U.S. Job Churn Has Normalized. Wage Growth and Underlying Inflation Have Not. (Yet?)

The question is whether pay and services prices ex-housing and utilities are lagging indicators, or if there has been a persistent shift in expectations of what is reasonable.

The hot argument last summer was whether the extreme churn in the U.S. job market—which was blamed for pushing up wages, spending, and inflation—could dissipate without a downturn that would tank the economy and push millions of people out of work.

From one perspective, the debate has been settled conclusively. American employers added roughly 3 million workers (~2%) between July 2022 and August 20231 while the jobless rate has continued to bounce around its post-Korean War lows. Meanwhile, as of July 2023, the number of Americans quitting their jobs each month for better opportunities elsewhere was lower than it was before the pandemic, even though there are millions of more people in the workforce now than then.

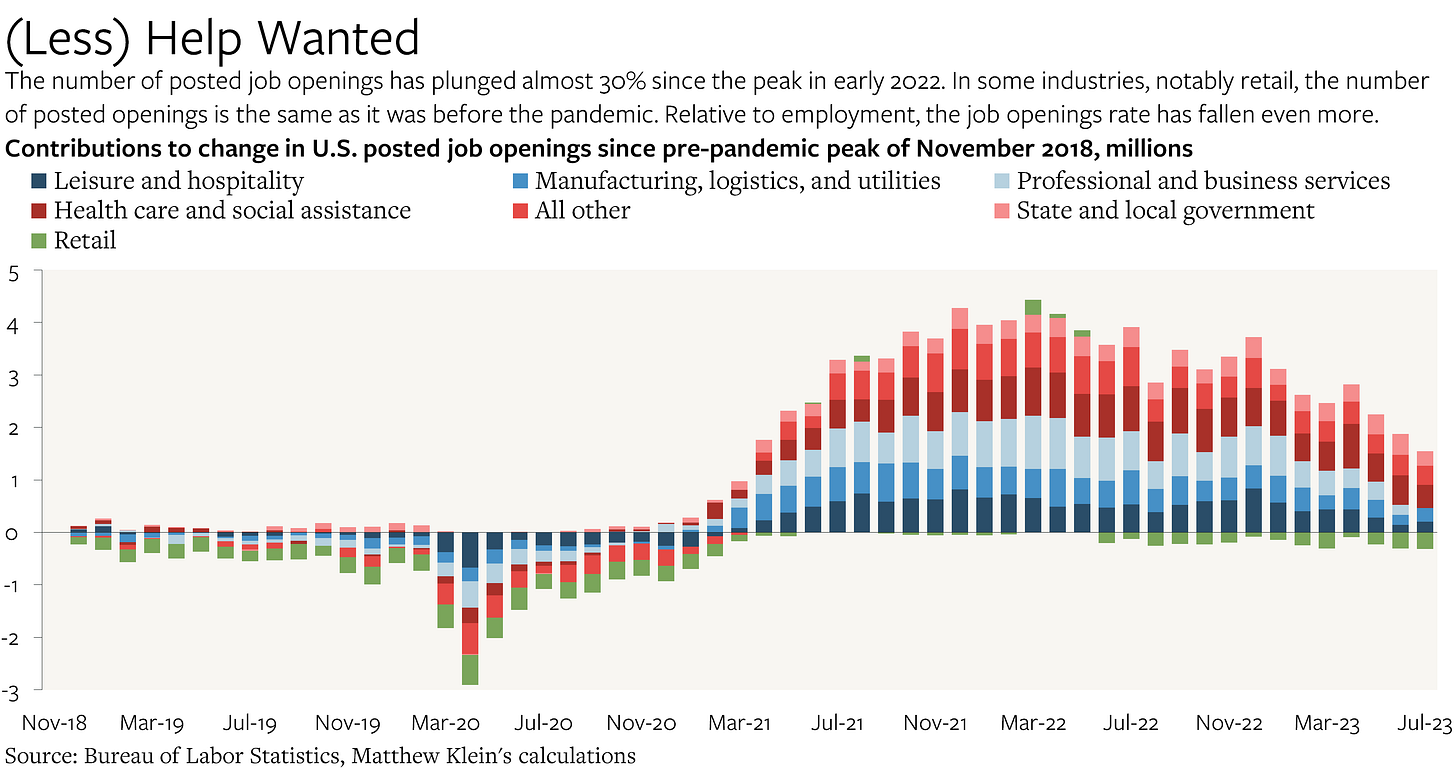

At the same time, the number of posted job openings is down almost 30% compared to the peak last spring.

Relative to total employment and the upward-sloping pre-pandemic trend, the vacancy rate in July was about as normal as can be.

Optimists such as Federal Reserve governor Christopher Waller were right and the pessimists were wrong—at least on the narrow question of whether churn could come down painlessly.

But the pessimists may yet be right about the cost of squeezing yearly inflation back to 2%.

The problem is that it is unclear whether the normalization of churn that has already occurred will be sufficient to bring wage growth—and therefore consumer spending power—back in line with what would be consistent with the Fed’s inflation target. Some measures suggest that the long-awaited deceleration has finally arrived, but others are pointing in the opposite direction. While the overall picture is more encouraging than it was a few months ago, it is still ambiguous.

Why Wages Matter for Inflation

When people get more money, they usually end up spending it. If businesses can ramp up their production of goods and services commensurately, there is no impact on prices. If not, then the extra income is fuel for inflation. Spending can be financed in many different ways, and there are many variables that affect how people choose to spend or save, but aggregate wage income tends to track consumer spending better than anything else.

Just as total spending can be decomposed into “real volumes” and “inflation”, so too can aggregate wages be decomposed into “hours worked” and “average hourly pay”. Meanwhile, the “real volumes” of goods and services produced by businesses can be thought of as the output of the hours put in by workers multiplied by the real value of their hourly labor (productivity), which in turn is a function of the equipment and knowhow at their disposal.

To oversimplify, the implication is that inflation roughly equals average hourly wage growth minus productivity growth.2 And since productivity growth tends to be relatively stable over longer time horizons, there are limits to how fast wages can persistently rise to be consistent with any given inflation target. As I explained in a previous note, the U.S. has more than nine decades of history showing a relatively tight link between worker pay increases and price growth.

Painless disinflation therefore requires (nominal) wage rises to slow without any real cost to workers. The argument that this is possible is based on a particular understanding of what caused wages to accelerate so much in 2021-2022.