Will Trump's Win (Eventually) Lead to *Lower* Long-Term Interest Rates?

The U.S. macro response to the pandemic preserved living standards better than in other economies. Voters responded more to the impact on inflation, which could affect future policymaking, and rates.

Yields on 10-year U.S. Treasury notes had been tracking the betting odds of Trump’s reelection prospects since the summer, and popped once it became clear that he would regain the presidency along with unified Republican control of Congress.

Part of the argument is that federal budget deficits are estimated to be much larger than if Congress had been divided and/or if the Democrats had won outright, thanks to the stated agenda of lower taxes1 and higher military spending. That combination could boost nominal GDP growth compared to the alternatives. There are also reasons to think that some of Trump’s signature policies, such as imposing broad-based tariffs and deporting tens of millions of people, could also be inflationary.2

While I am reluctant to question the collective wisdom of the fixed income markets, it is possible that traders are missing the potential longer-term implications of what just happened. Interest rates may end up being lower in the future than they would have been if the election had turned out differently. The question is what lesson, if any, politicians learn from how voters responded to the unusual experiences of the past 4.5 years.

People Hate Inflation

Incumbents have been losing elections across the world since the end of the pandemic.3 Even when sitting heads of government survived the elections of 2022-2024, as in India, France, and Turkey, they still endured varying amounts of voter backlash and the loss of popular support. According to John Burn-Murdoch of the Financial Times, 2024 is the first year since at least 1905 that governing parties in democracies lost vote share in every election that took place.

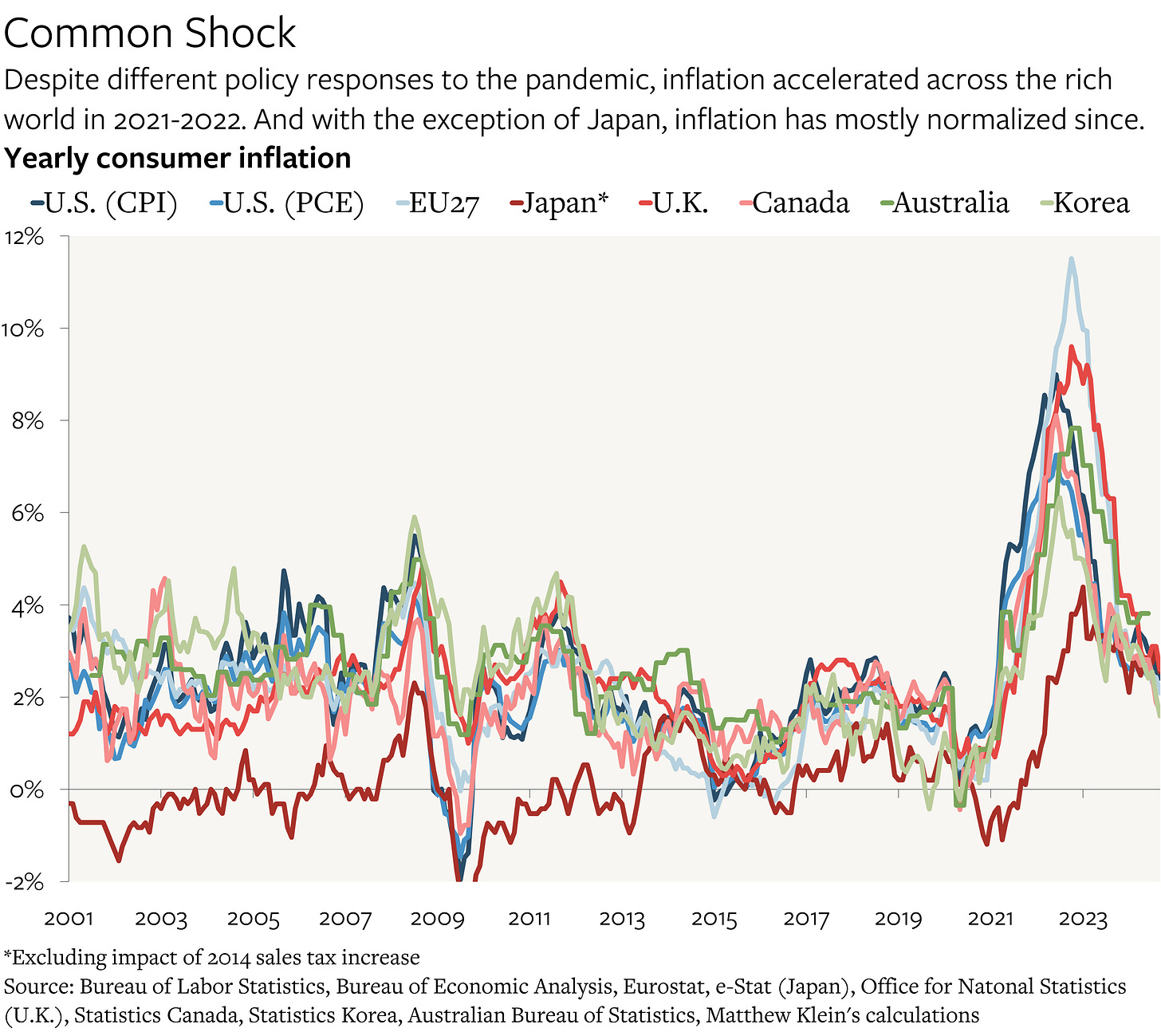

While each society is unique, it is likely that a common factor helps explain this global pattern. The most obvious possibility is that the pandemic and the burst of inflation that followed the great reopening of 2021 made life worse—and many voters blamed their specific government for this global problem.

The U.S. was no exception.