Trump or No Trump, 2% Inflation Was Not Coming Any Time Soon

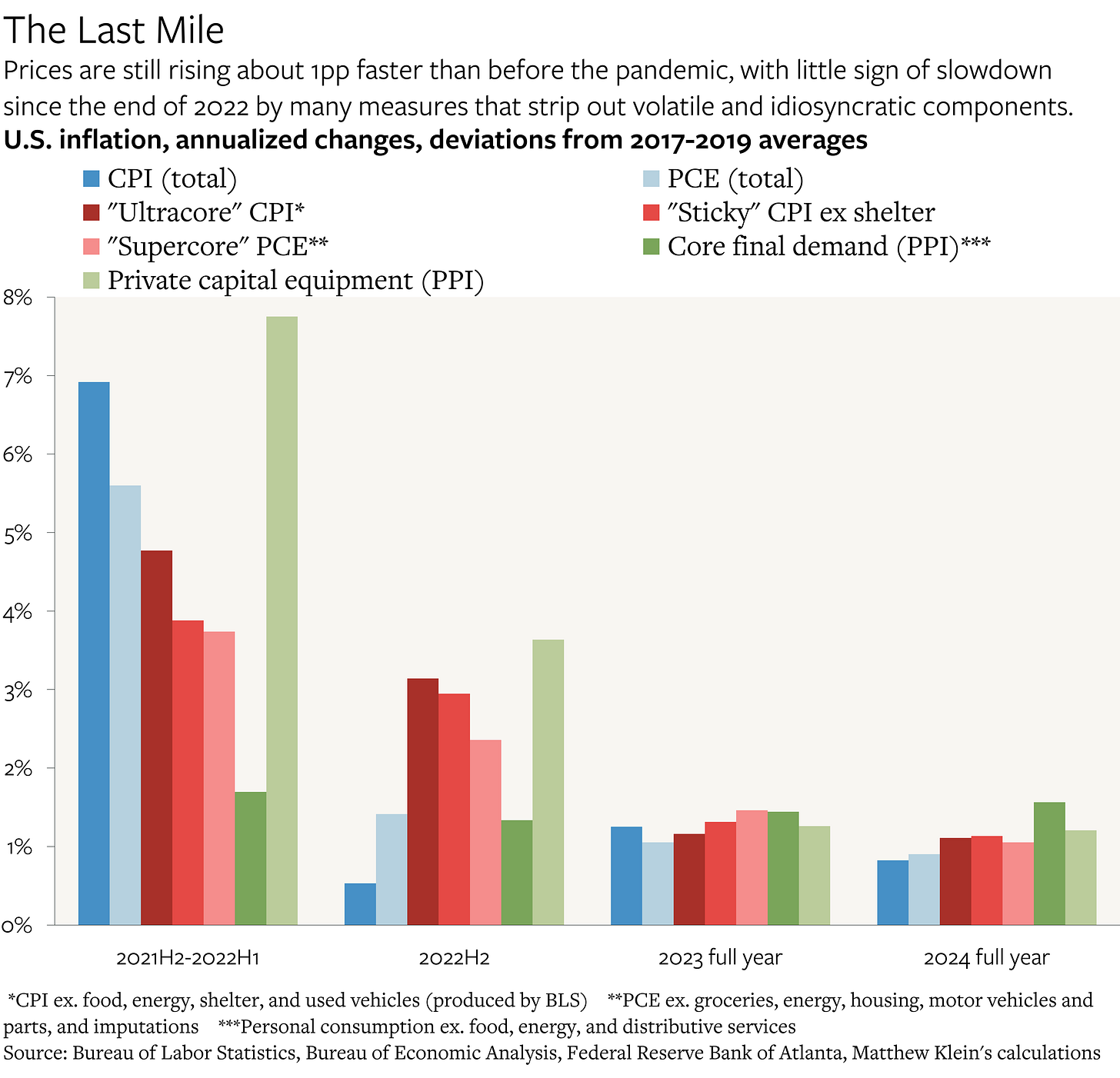

Prices were failing to decelerate even before there were concerns about tariffs and other disruptive policies thanks to robust income growth and consumer spending.

It is understandable why consumers surveyed by the University of Michigan have become more anxious about the inflation outlook over the past month. But even if there were no threats to price stability (among other things) emananting from the current administration, inflation would not be settling into the Federal Reserve’s 2% yearly target any time soon.

Inflation is what happens when the growth rate of consumer spending accelerates more than the growth rate of real goods and services volumes, and disinflation is what happens when spending growth slows more than output growth. Most of the unwelcome increase in prices since 2021 can be explained by the disruptions to production, distribution, and consumption preferences associated with the pandemic, as well as, to a much lesser extent, the Russian invasion of Ukraine—just as most of the subsequent slowdown in inflation since mid-2022 can be explained by the reversal of those disruptions.

The challenge for policymakers concerned with getting back to 2% yearly inflation1 is that there seems to have been a modest but persistent acceleration in the underlying pace of wage growth, which in turn has fed into faster nominal spending growth. (Most workers spend most of their pay, and most increases in worker pay get spent on additional goods and services.) Since the shift in the wage growth trend has not been fully matched by an acceleration in productivity growth, at least so far, inflation has been consistently faster than before the pandemic. Across a range of measures, prices are rising about 1% a year faster than in 2017-2019.

Until this month, it had seemed that nominal wage growth might finally be slowing without any downturn in the job market—and that if this trend had continued, underlying inflation might decelerate as well. But the latest data suggest that this impression was mistaken. With a few notable exceptions detailed below, the picture is increasingly that wage growth has not slowed at all and that the job market might be modestly re-accelerating. While this is clearly better for workers than the alternative, it also means that there is less wiggle room for inflation to remain contained in the face of new disruptions. Moreover, the strength of the job market may make Fed officials more willing to preempt any potential acceleration in inflation.

The Unemployment Plunge

The summer panic over the job market was unreasonable at the time, and now looks even sillier in retrospect. As of mid-January, the jobless rate was at its lowest since May 2024. Moreover, this aggregate number understates labor market health.