have to be willing to incur some sort of fiscal cost.

From this perspective, there is nothing inherently wrong with risking U.S. taxpayer money to help a foreign country suffering from a balance of payments crunch. But there are good reasons to think that Argentina today may not be the best place to start, even if the Milei team has accomplished much in a short time.

Why is Argentina in this Position?

While corruption scandals and a strong result by the opposition in the Buenos Aires provincial election ahead of the upcoming midterms may be the proximate causes of Argentina’s most recent troubles, the country’s basic problem is that the people who live there do not want to hold their wealth in Argentine assets—and everyone else is only willing to hold Argentine assets when their risk tolerances (and global commodity prices) are unusually high. A society with the industrial mix of Australia and New Zealand cannot afford the politics and institutions of Türkiye.

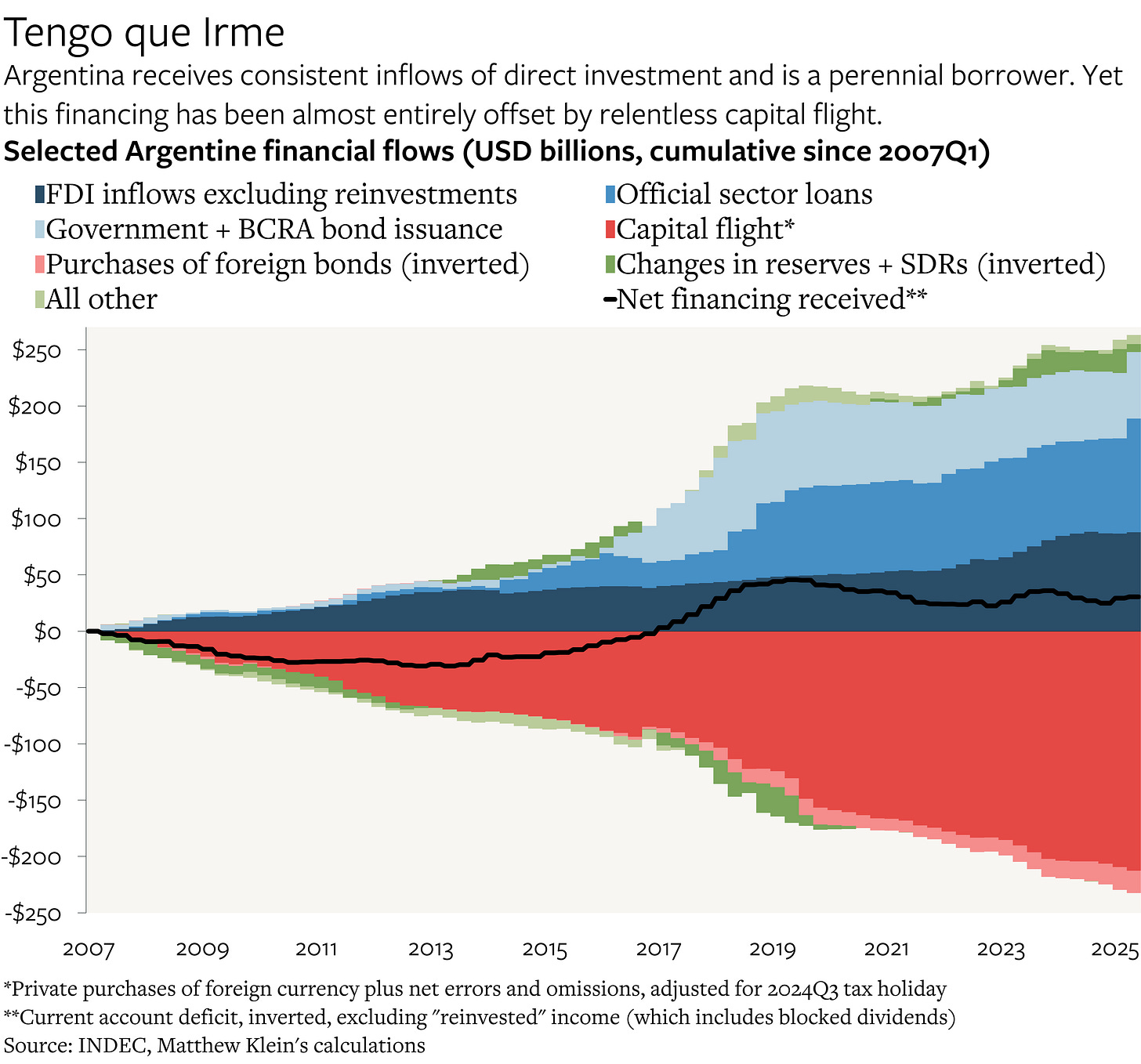

In the nearly two decades since Argentina repaid its last IMF loans in 2006, Argentines have spent more than $200 billion accumulating foreign currency. Over the same period, total inflows of cash to the Argentine government and the BCRA were worth only $160 billion.

Despite persistent trade surpluses, the Argentine economy is often short of hard currency because Argentines prefer to hold hundreds of billions of dollars of cash, stocks, and real estate outside their domestic financial system. Argentines are (rightly) afraid of inflation, devaluation, and expropriation, but the irony is that they hedge these risks so aggressively that they generate precisely the outcomes they wish to avoid.