Time Is Only on the Russians' Side If We Give It to Them

The Putin regime's eagerness for a quick deal is itself indicative of the country's tenuous position.

It has been three years since the Russians tried to conquer to Ukraine. Since then, almost 1 million Russians have been killed or wounded, while another 1 million have emigrated.1

And for what? The Ukrainian government is still committed to joining the European Union. Most of the Ukrainian territory that Russia has “annexed” remains under the control of the government in Kyiv. Russia is now more “encircled” by NATO than ever thanks to Finland and Sweden joining the alliance, while the Ukrainians are far more hostile to Russia—and better-armed—than they were before the invasion. With the notable exception of Russia losing control of some of its own territory to Ukrainian forces, the front lines have barely budged in over a year. The Russians’ “preventative” war has caused enormous suffering but has failed to bolster Russia’s security buffer in any way.

Yet the Russians now have reason to hope that their agents of influence2 in the United States may give them via “negotiations” what they could never hope to achieve on the battlefield: relief from sanctions, international legitimacy, and a prostrate Ukraine that can be conquered at leisure.

While it may not be the correct explanation, the most charitable interpretation is that American decisionmakers sincerely believe that the Ukrainians are doomed to lose eventually, and that there is therefore little point in postponing what they believe to be an inevitability. That assessment seems to be based on the meaningless observation that Russia is a larger country than Ukraine, as well as the erroneous claim that the Russians are not paying much of a price to sustain their aggression.

But that gets things backwards. In reality, the combined (potential) capabilities of Ukraine and its supporters dwarf those of Russia, while Russian society has gone through increasing contortions to continue the war. While sanctions alone have been insufficient to persuade the Putin regime to sue for peace, they have nevertheless been a meaningful constraint creating cumulative and worsening costs for Russian society. The allies could—and should—continue to apply pressure at minimal cost themselves. And if they shifted towards more of a war footing, they could overwhelm Russia’s modest resources.

Russia Is Economically Puny Compared to the Allies

Russia officially has a population of almost 150 million3 and a land area almost as great as the U.S. and Canada put together. It is also a significant producer and exporter of critical commodities from wheat to uranium. But it is an economic minnow when it comes to the production of manufactured goods and high-value services. The notion that a deal with Russia is necessary or advantageous is risible.

According to the International Monetary Fund’s database on economic size adjused for “purchasing power parity”, Russia’s GDP in 2024 was more than ten times as large as Ukraine’s. But when compared against Ukraine’s major supporters, the Russians (and their Belarussian allies) were vastly outmatched.

This metric is supposed to adjust for differences in local prices and wages. Comparing GDP in dollars at current exchange rates implies a much larger gap, which might be more relevant when it comes to the ability to secure internationally-traded manufactured goods and inputs.

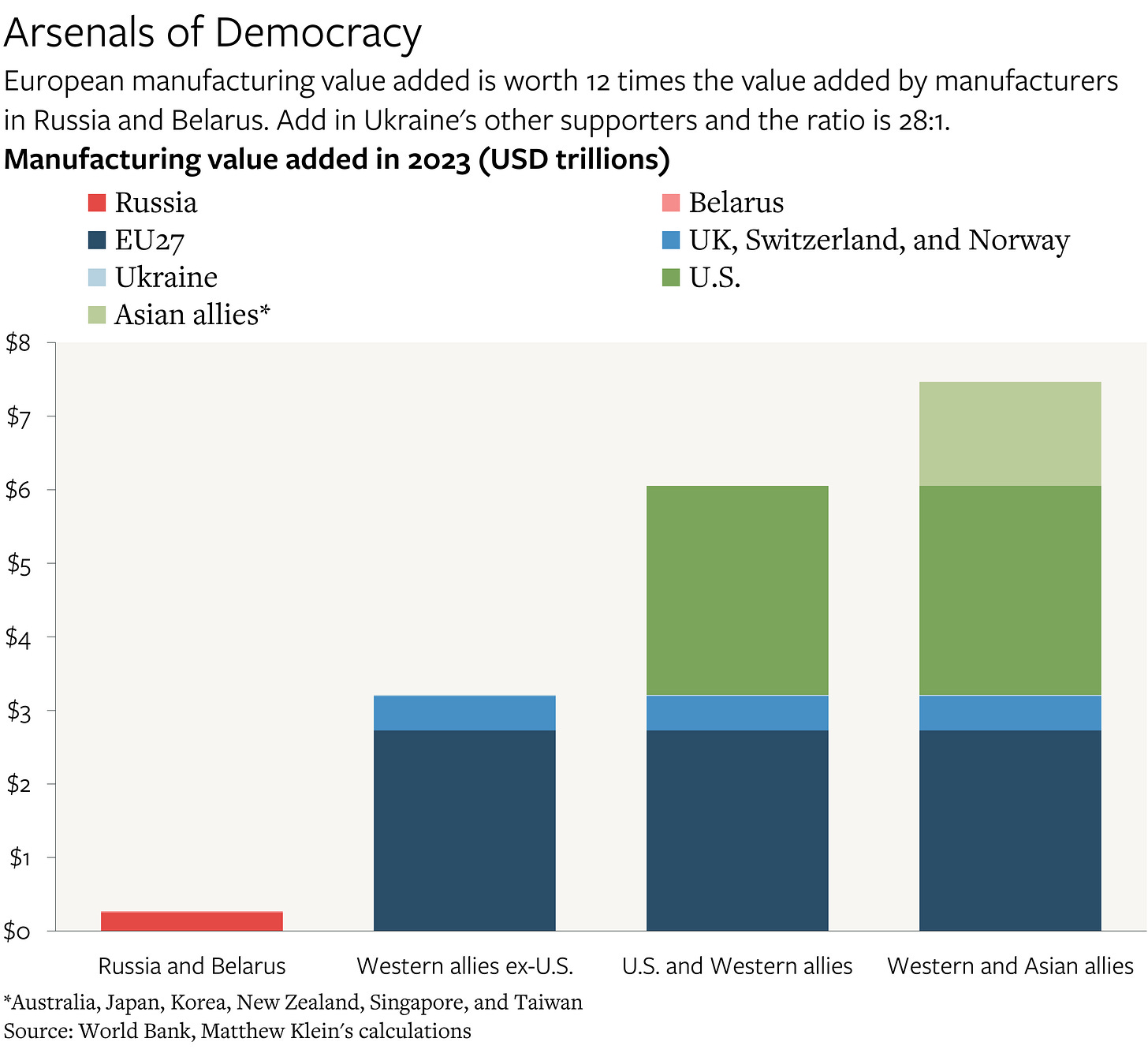

Speaking of which, the World Bank’s data on manufacturing value-added implies that the Russians are far more outclassed than implied by a straight GDP comparison. As of 2023, the democracies ostensibly had a production advantage of roughly 28:1. Even if that number grossly overstates the battlefield implications for various reasons such as exchange rate effects and industry composition—we do not yet fight wars with weight loss drugs or extreme ultraviolet lithography machines—it is nevertheless indicative of the chasm in industrial and technological capabilities.

The Russians are also outmatched even according to old-fashioned metrics such as steel production. According to the World Steel Association, Ukraine and its European supporters alone produced twice as much steel in 2024 as did the Russians and their Belarussian allies. (And this is despite Ukrainian steel production plunging since 2021 because of Russian attacks.) Add in the U.S. and Canada, and the steel advantage rises to 3.2:1. Add in Ukraine’s supporters in East Asia and the advantage in steel rises to 5.6:1.

From this perspective, the Europeans could, if given the time to shift workers and resources from declining industries to their militaries, easily develop forces sufficient not just to repel and deter the Russians, but, if necessary, to subjugate the Russians by themselves.4 While that is still years away, there now seems to be a European consensus that rearmament is urgent, with even Germany’s notoriously tightfisted Christian Democratic/Social Union parties interested in modifying the country’s “debt brake” within the next few weeks. The U.S. would need to provide logistical and intelligence support as a backstop during the transition, but the direction of travel is clear.

The Cumulative Pressure Building on Russia’s Economy

As of this writing, the Ukrainians—by themselves—have already managed to neuter the Russian Black Sea Fleet, while the Russian Air Force is rapidly becoming depleted. The Russian Army, meanwhile, has become increasingly reliant on old men who join up to get enlistment and death bonuses to cover their children’s expenses. The Russians can, for now, produce certain weapons faster than the allies, but not at sufficient rates to meet their needs, which is why they have also been importing shells and missiles from Iran and North Korea. All of this suggests that the Russians’ ability to sustain their aggression is not only limited, but (slowly) deteriorating.

Part of the reason is that the sanctions imposed on Russia remain at least somewhat effective, despite the clear limitations that I and others have highlighted. After all, total Russian spending on imported goods, in U.S. dollars, is no higher now than it was before the war, even though international prices for many goods are higher now. (U.S. capital equipment prices are up 13% since February 2022, for example.)

On top of that, Heli Simola at the Bank of Finland found (in 2023) that Russians were paying huge premiums over market prices for certain goods because sanctions made them captive customers. Her chart below shows how this plays out in the case of Russia-China trade, and she found similar results in Russia-Turkey trade.

So despite what some propagandists might say, the sanctions remain a significant impediment to the Russian war effort. That is presumably why the Russians seem so enthusiastic about the prospect that the vise could soon be loosened.

There are other signs of stress elsewhere in the data.